H e’s known to everyone simply as “Bailey”. Friends, colleagues, family, former lovers and admirers, detractors, rivals, media, models and muses all use the mononym in resigned acknowledgment that, after all, much like Prince, Beyonce, Kramer or Ringo, there really can only be one Bailey.

Today Bailey is 84 years old. The grand old man of the lens, he’s still very much possessed of the contrarian charisma that characterised his overthrow of the staid British fashion industry, some sixty-odd years ago. I meet him in his North London mews studio, the same building he has been in for over four decades. One can imagine him here in the 1960s, zooming over the cobblestones in a Mini Cooper, perhaps some brisk jazz playing somewhere in the night, a sultry glamour-puss at his side, a Pentax slung over one shoulder.

Instead, I am greeted by a friendly assistant accompanied by an equally friendly mini-elephant, shrouded in a cloud of black fur. This is Bailey’s dog, a chow called Mortimer. Later he asks me if I have a dog and I eagerly reach for my phone, to show him a photo of my dachshund. He dismisses it, “I hate seeing pictures of dogs or children. You don’t have any children do you?”).

The Camera Never Lies | In The Studio With David Bailey

We sit at one end of the vast studio, full of photography gear of varying vintage, stacks of books (including his own, massive ‘sumo’-sized Taschen volume on a lectern), prints propped against the walls and festooned along the walls. Damien Hirst butterflies cover the far wall, where a film crew is setting up. A Bob Dylan playlist wheezes away companionably in the background (“He’s great isn’t he. Yeah, fantastic…”). Sat with a camera slung around his neck, be-scarved in Alexander McQueen, topped off with a green safari titfer Bailey beadily observing the cameras being arranged at the other end of the studio. ‘They’re taking too long,’ he grumbles. ‘I’d have had that lot set up and ready to go in 10 minutes.’ I ask how he’d do it differently and get a piercing look. ‘Well, they’ve got that camera too low, for a start…’

Now, as in the early 1960s, Bailey is focused obsessively on his work. As well as a well-received autobiography, Look Again, which came out late last year - a rags to riches tale of global glamour, 1960s London, game-changing photography and various vigorous romantic pursuits – he is working on a number of publications due out in the coming months. But it’s the show at Sotheby’s, opening in mid-March which is concerning him most now. “I’ve put in a bit of everything,” he says, as we pore over the list of images contained in the exhibition. “There’s a lot here, about 30, I chose all the ones I like…”

It is a mix of works unprecedented in a single Bailey show to date. There are paintings – or ‘over-paintings’ to be precise, a clutch of his famous portraits over the years, spattered with AbEx style splashes and daubs – still life studies of flowers and vanitas-style assemblages of skulls and keys (‘death’s everywhere innit?’) and of course, samples of the timeless portraiture for which he is still best known. There's the Queen ("She was alright, I liked her"), the Kray brothers, Lennon & McCartney, Jack Nicholson, Kate Moss (“she’s great – she’s just Kate, that’s all she has to do”) and his muses over the years, from Jean Shrimpton to his wife of almost 40 years, Catherine Dyer. “All the regulars” he guffaws.

Like so many of the young stars of art, music, film, theatre, literature and photography who sparked a cultural revolution in the early 1960s, Bailey emerged from a wartime, working-class background to storm the citadel with a sharp, aggressively Pop aesthetic, inspired by fast, new camera technology, a hungry mass media and dynamic, cash-rich post-war generation eager for imagery. In his case, success came after years of slogging away as a photographic assistant, followed by an apprenticeship with the aristocratic fashion photographer John French in 1959. Bailey struck out on his own a year later, being hesitantly snapped up by Vogue, who were alternately entranced and alarmed by his feisty personality, groundbreaking work and irreverent attitude.

Firmly rejecting the stiff plate-camera stills beloved of the elder generation of staid gentleman snappers, he shot from the hip, using new lightweight motorised 35mm cameras, prioritising a close connection with subjects that allowed them to loosen up, relax and respond to with the impish snapper's lens And the results were unprecedented. Rebellious, sexy and lyrical, his colourful personality took elements of artistic and reportage techniques, to create unique moments, dynamic situations, the click of the shutter almost an afterthought. Bailey’s confrontational compositions and high contrast tones (learned in part, to avoid oversaturating cheap newsprint) came to define the visual energy of mid-1960s London.

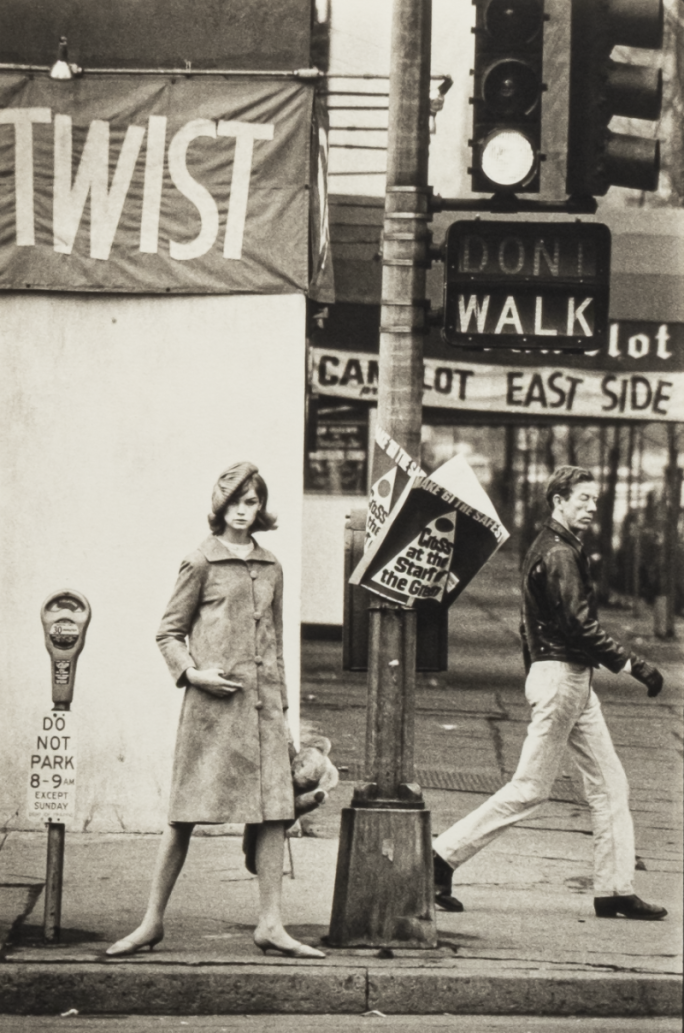

We look at the work to be featured at Sotheby’s. I ask about a famous photo he took of Rudolf Nureyev, with whom he hung out with regularly in the early 1960s, which didn’t make the cut here, but prompts the first of a succession of anecdotes. Bailey used to frequent London’s Ad Lib club, where on any one night you might find a Beatle or two, a Rolling Stone, numerous models, actors and fashion designers, Jean Shrimpton knitting serenely in the corner and on the dancefloor, Bailey himself. He wasn’t much of a lad for rock’n’roll (“I preferred jazz. Or blues.”) but he did attempt to teach Nureyev the Twist. “I didn’t really know how to do it, I’d just seen some people do it. But he was kind of stiff, I think was really difficult to go down and get up again. Ha! But I liked him, he was nice.”

He had fallen hard for elfin, 19-year old model Jean Shrimpton in 1960, whilst working as a rookie staff photographer for Vogue in London (and married to his first wife, Rosemary Bramble). In February 1962, the pair boarded a flight to New York on assignment to shoot a story, ‘Young Ideas Goes West’. This featured Jean at large, in Jaeger and Susan Small, tripping down grimy sidewalks, standing stock still, staring just off the frame, sending up Vogue’s patrician brief to appeal to a ‘young’ audience by posing with a teddy bear, tumbling almost upside down on street cars, freezing on Brooklyn Bridge (where Jean would actually faint from the cold), and inhabiting the city, responding to Bailey’s spontaneous, idiosyncratic ideas - and more than a few lucky accidents.

The results, when published later in the year stunned the fashion world. No-one had taken photographs like this before. Bailey’s elegant, casual style heralded a new era in fashion photography. And as he acknowledges today, he was responding to the zeitgeist. “I don’t know what happened, but I think it was that we had all come of age, to be honest, we were all old enough to do it but young enough to be new. I don’t know, before it seemed that working class people didn’t get to do things like that.”

Things were changing fast, in 1962. Bob Dylan debuted Blowing in the Wind in a New York folk club, James Bond made his first film outing in Dr No, Anthony Burgess published A Clockwork Orange, the BBC launched the unprecedentedly satirical show That Was The Week That Was, Andy Warhol premiered his Campbells’ Soup Cans in Los Angeles, LED lights were invented, Mandela was jailed, The Beatles released their first single, Love Me Do, The Rolling Stones formed – and as Bailey modestly states in his autobiography, his New York shoot, ‘changed everything in fashion photography’. And Bailey’s confrontational compositions and high contrast tones (learned in part, to avoid oversaturating cheap newsprint) came to define the visual energy of mid-1960s London.

Portraiture beckoned. With a minimalist aesthetic, Bailey’s lens framed a series of famous and infamous faces of the 60s, from Jean Shrimpton to the Kray brothers, Lennon and McCartney to Michael Caine. Each subject was shot in high-contrast, brutal monochrome, a bracing corrective to the era’s garish style, freezing identities and public perceptions that remain to this day.

Bailey’s success as a portraitist hinged on his uncanny ability to connect and form an instant rapport with his subjects. “I can meet someone and know immediately how I would like to frame them. I’ve framed you already, soon as I saw you” he informs me, to my slight alarm. He has patiently explained this alchemical aspect to his practise many times in the past. When journalists ask, for instance, how he managed to take that portrait of Her Majesty caught mid-guffaw, he relates how he took the shot immediately after he’d told her he had “swearing Tourette’s”. With villainous twins, the Krays, he has often spoken of the sleepless, terrifying fortnight he spent shadowing them across their underworld empire, from East London into the heart of the West End, witnessing outbursts of violence, madness (a man vanished - presumed beaten to death by Ron Kray - for pestering Bailey in a pub one night) and the pathological neediness that drove the murderous pair.

Other East End icons were more agreeable. “Michael Caine told me, that before I photographed him, he was an actor,” chuckles Bailey, gazing at the iconic photo of a bespectacled Caine looming menacingly into the lens. “But after that photo, he was a movie star”.

And Bailey himself was a cinematic inspiration – sort of. In 1965, the filmmaker Michaelangelo Antonioni began work on Blow Up, a ‘mod masterpiece’ set in the world of an iconoclastic photographer, played by David Hemmings and clearly influenced by Bailey. The man himself is not so impressed, though. “I thought, first of all, they should have used Terry Stamp for that part, he was working class. David Hemmings was too middle class. I thought the film was OK, not a great film. I think he was based more on John Cowan really, or Terry Donovan. He was that class, same middle class kind of guy. He was miscast anyway but who am I to judge… The film sold thousands of Nikons and Pentaxes and had people twirling around taking snaps.”

As the Sixties dissolved into the Seventies, Bailey epitomised the rise of the international jet set. Diversification into various fields saw the photographer venturing into creating album covers, making commercials, documentaries and the odd movie. He launched a gossip magazine which, in Look Again, he rates as being a British version of Interview, creating paparazzi culture. And he continued to shoot fashion, but now he’d do portraits of designers like YSL and Blahnik, as well as the models. Global travel, books documenting trips to far-flung locales. A hectic social and romantic life, dating or sometimes marrying, glamorous ladies such Catherine Deneuve, Sue Murray, Marie Helvin, Anjelica Huston and Penelope Tree - before settling down with his wife Catherine Dyer, in the early 1980s, with whom he has three children.

Since the publication of his autobiography Look Again in 2021, all the above and much much more has become public record. But any notion that its release marks a decline into a retirement of cantankerous anecdotage is very much mistaken. From what I can see, in his mews studio, numerous projects are moving ahead at a brisk clip, including preparing Bailey’s Parade at Sotheby’s, release of five (five!) new books, including a much-anticipated update of his legendary 1960s box of images, Pin-Ups. The exhibition at Sotheby’s brings together for the first time, not only a selection of Bailey’s portraiture over the years, but also a set of Vanitas flower portraits and a few of his rarely-exhibited overpainted works – classic portraits augmented with Expressionist slaps, drips and strokes of paint, a vibrant commentary from the present-day over faces from the past. These works present a lesser-known side to Bailey, who has been a keen painter and sculptor for many years and here, applies that sense of structure and colour to the works that remain dramatic moments in time, frozen in eternity.