Executed in 2006, Civil Planning is undeniably a masterwork by the New York based artist Dana Schutz. Within the densely layered compositional narrative, two young women sit under a grouping of trees, peacefully building what appears to be a rock tower and blissfully unaware of the inexplicably bizarre and grotesque oddities that surround and enclose them. Indeed, a closer look reveals that far from the bucolic haven that one might imagine, the forest is littered with dismembered body parts and other debris, and populated by orange and purple monsters that hover nearby, partially concealed by the dense foliage.

Executed at a scale that approximates life-size, Currin’s portrait of a nude young woman undressing herself provocatively confronts, and even invites, the viewer; despite the striking oddities and slight deformities of her figure, Currin’s young nude is inextricably alluring, if slightly unsettling. Revitalizing the oft-considered antiquated and obsolete genre of figurative painting, Currin’s complex and provoking compositions such as the present work intelligently reference art historical precedent whilst creating a body of portraiture that is entirely novel and contemporary in its own right, confirming portraiture’s crucial role within the vast landscape of art-making in the twenty-first century. An early champion and extensive collector of Currin’s celebrated oeuvre, David Teiger acquired Tolbrook the same year it was painted, and it has remained in his prestigious collection to date.

Setting the precedent for the Face paintings that would follow, Face No. 1 operates in the fascinating interstice between abstraction and figuration, complicating the formal correlation between the churning bands of brilliant color and the searing visage contained within them. Vibrating with a thrilling vertiginous motion, the painting evades a fixed image, instead creating a pictorial realm where physiognomy merges with the material application of paint to defiantly challenge the strict formal organization of Modernist painting.

Characterized by a disorienting, multifaceted and fragmentary perspective, Reflective Flesh presents Saville’s response to Barthes’s enigma, while continuing the tradition of such modern masters as Willem de Kooning and Pablo Picasso, all of whom addressed the female form in new and innovative ways. Saville has long been fascinated by the comparable characteristics of paint and skin and, through a meticulous process of layering, her paintings seek to explore and exploit the tactile and visceral qualities of both her medium and her subject matter. Drawing an analogy between the slow build up of paint on a canvas, and the multiple layers of identity that we construct, develop, inherit, absorb and perform over a lifetime, she writes: “I want there to be an awareness of wearing this paint body, the artifice of it – a mixture of reality and fiction. I admire the way that Cindy Sherman, in the film stills, wears these myths of femininity. You believe them but also know that it is a fictional world that she’s created.”

Monumentally scaled and dazzlingly vivid, Elephant (Violet) encapsulates the aesthetic exuberance, artistic ambition, and searing individuality which characterize the singular work of Jeff Koons. Conceived in 1995-2000, the present work is a quintessential example from the artist’s widely acclaimed Celebration series; characterized by such iconic sculptures as Balloon Dog and Hanging Heart, Koons's Celebration sculptures seek to capture the jubilant awe of youth, vividly embodied within the universal forms and images surrounding holidays, parties, and other joyful occasions.

Brazilian artist Ernesto Neto’s large-scale, immersive sculptures are at once an environment in which one can interact and at the same time evoke the body itself. "When someone decides to get inside of a piece,” says Neto, “they have another level of experience through the atmosphere created by these unexpectedly organic bodies. I believe that as living human beings we have a particular body in time, a kind of island in a cultural-physical world with skin as the border or limit. I like to work at that limit. That is my master plan. At this border is the place of happiness, the field of events where the relationship between the individuality of men and their world occur – physical, psychological and mental...I work around the space of the body, so I make art with a continuity to my own body as the producer of the work. I don’t want to make work that depicts a sensual body – I want it to be a body, exist as a body or as close to that as possible."

More from the Collection of David Teiger

T

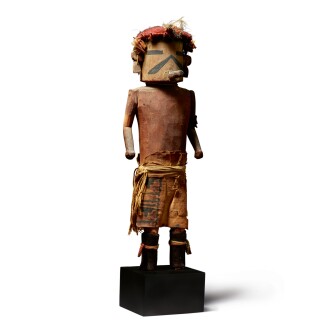

he Hopi people of the mesas of northeastern Arizona are so called as an abbreviation of the name in their own language Hopituh Shi-nu-mu, meaning “The Peaceful People” or “Peaceful Little Ones.” Carved out of dried cottonwood roots by initiated Hopi men, kachina figures – called tithu in the Hopi language – represent the different spirits that lie at the foundation of Hopi theology. These spirits, also called kachinas, act as intermediaries between the supernatural and material worlds and possess the power to bring rain to the parched desert landscape and to protect the overall well-being of Hopi villages. From December to July of each year, the Hopi believed that kachina spirits mingled among the living and held dance ceremonies during which men wearing colorful costumes embodied kachinas. The figures were presented to girls and young women as instruments of protection as well as guides for proper behavior. Far from being treated as ‘dolls’ in the Western sense, kachina figures were displayed in Hopi homes out of reverence for the spirits and as mnemonic tools.

Drawn to the wildly emotive expressions and their connection to the spiritual realm, surrealist artists André Breton and Max Ernst were renowned collectors of kachina figures. Breton displayed his collection on a wall in his Paris apartment while Ernst took up residence in Sedona, Arizona and drew both formal and narrative inspiration from the kachina pantheon and his own collection of the figures.

Kachina figures collected by the pioneer Frederick William Volz make up a significant group of those today in the Heard Museum in Phoenix, as well as the historic group from the collection of David Teiger. Volz and his brothers were among the first white men to see Meteor Crater, an enormous impact site nearby (east of present-day Flagstaff ), and worked on the excavation of the site, collecting fragments of meteorite and selling them to museums. After his brothers had each left Arizona to start families elsewhere, Fred Volz continued his trading enterprise at the Canyon Diablo Trading Post. Among his activities was the buying and selling of kachina figures made by the local Hopi peoples. Volz’s trading post at Canyon Diablo was near First Mesa, which received many influences from Zuni pueblo, and “Volz” kachina figures therefore show Zuni influence, particularly evident in their generally tall and slender form, and the articles of clothing which they wear.

Like the rest of Teiger’s collection, the works in the upcoming May auctions constitute the best of their type and speak to Teiger’s refined sense of connoisseurship. Defining excellence in a wide variety of collecting categories, Teiger was not only famously known for his relentless pursuit of perfection but also his energetic support of the arts, loaning works whenever possible and consistently donating to acquisition funds, curatorial initiatives, and world-renowned museums. This clarity of commitment to the arts will extend well into the future, as the collection is being sold to benefit Teiger Foundation, the not-for-profit organization founded in 2008 for the support of contemporary art.