I n March, 2018, Olivier Valmier, Asian Expert at Sotheby's Paris, received a phone call from a woman who had recently lost her husband and was clearing her house to move to the countryside. She talked him through a few objects that originated in Asia – a dragon robe, a censer, a mirror in a lacquer box and a vase painted with animals – but explained she wouldn't be able to send photographs.

On hearing that the censer had an accompanying invoice from the 1867 Universal Exhibition in Paris, Valmier's interest was piqued. He asked her to bring the objects in to show him but she insisted it was too far to travel and that she might waste his time. Eventually she agreed to bring one object for inspection and Valmier chose the vase.

She arrived at Valmier's office with the vase wrapped in newspaper, nestled in an old shoebox and wrapped in a plastic bag. Stunned, Valmier and his colleagues carefully examined the porcelain piece. If it was a good quality copy from the late 19th or early 20th century, it could be worth €100,000.

“It was as if we had just discovered a Caravaggio.”

But this was the real deal: an incredibly rare 18th century vase produced by the famed Jingdezhen workshops for the court of the Qianlong Emperor, in perfect condition. In Valmier’s words: “It was as if we had just discovered a Caravaggio.”

Sell with Sotheby's

Wonder how much your art or object might be worth and how to sell it? See how easy it is to sell with Sotheby’s. Our specialists will review your submission at no cost and provide preliminary estimates for items that can be included in one of our sales channels in 5 to 7 business days.

Start Selling

Read the Full Story

H istory is scattered with tantalising clues to treasures that we can only imagine today. Seemingly lost forever are the sacred Ark of the Covenant, the prized 16-century Honjo Masamune sword and the vast majority of the works of the Greek poet, Sappho.

Whether stolen, destroyed, overlooked or simply forgotten, even the most prized objects and artworks can slip through the cracks. Famously, several of the fifty “Romanov” Fabergé eggs made for the Russian imperial family were never recovered after the Russian revolution and deaths of Tsar Nicholas II and his family. The infamous Florentine Diamond, that once belonged to the Medici family, vanished in Switzerland some time after World War One and its whereabouts are a mystery to this day. Jewels of the Order of St Patrick, known as “the crown jewels of Ireland” were stolen from Dublin Castle in 1907 and have never been found.

If we are lucky, we might have descriptions of these items recorded in official documents or inventories, or perhaps their beauty and worth has simply passed into legend. Very occasionally we have illustrations, copies or even photographs to placate us.

Sometimes, though, treasures are not lost but simply hidden out of sight.

The Lost Imperial Chinese Vase Found in a French Attic

In March, 2018, Olivier Valmier, Asian Expert at Sotheby's Paris, received a phone call from a woman who had recently lost her husband and was clearing her house to move to the countryside. She talked him through a few objects that originated in Asia – a dragon robe, a censer, a mirror in a lacquer box and a vase painted with animals – but explained she wouldn't be able to send photographs.

On hearing that the censer had an accompanying invoice from the 1867 Universal Exhibition in Paris, Valmier's interest was piqued. He asked her to bring the objects in to show him but she insisted it was too far to travel and that she might waste his time. Eventually she agreed to bring one object for inspection and Valmier chose the vase.

Delayed by train strikes, the woman arrived on her own at Valmier's office. She had brought the vase wrapped in crumpled newspaper, nestled in an old shoebox and wrapped in a plastic bag. Stunned, Valmier and his colleagues carefully examined the porcelain piece. If it was a good quality copy from the late 19th or early 20th century, it could be worth €100,000.

But this was the real deal: an incredibly rare 18th century vase produced by the famed Jingdezhen workshops for the court of the Qianlong Emperor. It was in perfect condition. In Valmier’s words: “It was as if we had just discovered a Caravaggio.”

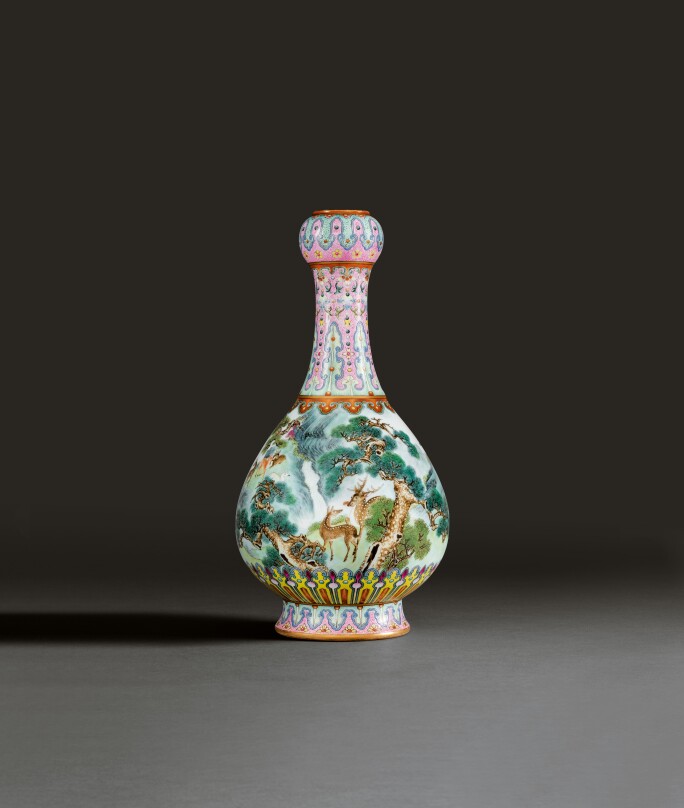

The vase belonged to the Famille-rose or “yangcai” type of Chinese porcelain, known for its vibrant colours and expert level of craftsmanship. The highly complex painting was extremely labour-intensive to achieve a luxurious and multi-layered effect. This particular vase features an extraordinary handscroll scene with meticulous detail of deer, cranes, mountains and forests. This kind of auspicious symbolism reflected the benevolent governance of the Emperor: the paradisiacal landscape is likely a rendering of the lush vegetation of one of the Imperial pleasure gardens.

"it was initially predicted that the vase was worth around €700,000, but when it went under the hammer in Paris, it sold for €16,182,800 – a new record"

This type of porcelain was produced in extremely limited quantities and other remaining examples are mostly housed in museums around the world including the only comparable vase, of similar size and shape (albeit with different imagery), which belongs to the Guimet museum in Paris.

Sotheby’s initially predicted that the vase was worth around €700,000, but after an intense twenty minute bidding battle when it went under the hammer in Paris, it sold for an unprecedented €16,182,800 – a new record for any Chinese porcelain sold in France at auction.

The royal connection to Emperor Qianlong gave the vase even greater significance, and the extremely rare nature of the artwork of the vase enabled Sotheby’s experts to make direct links with the 18th century Imperial inventory which lists just two pairs of vases with designs matching that of the newly discovered piece. One pair was commissioned in 1765 for delivery to one of the “Buddha Halls”, areas for the Emperor’s private worship, and the other ordered as a birthday gift in 1769.

So where had such a precious and extraordinary artefact been hiding before it landed, in a shoebox, at Sotheby’s Paris? In fact, it had been bequeathed to the present owners by grandparents who had in turn acquired it in the will of an uncle who had died in 1947.

Further investigation revealed that this uncle evidently had a passion for Asian art, with several of the other Chinese and Japanese objects in the collection also being sold by Sotheby's. How he came into possession of the vase is a mystery although the family records did include more details that an ancestor received the Satsuma censer as a wedding gift.

Ironically the unsuspecting owners did not particularly care for the vase – it was "too pink" for their taste – hence how it came to reside in a box in the attic where it easily could have remained hidden for three more generations. For Valmier, it was a "unique" experience to be a part of the discovery that he also describes as a "human adventure".

It may come down to luck that such a precious item was not broken or damaged in the years it was hidden from view but thankfully, that keen-eyed uncle spotted a treasure that clearly brought him happiness. Now it has resurfaced for the world to enjoy, its days in a shoebox are surely over.