Rediscovered after nearly a century, two scrolls from the early Qianlong reign were originally part of a set of ten paintings the poetry Fan Chengda and painted by Prince Shen (Yunxi) and others. Beyond their exceptional rarity, these important works represent fantastic examples of literati art and offer a glimpse into the carefully observed holiday practices of the Qing imperial court.

S ince the reign of Shunzhi, the Qing dynasty emperors consciously assimilated aspects of Han culture into the Manchu way of life from the imperial household down to the common folk. Adopting shared customs may reflect a type of administrative savvy on the part of the Manchu rulers even as they continued to hold their distinct identity in imperial traditions and ceremonies. Thus during observed Han festivals, especially during New Year, there was great importance placed on decorating the palace with paintings alluding to the relevant customs or conveying good wishes.

Sometimes the emperors would paint these works themselves, or other times the artist would be the members of the imperial family, prominent courtiers or court painters. In some of these paintings, fruit, flowers or food are juxtaposed to connote blessings. Other style are hybrids of portrait and ruled-line painting, which show festive scenes of imperial household.

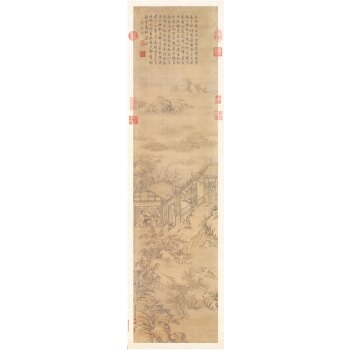

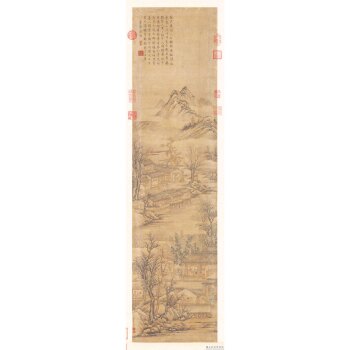

During the early reign of the Qianlong Emperor, there was a set of ten paintings ("The Ten Paintings") inspired by Fan Chengda’s poetry “Ten Ballads on Fields and Villages in the Twelfth Month” and painted by Prince Shen (Yunxi) and others. Of the original ten scrolls, one is now lost, seven are in the collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei, and the remaining two ("The Two Scrolls" ) will be up for auction at Sotheby's Fine Classical Chinese Paintings sale (19 April | Hong Kong). Shen Yuan’s Poetic Idea of “Song on the Lantern Fair” and Li Shizhuo's Poetic Idea of “Song on the Headcount Congee” are both fantastic examples of literati art and their survival is testament to their importance.

The Ten Paintings are described in an entry in the third edition of the Shiqu Catalogue of Imperial Collection of Painting and Calligraphy, as ink and colour on rice paper with dimensions of about 112.8 x 28.8 cm. The catalogue lists the paintings in the following order:

- 1. Prince Shen

- 2. Shen Yuan

- 3. Zhou Kun

- 4. Li Shizhuo

- 5. Ding Guanpeng

- 6. Zhang Hao

- 7. Chen Shijun

- 8. Dong Bangda

- 9. Cao Kuiyin

- 10. Zhang Ruocheng

-

Prince ShenPoetic Idea of “Song on Hulling Rice” (Lost)

Prince ShenPoetic Idea of “Song on Hulling Rice” (Lost) -

Shen YuanPoetic Idea of “Song on the Lantern Fair”,

Shen YuanPoetic Idea of “Song on the Lantern Fair”, -

Zhou KunPoetic Idea of “Sending off the Kitchen God”

Zhou KunPoetic Idea of “Sending off the Kitchen God” -

Li ShizhuoPoetic Idea of “Song on the Headcount Congee”

Li ShizhuoPoetic Idea of “Song on the Headcount Congee” -

Ding GuanpengPoetic Idea of “Song on Cracking Bamboo”

Ding GuanpengPoetic Idea of “Song on Cracking Bamboo” -

Zhang HaoPoetic Idea of “Song on Braziers Alight”

Zhang HaoPoetic Idea of “Song on Braziers Alight” -

Chen ShijunPoetic Idea of “Song on Lighting up the Fields”,

Chen ShijunPoetic Idea of “Song on Lighting up the Fields”, -

Dong BangdaPoetic Idea of “Bidding Farewell to the Old Year”

Dong BangdaPoetic Idea of “Bidding Farewell to the Old Year” -

Cao KuiyinPoetic Idea of “Selling off Idiocy”

Cao KuiyinPoetic Idea of “Selling off Idiocy” -

Zhang RuochengPoetic Idea of “Beating Dung Piles”

Zhang RuochengPoetic Idea of “Beating Dung Piles”

"Except for the first by Prince Shen, which is lost, and the second and the fourth, which are under discussion in this article, the set is housed in the Palace Museum, Taipei."

As described in the imperial catalogue, each of the painting bears a signature inscription that is preceded by the Chinese character for “your servant” and is inscribed in small running script by Emperor Qianlong with Fan Chengda’s relevant poem with the title given at the end. On the last painting in the set, the Emperor further inscribed that he had the paintings specifically made in relation to Fan Chengda’s poems. The date given is the fourth lunar month of the dingmao year (1747), the latest possible date for any of the ten paintings.

Fan Chengda (1126-1193) ranks among the "Four Great Poets of Resurgence". A native of Pingjiang (present-day Suzhou, Jiangsu), he was an influential courtier, litterateur and poet of the Southern Song. Among his many achievements, he was sent as an envoy to Jin on a perilous mission, and he succeeded in negotiating for the return of Emperor Qinzong’s remains and for the relocation of the imperial mausoleums. In 1186, he composed his most celebrated masterpiece, a set of 60 poems entitled “Whimsies on Fields in the Four Seasons” that describes the scenes of the four seasons and chronicles a peasant’s life in a year.

Similar in style, “Ten Ballads on Fields and Villages in the Twelfth Month” concerns itself with the customs that were observed in and around Suzhou towards the end of the lunar year, such as dispelling evil spirits, honouring the elderly, and celebrating festivals. It brings to life the contentment of the common folk during times of peace and prosperity. Some of the customs described in the poems have survived to this day, including sending off the Kitchen God, eating what is now called "eight treasure congee", and cracking bamboo on fire, a precursor to firecrackers today.

The Qianlong Emperor loved Fan Chengda's ballads so much that he not only inscribed them in full on the paintings mentioned above but also copied them out as calligraphic works. One such scroll from the fourteenth year if his reign (1749), includes an inscription by the Emperor that credits Fan Chengda’s poems for kindling his own aspiration to achieve peace and prosperity. Picking up the hint, high-ranking officials had the imperially written calligraphy carved into jade for presentation as Lunar New Year gifts to the Emperor.

The Ten Paintings were created to be mounted onto a colossal folding screen. Entries in the Qing Imperial Workshop Records indicate that the nine surviving paintings are much narrower than the usual hanging scroll since they were intended to fit onto a folding screen. Because this was originally considered furniture, the paintings were not included in the first two series of the imperial Shiqu catalogue. The paintings were removed from the screen, likely sometime 1799 and 1816, and after they were remounted as hanging scrolls they were also impressed with the Emperor Jiaqing’s collector seals. It wouldn't have been unusual for folding-screen panels from the Yongzheng reign to be removed, replaced or put to other use when Qianlong became emperor. As for the original panels painted by Shen Yuan and Li Shizhuo, they should have been mounted as they are now only after they had been brought out of the palace so to best preserve both the paintings and the imperial seals.

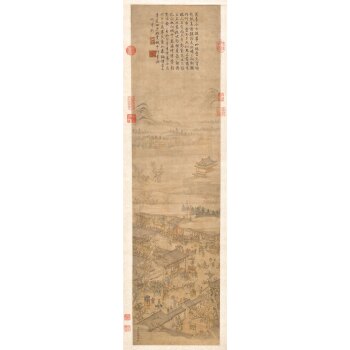

The painting bears Shen Yuan’s signature inscription, the meaning of which is repeated in the two signature seals that combine to read “painted with reverence by Shen Yuan, your servant”. At the top is Fan Chengda’s poem inscribed by the Emperor Qianlong:

In Suzhou, a land of wealth since old,

Shadow plays captivate comes Lantern Festival.

In its advent when sunny grow the days,

Filling the streets is a fair of lantern marvels.

Of gem floss here, with myriad eyelets there,

These works of gods, not of mortals,

They race to claim the fair, long and long before

Their namesake day arrives on the morrow.

Tillers taking a break from their toil

Come to town for a treat of city sights.

As if it were the Lantern Festival night,

Songs and glee swell in taverns night after night.

As if deep in spring, people’s spirits broil

Since unscathed most are from nature’s smite.

“Fortunate that my crops have suffered little blight,

I have the mood and leisure to relish these city lights.”

Scant information about the painter Shen Yuan (?-ca. after 1752), has been documented. We know that he was an artisan from Jiangnan who probably joined the drawing unit of the Imperial Workshop during the Yongzheng reign and was transferred to the Painting Workshop when Qianlong was Emperor. The information is derived from two entries in the Qing court archives, which also reveal that Shen Yuan was compensated in a manner befitting a top-ranking southern artisan.

"Archival records reveal that Shen Yuan excelled in painting portrait, Buddhist images, ruled-line painting and objects."

He was often summoned to work in collaboration with Giuseppe Castiglione, Wang Youxue, Zhang Weibang, Sun You, Ding Guanpeng, Zhou Kun and Dong Bangda, to produce mostly folding-screen panels or large-sized panoramas for palaces or resort palaces.

Shen Yuan was so versatile an artist that he was entrusted with restoring and revising works by other painters. The assignments he was given included perfecting a set of twelve landscapes with figures that correspond with the months in a year during the Yongzheng reign and touching up Gao Qipei’s architectural paintings. On the Emperor’s instructions, he studied under Giuseppe Castiglione to master perspective painting of landscapes and architecture so as to transmit the skills to his fellow court painters. Shen Yuan received commendations from the Emperor Qianlong and was bestowed with imperial silks for his good work. Generally speaking, it was very difficult for court painters, who were low in status, to be admitted to the ranks of officials. Since the early Qing, it was the practice to recognise distinguished court painters, and thanks to Sheng Yuan's expertise he was made an usher, a position of the ninth rank under the official ranking system, in 1748 at the latest.

The lantern fair was in fact a prelude to the Lantern Festival, which falls on the fifteenth day of the first lunar month. Fan Chengda’s preface to his poem suggests that the fair opened a month ahead of the Lantern Festival in Suzhou. Other than lanterns, especially those that would stand out for their novelty and delicacy, both utilitarian and ornamental articles were offered for sale at the fair.

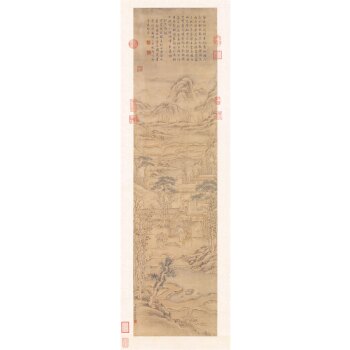

In the painting under discussion, a street scene during a lantern fair in Suzhou is depicted with succinct brush and ink. Realistically rendered, the foreground features shopfronts advertising multifarious lanterns, musicians practicing for their performances, butchers hacking and cleaving meat and women emerging to steal a peek of the festivity. In the streets thronged with all sorts of people, hawkers call out to peddle their lanterns, drawing crowds around them and making shopkeepers turn to take a look. Looked on with envy, children and servants from officials’ households proudly flaunt their newly bought lanterns. A team of youngsters manipulate a dragon lantern to the beat of drum and gong. Round the corner, some children are having fun riding in their horse-shaped lanterns. In the middle ground overlooked by a tower rising behind the parapet wall, travellers head for the city with haste in the evening mist. In the background, isolated cottages nestle in the wood, evoking a quietude that contrasts starkly with the boisterousness of the lantern fair.

As for the lanterns themselves, the variety was dazzling if the accounts of the lantern festival of Suzhou given by Fan Zhineng of the Song dynasty are anything to go by. There were large silk lanterns painted with episodes in history, small silk ones to be hurled into the air, fish lanterns that were in fact lit jars of fish, lanterns of myriad eyelets that were sewn from red and white silk shreds, glazed lanterns with disparate perforations and boat lanterns for boat races on land, not to mention those in all imaginable shapes such as lotus, cape jasmine, grapes, dog, deer, horse, etc.

These lanterns are captured in Shen Yuan's painting. There are those in the shape of animals including dragon, phoenix, toad, qilin, elephant, camel, buffalo, horse, goat, crab, butterfly, cock, duck, rabbit, carp, monkey and tiger; those in the shape of plants including Chinese cabbage, camellia, pomegranate, peach and lotus; those in the shape of everyday objects including flowers in a pot, basket or vase, teapot, incense burner, wagon, sedan chair and parasol; and those in the shape of humans including Chinese opera character, monk, Liu Hai teasing the toad, man wriggling through the hole of a cash coin and fisherman in a boat. On top of all these, there is an assortment of paper lanterns and glass ones.

Unlike the meticulous and brightly coloured palace scenes in Ice Games and The New City of Feng, of which Shen Yuan is one of the painters, the painting under discussion is more akin in style and palette to the rural snapshots in Odes of Bin, which is a collaboration with Tang Dai. The literati flavour of the Wu School of painting exudes from the elegant brush and ink while the architecture delineated in neat lines interplays with the diverse figures portrayed in the lesser expressive style. This serves to demonstrate that when the patron was as cultivated and cultured as the Emperor Qianlong, dubbed the “scholar-emperor”, the expression and techniques can aptly vary with the theme and subject, vindicating the general misconception that court painting is bound to be sumptuously elaborate.

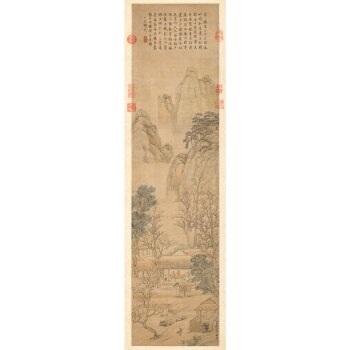

The painting bears Li Shizhuo’s signature inscription reading “painted with reverence by Li Shizhuo, your servant” and two relief signature seals that are square in shape. At the top is Fan Chengda’s poem inscribed by Emperor Qianlong:

It’s the twenty-fifth of the twelfth month lunar—

Together families gather after dinner

To share a congee made with beans in rice,

With ginger and cinnamon to spice.

Laced with syrup of cane,

More tempting than wine of grain,

It sends fiends of plagues fleeing in pain.

By headcount, out the broth is ladled,

Forgetting not infants in cradles,

Nor absentees, nor servants general.

In comes a new year, out go diseases.

Here to stay are peace, health and auspices.

From ill may our crops and livestock be spared

As the headcount congee is year after year shared.

The poem explains the Suzhou custom of serving the headcount congee to the entire family, including servants, and setting aside servings for those who were away from home so that everyone would be able to ward off plagues on the 25th day of the twelfth lunar month.

Li Shizhuo (1669-1770), a native of Tieling, Fengtianfu, was a member of the Plain Blue Banner under the Han Chinese Eight Banners and spent his late years in Zhuozhou, Hebei. His father, Li Chenglong (1650-1733), was promoted to Governor-general of Huguang during the Yongzheng reign. As for his own career in the governmental establishment, he benefited a lot from having Prince Yi (Yunxiang) as his banner commander and Nian Gengyao and his family as great friends.

Although gentle, diligent and responsible, Li Shizhuo did not live up to Emperor Yongzheng’s expectation for unquestioning loyalty and commitment and was therefore repeatedly reprimanded. From 1735 to 1753, he was in Beijing, constantly being transferred from one office to the next. Of the various posts he held, he was often addressed as the Chief Minister, an office in the Court of Imperial Sacrifices that he assumed in 1743 during the Qianlong reign. The sinecures in Beijing provided Li Shizhuo with leisure to attain accomplishment in painting and calligraphy and with opportunities to befriend members of the imperial family, literati-courtiers, monk-painters and so on. In 1753, Li Shizhuo, he was forced to retire as Left Vice Censor-in-chief for failing to attend official ceremonies thrice in a year. From then on, he stayed away from both politics and the capital. In his late years, he had to support himself and his family with his painting and calligraphy, and eventually died in poverty.

"Conversant in both painting and calligraphy, Li Shizhuo was skilled in a wide variety of genres including landscape, bird-and-flower, figure, animal, portrait and finger painting."

Characterised by texturing with a dry brush, his landscapes, for which he was most acclaimed, are mainly inspired by Wang Yuanqi of the Loudong School and are emulative of Ni Zan and Huang Gongwang. His expertise in landscape painting earned him a place with Gao Xiang, Gao Fenghan, Prince Shen and Dong Bangda among the Ten Sages of Painting.

Unlike Dong Bangda, who was a literati-courtier adept at painting and calligraphy, Li Shizhuo did not have the privilege to stay by the emperor’s side for the sake of poetry, painting and calligraphy. Yet, he would not pass up any opportunity to impress the emperor with his talent so much so that Emperor Qianlong, proud as he was of his own artistic flair, praised him in a poem (in “Ti Li Shizhuo Shulin tingzi”). More than a dozen of Emperor Qianlong’s poems were either inscribed on or related to Li Shizhuo’s paintings and some twenty works of his are included in the imperial Shiqu catalogue.

Converging with Poetic Idea of “Song on the Lantern Fair” in composition, Poetic Idea of “Song on the Headcount Congee” diverges with its monumental mountains set off by unpainted spaces instead of the rounded rolling hills typical of the Jiangnan area. Manifesting the painter’s mature style characterised by dry fine-brush treatment as in Mount Duisong, the emphases are on delineation and texturing to bring out the ruggedness of the rocks. Despite the narrative about Suzhou in the south, the ambience brings to mind the desolate winter of the north. This is due to the painter’s inextricable internalization of the styles of Wang Yuanqi and Ni Zan. Derived from Wang Hui and Li Cheng, the wintry pines in the middle ground and other trees elsewhere are distinguishable by their concise description, generous washes and elegantly pointed brushwork. In the foreground are two peasant households. While the young and old in one of the households are enjoying congee in a nondescript home beyond the low walls, a woman is working in the kitchen in another, apparently waiting for the man who is returning with some firewood. In contrast to the delicate figures in outline style that the painter modelled on Li Gonglin, the figures here are unpretentiously simple.

The circumstances leading to the scattering of the folding-screen painting set under discussion are quite different from some of their counterparts in the Qing imperial collection. Take for example Giuseppe Castiglione’s The Ten Steeds, a large-sized ten-piece set of which the two palace museums across the Taiwan Strait each houses five components. Like the folding-screen painting set that was stored in the Pavilion of Prolonged Spring, the set of The Ten Steeds was originally stowed in large chests painted with dragons in gold in the Palace of Heavenly Purity. During the Daoguang, Xianfeng and Xuantong reigns, individual component paintings were chosen and taken elsewhere such that the set was split into two. At the time of retreat, the Kuomintang took with them only the five scrolls that had been deposited in the Palace of Heavenly Purity during the Xuantong reign. Coming back to the present folding-screen painting set, the three lost component paintings were likely to have been stolen by eunuchs during the Xuantong reign so that only seven were left to be removed to Taiwan.

"Who can imagine how intertwined these two paintings had been with the vicissitudes of modern China prior to their emergence from oblivion? Once lost but now found, these rare gems will surely be obsessions that grip the hearts and minds of the initiated."

For a closer look or to read more about the fascinating history of these two rare scrolls, the full version of this article is available in Chinese.