I f asked to define the career of the conceptual artist and sculptor Robert Morris (1931–2018), one inevitably begins with Minimalism, a radical art movement that elevated the simplicity of the geometric form and which Morris helped to pioneer alongside Donald Judd in the 1960s.

Beyond this, the story of the Missouri-born artist is varied: he was a prolific critic and writer, and a progenitor of land art, performance art and installation art. He worked in glass, metal, brick, peat moss, felt, among other materials. He seemingly did, or tried, it all. And yet, his conquests weren’t just visual.

In a 2010 Artforum exhibition review, writer Travis Jeppesen put it well, saying, “Robert Morris’s ultimate importance is not as an artist, but as a philosopher who happens to stage his arguments in the realm of art...Morris works in a relatively new space – or, at least, one whose canonical precedents lie in the realms of the literary and philosophical rather than the art-historical.” (August 2010).

Morris had begun his career rather typically as a painter, heavily influenced by Abstract Expressionism at the time. While living in California in the late 1950s with his first wife, the performance artist Simone Forti, he became interested in ideas of space, choreography and the body as he encountered the experimental work of John Cage, and other artists.

Moving to New York in 1960, he hit his artistic stride, creating well-received conceptual pieces; showing at the prestigious Green Gallery in 1963; and participating in the Whitney Museum’s 1964 Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Sculpture, where the critic Barbara Rose surmised, “Morris’s purpose is...to teach or to question certain very basic ideas about art, its meaning, and function...he questions the limits of art and the very activity of the artist.” (February 1965)

In those years, Morris was among a select group of artists who were seemingly anointed as arts soothsayers and, along with the likes of Donald Judd, Sol Lewitt, and several others, were “singled out by critics and curators as the chief practitioners of a new mode of three-dimensional art.” (May 1977)

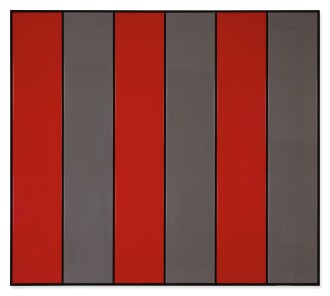

The most defining contribution of the five-decade career that followed are certainly Morris’s highly finished cube and polyhedron-form sculptures, in which he “attempted to reduce the traditional qualities of sculpture—tactility, visual incident and structure—based on extra-optical premises to a kind of total gestalt experience” which were “sensed as spatial amalgams, objects that disrupt or comment upon the space of the room” and which constitute the basis on which much of Minimalism is built (May 1966).

“Most of the readers of the magazine, viewers, people interested in art, got their first coherent sense of what was happening from Robert Morris’s essays.”

Along with these, his large-scale evocative felt sculptures were formatively influential to a group of artists (many women) working in textile or natural materials; made in dark hues, folded or cut like ribbons to hang or rest against walls, these were decidedly ceremonious, reminiscent at times of clerical vestments, and hinting at a poetic, allusory quality in Morris’ work, what a critic called “a mysterious cast” that distinguished him for his contemporaries. (August 1968).

In fact, in the 1970s, Morris would somewhat shocking turn to figurative art, confounding many of his most ardent supporters. By the 1990s, Morris had returned to abstracted forms, which he would pursue to a variety of ends for the remainder of his days.

His artistic experiments lasted late into his life. In a 2015 exhibition review Robert Pincus-Witten remarked, “It is rare to find members of Morris’s generation making such energetic work. Most, if not having already left the scene, create nothing more than the repetition of signaturized merchandise designed to resurrect the aura of discoveries long past. That has never been Morris’s way.” (December 2015).

In the totality of his career, it would be negligent not to acknowledge how deeply linked Morris was to Artforum, as a writer and critic, as well as an artist. In the late 1960s, he published his seminal "Notes on Sculpture,” a series of influential essays among other articles, and in 1974, he famously took out an advertisement in the magazine for his upcoming Castelli-Sonnabend exhibition which consisted of a photo of himself clad in S&M bondage gear (inspiration for Lynda Bengalis’s own notorious advertisement in the publication). His artwork Labyrinth, 1974, also appears on that issue's cover. As former editor Philip Leider recalls in Challenging Art: Artforum 1962-1974 (Soho Press, 2000), “Most of the readers of the magazine, viewers, people interested in art, got their first coherent sense of what was happening from Robert Morris’s essays.”

Morris was an artist of both dexterity and complexity and that has made him a challenge to pin down in the history books. In 2018, when he died at the age of 87, Artforum cut down to the essence of his career, saying simply, “Morris flouted predictability.” (November 2018)