T he history of clothing and textiles dates as far back as 100,000 – 500,000 years ago. It’s difficult to arrive at a more precise time period, because textiles are notoriously fragile to the environment, as they naturally disintegrate over time. But we do know that weaving and later, knitting, sewing, and embroidery were all relegated to “women’s work” across cultures. This was so, in large part because childrearing was considered the main concern of a woman’s role in the family, and her additional contribution had to be work that she could perform while simultaneously taking care of children – in other words, work that was repetitive, that didn’t require too much focused attention, and that she could easily return to amidst constant interruption. Because of its gendered assignment, coupled with the fact that cloth-making was such a functional skill, the idea of textiles as an art medium and art form didn’t take hold until recently, despite its millennia of history. Anni Albers, one of the most influential textile artists of the twentieth century, was the first weaver to have a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art; the year was 1949.

“Along with cave paintings, threads were among the earliest transmitters of meaning.”

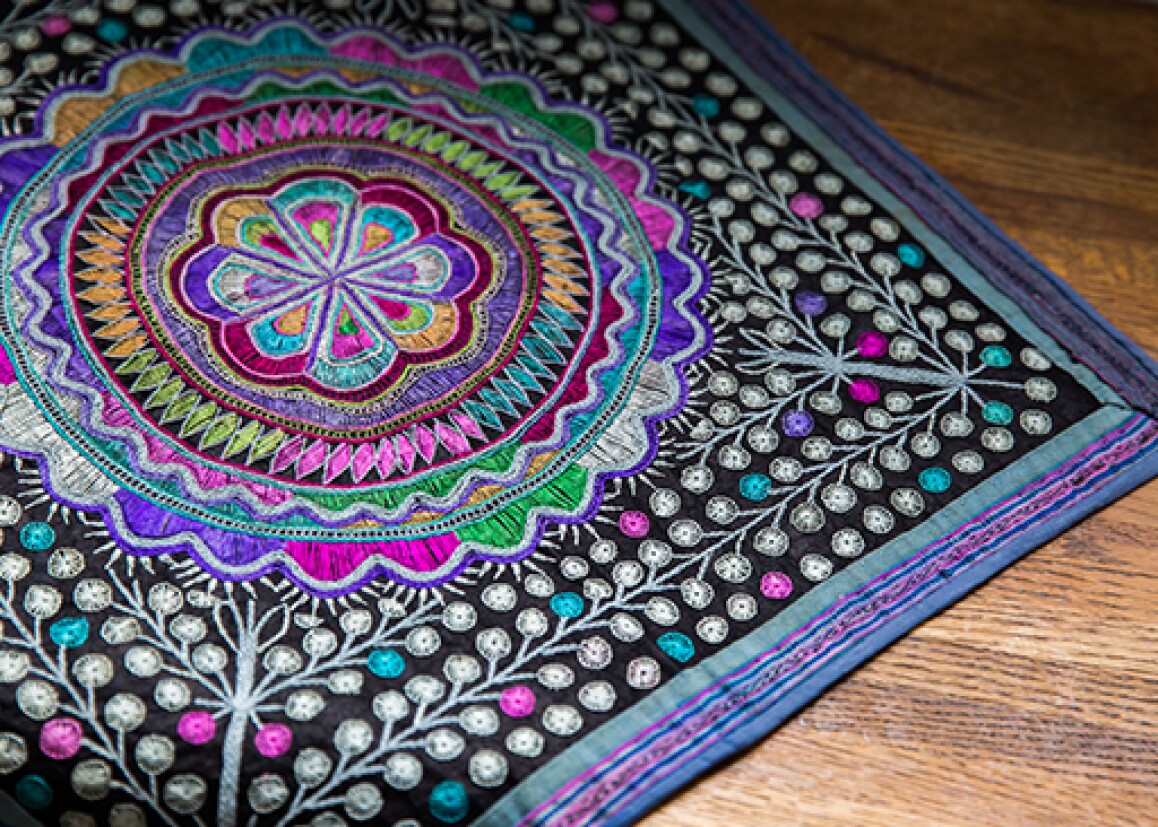

Evidence suggests that from as early as the Neolithic period (c. 4000 BCE) women began to spend extra time on cloth-making to add designs and embellishments, producing works that transcended mere function. Like language, textile can relay information – the specific colors, techniques, and symbols adorning textiles can denote social rank, record history and folktales, all the while act as a kind of protective covering. This is especially true for cultures that don’t have a written language, such as the indigenous peoples and ethnic minority tribes of Asia. These cultures tend to have incredibly rich forms of expressions through fiber arts.

In the Miao tribe, for example, young girls are taught the techniques of weaving, cloth-dyeing, and embroidery from the age of four. The poetic irony for this culture, which doesn’t have its own written language, is that “illiteracy” and not attending school had, in turn, helped preserve the art of writing and recording through the techniques of embroidery. In fact, embroidery in Miao culture is referred to as nu shu, “women’s script.” Along with a rich oral tradition, weaving and embroidery are the medium through which histories, origin stories, and observations of the natural and spiritual world are depicted and passed down to the next generation.

“Ethnographic parallels worldwide show that enormous time is often put into ‘simply’ decorating people and things with efficacious symbols believed to promote life, prosperity, and safety…Thus ‘art’ is at once pleasing and thoroughly functional – a double winner.”

And yet, perhaps because of the practicality of textiles – as clothing, bedding, floor and wall coverings – they were rarely considered art even if highly decorative. Furthermore, weaving, sewing, and embroidery had once been technical skills expected of all girls, so the perceived quotidian nature of these skills downgraded its products into necessities and, at best, crafts.

When we consider what makes something art, there is a sense that it is a work that exists outside the realm of the practical. One cannot argue, of course, with the function of art in defining culture, in being a necessary medium through which human emotions and the human condition are translated. However, as Albers so astutely writes, “usefulness does not prevent a thing, anything, from being art. We must conclude, then, that it is the thoughtfulness and care and sensitivity in regard to form that makes a house turn into art, and that it is this degree of thoughtfulness, care, and sensitivity that we should try to attain. Culture, surely, is measured by art, which sets the standard of quality toward which broad production slowly moves or should move.”

In this light, when we consider the textiles produced by those not accorded the status of artist, and the amount time and design that goes into each piece, are they not works of art filled with totems of meaning, protection, incredible skill, and above all, beauty?