A

lacquer box of striking beauty, dazzling perfection and massive size does not need any words to commend it. The lacquer ‘pomegranate’ box would have been an object of awe and admiration even in the early Ming dynasty (1368-1644), when imperial patronage had spurred on China’s artisans to peak performance.

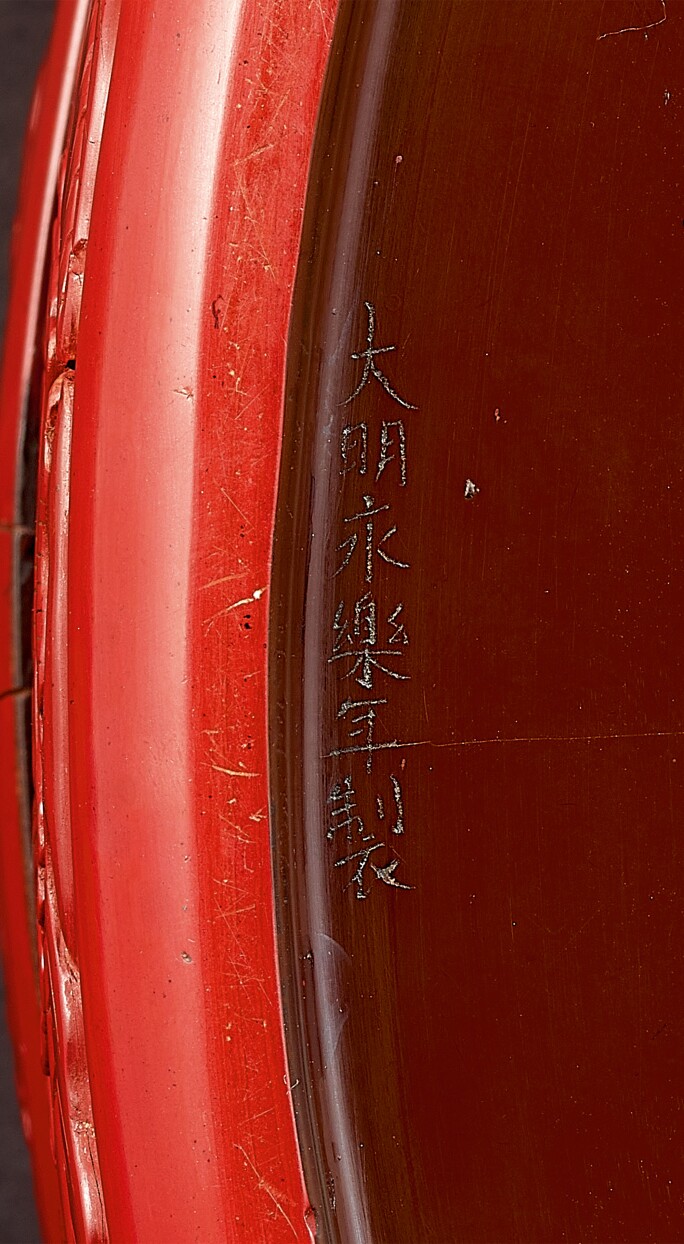

As the country’s best workshops in a range of media were recruited to produce wares for the imperial house, the bold, exuberant, but often somewhat harsh style of decoration of the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) – noticeable not only in carved lacquer ware but equally in other media, such as blue-and-white porcelain, gilt-bronze sculptures, or decorated silks – gave way to unprecedented elegance and refinement. As all rough edges were polished off, both literally and metaphorically, and compositions methodically fine-tuned, lacquer wares of the Yongle period (1403-1424) set a standard in this medium that was never again equalled, let alone surpassed, in later reigns. A by-product of this search for the ultimate was the rejection of all black lacquer in favour of the more appealing bright cinnabar red.

Unlike porcelain, carved lacquer ware with its extremely labour-intensive production process, did not lend itself to series production. Lacquer decoration therefore tends to be quite varied. Yet, like the imperial porcelain painters at Jingdezhen, imperial lacquer craftsmen appear in the Yongle reign to have been given pre-designed patterns to work from. It is most interesting to compare this box with a lacquer dish in the Palace Museum, Beijing, from the Qing court collection, one of the extremely rare pieces also carved with branches of flowering pomegranate.1 While the representation of the flowers is quite different in style and strongly suggests the hand of a different master carver, the layout of the blooms, buds and leaves is identical to that on the top of our box, and the sizes of the two pieces are similar. We may therefore assume that different lacquer craftsmen worked in the imperial workshops to given models, but were able to interpret them in their own individual manner.

Hardly any plant is as well suited to be represented in cinnabar lacquer as the vivid red-flowering pomegranate, that here is most effectively set off against the contrasting ochre-yellow ground. Yet, while pomegranate blossoms are often included in seasonal flower groups, we rarely see them on early Ming carved lacquer wares as a main design. The lush blooms with delicate, frilly petals are most distinctive due to their spiky calyx, which later turns into the crown that also identifies the fruit. While the fruit that tends to burst open, revealing its densely packed seeds, is a popular theme for works of art as an auspicious fruit symbolising many children, the blossoms’ “fiery red color was believed to ward off evil,” according to Terese Tse Bartholomew in the book “Hidden Meanings in Chinese Art.”

Boxes are perhaps the best format to showcase the quality of the carving work. The flat circular top is unforgiving in show-casing the complex layout of this horror-vacui design of prolific blossoms cushioned among greenery. It reveals how clearly the network of stems has been structured, how well the criss-crossing layers of leaves with their differently veined upper- and undersides have been balanced across the circular space, and how rhythmically the blossoms, in their different stages of maturity, from fluffy, fully opened blooms to tiny closed buds, have been embedded amongst all this.

The larger the space, naturally, the more difficult was the planning of the design: while small boxes often feature only a single bloom surrounded by leaves, larger pieces demanded more and more intricate compositions of three, five or more flowers. The present design represents one of the most complex floral designs recorded: while on larger boxes and dishes, flower patterns often are somewhat rigidly composed, with a single bloom surrounded by four others, spaced out at regular intervals, with buds in between, on this box we see a more irregularly interwoven composition of flowers of various aspects, naturalistically grouped around a prime specimen in the centre, as if arranged in a bouquet.

The present box is one of the largest Yongle carved lacquer boxes preserved. A Yongle-marked box of similar size and design, but carved with peonies was included in a 1984 exhibition at The Tokugawa Art Museum and Nezu Institute of Fine Arts, Nagoya and Tokyo. Another Yongle-marked box of similar size, similarly densely carved but with only three main blooms, perhaps roses, on the cover, from the collection of the Nanzen-ji, Kyoto, was included in the exhibition at the Tokyo National Museum in 1977, together with three of the more typical flower-decorated boxes of smaller size. Two further boxes of similar size are in the Palace Museum, Beijing, from the Qing court collection, one decorated with a landscape, the other with Buddhist motifs, both illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures. No other box of comparable size appears to have been offered at auction, but a smaller box (26.5 cm) from the Le Cong Tang collection, also of Yongle mark and period, but carved on top with peonies, previously sold in these rooms on 7 May 2002, was sold at Christie's Hong Kong, 27 November 2017.

For a closer look or to read more about the present lot, the full version of this article is available here.

NOTES

1 The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum. Lacquer Wares of the Yuan and Ming Dynasties, Hong Kong, 2006, pl. 28; and Gugong jingdian. Ming Yongle Xuande wenwu tudian/Classics of the Forbidden City. Splendours from the Yongle and Xuande Reigns of China’s Ming Dynasty, Beijing, 2012, pl. 65)