Ming style furniture combines advanced engineering with minimalist aesthetic. With simple lines and curves that favour grace over extravagance, the furniture showcases an ingenious joinery system that employs a seamless mitre, mortise and tenon construction. This tradition embodies the technical know-how of Ming artisans, the ethos of literati scholars and the elegance of an extraordinary era.

The Song dynasty saw an unprecedented development and aesthetic appreciation of Chinese furniture, which continued to flourish over the years, reaching new heights during the Ming dynasty. Famous ancient paintings offer us a glimpse of a subtle shift; Song literati are typically portrayed seated or standing with a straight back and a composed manner, while Ming dynasty scholars, in contrast, are depicted in relaxed postures, appearing to enjoy a vibrant lifestyle. This is all deeply connected to the political and cultural ideologies of their respective times. Ming scholar Gao Lian’s (1573-1620) Zunsheng Bajian (Eight Discourses on the Art of Living) focuses the seventh volume of the work on the topic of home living, highlighting furniture’s role as a means to fostering a sound environment for both body and soul.

120.5 by 62.7 by h. 87.2 cm, 47½ by 24¾ by h. 34¼ in.

Estimate: 2,000,000 - 3,000,000 HKD

This elegant pair of tables exemplifies the ingenuity of Ming carpenters, who developed sophisticated joinery techniques to create tables that could support heavy loads with the minimum use of material. The restrained elegance of these tables is achieved through their simianping, or "four corner’s flush," construction where the legs are set flush to the table top, and joined by carved spandrels that add stability and strength. This design, which first emerged in the Song dynasty (960-1279), was considered one of the most attractive furniture designs in the Ming period.

Narrow rectangular tables with legs at the four corners (zhuo) were some of the most versatile types of furniture, ubiquitous in every Ming households. Woodblock printed illustrations depicts them being used in numerous different ways, according to different needs and contexts. They are commonly depicted in bedrooms and used as writing desks or for informal meals, against the side walls of reception halls where flowers or other tasteful objects were displayed, as well as for formal dining.

104.5 by 64.4 by h. 86.7 cm, 41⅛ by 25⅜ by h. 34⅛ in.

Estimate: 1,200,000 - 1,800,000 HKD

This exquisite table is special for its finely carved aprons and spandrels, which include a lively depiction of phoenix among clouds flanking the sun. It belongs to a highly unusual group of profusely decorated side tables, whose upper part resembles a kang table – low tables used on the heated kang. The well-known Chinese furniture scholar Wang Shixiang thus refers to them as ai zhuo zhan tui shi or "low table with extended legs." The abundance of carved decoration on these tables represents a clear departure from the clean and sober aesthetics more commonly associated with 17th century furniture, and demonstrates the co-existence of different furniture styles in this period.

84.8 by 46 by h. 112.5 cm, 33⅜ by 18⅛ by h. 44¼ in.

Estimate: 1,500,000 - 2,000,000 HKD

The panelled doors of this cabinet open to reveal fourteen small drawers of different sizes. Square-corner cabinets with multiple drawers are generally described as apothecary cabinets and used for storing herbs and medicines, but could have been used to store and sort a variety of objects, from documents to writing materials, accessories and treasured objects. The Ming dynasty intellectual and theorist on interior design Li Yu (1611-1680?), in his Xian Qing Ou Ji (Miscellaneous Notes on Times of Leisure) from 1671, discusses the usefulness of drawers and describes a multi-drawer cabinet designed for scholars after pharmacists’ "hundred-eye cabinet" (bai yan chu).

267 by 50 by h. 89 cm, 105⅛ by 19¾ by h. 35 in.

Estimate: 3,500,000 - 4,500,000 HKD

Long and narrow rectangular tables with upturned flanges were popular in wealthy households of the Ming (1368- 1644) and Qing dynasties. The present example is however particularly special for delicately carved panels between the legs, and the attractive grain pattern of the huanghuali boards set into the top frame. Placed against the south wall of the reception hall, where important male visitors were greeted, they were used for the display of a few tasteful objects, such as fantastic rocks, seasonal flowers or a treasured antique. Tables of this type with the panels between the legs carved with ruyi heads appear often on contemporary printed books and paintings, such as in the illustration of Chapter 7 of a Chongzhen period edition of Jin Ping Mei (The Plum in the Golden Vase). The origins of this type of rectangular table may have a design derived from altar tables made from as early as the Eastern Zhou dynasty (771-256 BC) (Selected articles from "Orientations" 1984-1999, Hong Kong). These early tables with upturned ends are depicted on archaic bronzes from this period, however the use of upturned flanges, however, appears to have disappeared prior to the Ming period, when these long rectangular tables gained popularity. The flanges served as a reference to China’s illustrious past, which also increases the table commanding presence within the room.

226 by 156.2 by h. 226 cm, 89 by 61½ by h. 89 in.

Estimate: 20,000,000 - 30,000,000 HKD

Sumptuously carved in openwork with sinuous chilong writhing around auspicious motifs, this magnificent canopy bed is a display of 17th century aristocratic splendour. Employed in the inner quarters by both men and women, beds were the focal point of the household, and six-post canopy beds were most luxurious and impressive type of bed that one could own.

While used by both men and women, canopy beds were the most used pieces of furniture in women’s apartments. Households of the 17th century that adhered to Confucian norms confined women to the inner courtyards of a family compound, away from the front of the house where important male visitors were received and official functions took place. Bedrooms were informal rooms where women spent many of their waking hours, thus their furnishing, especially the bed, were important status symbols, indicating their position within the family. During daytime, canopy beds were used as seats for informal leisure: a long table and footstool were placed in front of the bed for comfortably reading or eating. A few stools and chairs could be arranged around the bed for an informal gathering. At night, curtains were hung within the bed frame to protect from drafts, mosquitoes as well as prying eyes.

Most importantly, beds were the place where children were conceived and their decoration is often filled with auspicious omens that reflect this function. On this bed sinuous chilong, young hornless dragons, dominate the design and represent the aspiration of conceiving meritorious sons. Auspicious clouds, rocks and lingzhi, and shou (longevity) characters were believed to bring blessings and good luck to those within. Designs on beds could also be indicative of a person’s social status.

126.5 by 63 by h. 251 cm, 50 by 24¾ by h. 98¾ in.

Estimate: 5,000,000 - 7,000,000 HKD

These massive cabinets are the largest type of furniture produced by Ming cabinet makers. Composed of a wide square-corner cabinet and a smaller chest that was placed on top, they combine functionality, durability, elegance and simplicity, characteristics that define classical Chinese furniture. The masterful craftsmanship in the present lot with the decoration of the turbulent waves on jagged rocks on the sides in particular suggests an imperial association for the cabinets. Compound cabinets were the piece-of-resistance in the home of wealthy families. Displayed in inner reception halls or kept in the women private quarters, their sheer size and angular silhouette were designed to create an impression of awe.

Chinese garments were never hung but folded into flat rectangles and stacked in cabinets, and the large size of these cabinets made them ideal for storing garments or other large items. The upper chests, which were less accessible and often required a ladder to reach them, were used for storing accessories or garments that were needed less frequently. Large chests were part of a bride’s dowry, and the Ming dynasty novel Jin Ping Mei (Plum in the Golden Vase), reveals that lady’s fur coats were kept in large cabinets that could be locked.

each 61 by 3 by h. 306 cm, 24 by 1¼ by h. 120½ in. overall width 729 cm, 287 in.

Estimate: 5,000,000 - 7,000,000 HKD

This magnificent screen would have stood in a grand hall to create a striking backdrop for a formal reception or official event. Deftly carved with an intricate motif of chilong and auspicious characters, this screen demonstrates the bold creativity of woodcarvers working in the 17th century. The folding screen served multiple functions: it divided a room concealing areas and objects that were not supposed to be displayed, and provided a hiding place for ladies, who could peek at important visitors through the openwork carving. When mounted with paintings by a famous artist or lines from a favourite poem, both of which were viewed and read from right to left as a traditional Chinese book, it heightened their importance and showcased the sophisticated taste of the master of the house. Such monumental screens were made only for the wealthiest aristocratic families, and are thus very rare.

Multi-panelled screens have a long history in China, developing from single-panelled screens made as early as the Warring States period (475-221 BC) and becoming popular from the Northern Wei dynasty (AD 386-534). These early screens, which were relatively short, framed a platform where high-ranking individuals sat or enclosed a canopy bed to provide privacy. Screens gradually become larger and the most impressive examples were made in the Ming and Qing dynasties. While they often appear on woodblock printed books of the period, extant examples are rare.

38.6 by 27.7 by h. 79 cm, 15⅛ by 11 by h. 31⅛ in.

Estimate: 300,000 - 500,000 HKD

This waisted incense stand possesses a curvilinear apron decorated with carvings of tendrils, and four cabriole legs terminating in an upward turning leopard foot motif set to a base. Its overall form is elegant, defined by flowing curves and smooth lines.

“Wealthy families may put [the incense stand] in the grand hall, with an incense burner placed on top, or it may be found in the central hall for the ladies to worship the gods and seek blessing of great needlework skills. Incense stands are also seen in Taoist and Buddhist temples, and both incense burners and ritual objects are placed on the stands.”

In a poem, Southern Song dynasty literatus Lu You wrote on the pleasure of reading while burning incense, a luxury he enjoyed despite an otherwise simple lifestyle due to his modest salary as a government official. In famous paintings such as Ting Qin Tu (Listening to the Qin) by Emperor Huizong of Song, fragrant incense provided an elegant companion to the sound of the qin (a music instrument), while in Ting Ruan Tu (Listening to the Ruan), flower appreciation and tea drinking was accompanied by incense burning (ruan being another music instrument). These examples illustrate the essential role incense played as part of literati aesthetics and lifestyle.

141 by 51.8 by h. 193 cm, 55½ by 20¾ by h. 76 in.

Estimate: 4,000,000 - 6,000,000 HKD

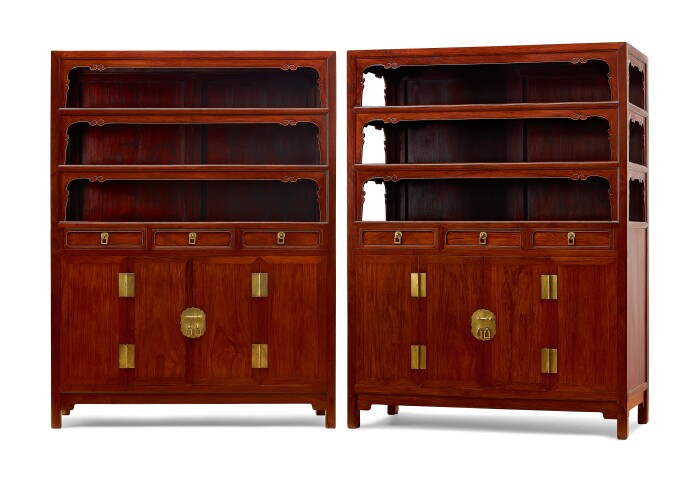

Striking for their imposing size, this pair of cabinets with open shelves demonstrate the exceptional skill of 17th century furniture makers in their ability to take full advantage of the vivid colours and patterns of precious hardwood. This type of cabinets with multiple open shelves, known as Wanligui (Wanli period cabinets), is highly unusual.

First appearing in the mid- to late Ming dynasty, they were generally kept in the scholar’s studio, where their arrangement either side by side or on opposite walls, created a visual symmetry sought after in Chinese room design. The top shelves were used for storing books and scrolls as well as treasured antiques, while writing implements, such as brushes and ink, were kept inside the drawers. The sturdier and enclosed lower were on the other hand, used for storing more fragile objects or tea utensils that could be brought out in the presence of guests.

Referred to as lianggegui by modern cabinet makers, this type of bookshelf seldom appears on contemporary woodblock printed books, attesting to its rarity. The display and storage of books in the scholar’s studio was of great importance as it was indicative of the level of education and cultural refinement of the master of the house.

212 by 108.5 by h. 50 cm, 83½ by 42¾ by h. 19⅝ in.

Estimate: 1,800,000 - 2,200,000 HKD

Ta daybeds are among the oldest type of furniture made in China. Popular since the Han dynasty, when they elevated high-ranking individuals, by the Ming period these raised rectangular platforms were used both in scholar’s studios and in sleeping quarters. More commonly made to accommodate only one person, the impressive proportions of the present example would have made it an ideal double-bed at night and a practical living platform during the day. The rounded members of this daybed and its stretchers, which encircle the legs and create a double-moulded design, imitate bamboo furniture construction. Bamboo had long proved a popular furniture medium: not only was this wood traditionally associated with virtuous qualities in a scholar, its flexibility and natural roundness allowed craftsmen to create furniture that was comfortable, light and attractive. Ming dynasty cabinet-makers recreated these qualities in precious hardwood through a laborious process of carving and lathing. Daybeds of such large dimensions are unusual, and those carved to simulate bamboo are seldom known.