W riters and artists have long admired the Orchid Pavilion Gathering, and Wang Xizhi’s Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion is universally appreciated as a brilliant piece of prose and a crowning achievement in calligraphy. Considered an unparalleled example of running script, calligraphers through the ages have studied and emulated this piece. Over the centuries, writers, collectors, and connoisseurs have formed their own opinions of the work. During the Song dynasty, emperors held the arts in high esteem and personally excelled in painting and calligraphy. They were particularly interested in the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion, working diligently to study and practice it. These versions of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion by Emperor Renzong of Northern Song and Emperor Gaozong of Southern Song bear witness to the cultural milieu of their courts.

This scroll includes Emperor Renzong’s version of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion, Emperor Gaozong’s version of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion, and inscriptions spanning the Southern Song to the Daoguang era of the Qing dynasty. The scroll is part of late Qing, Guangdong collector Pan Zhengwei’s Tingfanlou Collection, and it was included in Tingfanlou shuhua ji (A Record of Paintings and Calligraphy at Tingfanlou). Pan Zhengwei (1791-1850), also named Yuting, with the sobriquet Jitong, was a native of Panyu, Guangdong, and the third-generation successor of the Tongfu Hang. Pan followed the family tradition and collected paintings, works of calligraphy, and stele rubbings. He was renowned for the collection of classical paintings and calligraphy housed in his pavilion, Tingfanlou. Pan compiled and produced compendiums of the best calligraphies, paintings, and other artworks in his collection. Of these volumes, Tingfanlou shuhua ji (A Record of Paintings and Calligraphy at Tingfanlou), Gutong yin hui (The Collection of Ancient Bronze Seals), and Tingfanlou ji tie (The Collection of Calligraphy in Tingfanlou) are still extant. For more than a century, the scroll was privately held by the Pan family, from Pan Zhengwei’s Tingfanlou Collection to Ronald Poon Cho Yiu’s Canton Collection.

Prior to the Daoguang era, this piece was combined with the Tang Rubbing of the Dingwu Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion (also known as the Han Zhuchuan version, which was actually a Song rubbing, currently held in Taito City Calligraphy Museum in Japan), as well as Xiuxi tu (Purification Ceremony) by Song painter He Duanli. After 1836, it was divided into two scrolls. The work was documented in the Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties, tracing its provenance over the centuries, as well as its reception by collectors over time.

Before it entered the Tingfanlou Collection, Han Rongguang owned the piece. Han Rongguang (1793-1860), who used the style names Xianghe and Zhuchuan, was a native of Boluo County in Guangdong. In his later years, he called himself huanghua laoren (which translates to Yellow Flower Old Man). At the age of 20, he was selected for national-level study, following which Han rose through the ranks from a minor official in the Ministry of Personnel to the Bureau of Appointments. In 1828, he passed the provincial civil service examinations. Han was promoted to secretary general before he became an investigating censor, and then supervising censor in the Office of Scrutiny for Justice. At age 40, Han retired from service and returned to his hometown, and he spent the next two decades teaching at Boluo’s two classical academies: Dengfeng and Longxi. He excelled in poetry, painting, and calligraphy, collectively called the “three perfections”. This scroll and the Rubbing of Dingwu Lanting were separated in 1836, after Han sold them. During the Qing dynasty, stone rubbings of the calligraphy circulated, and particularly during the Daoguang era, the scroll passed through the hands of several Guangdong collectors. Stone rubbings were frequently taken during the Qing dynasty, such asBao Shufang’s Ansu xuan shike (Stone Inscriptions of the Ansu Studio); Kong Guangtao’s Yuexuelou jianzhen fatie, Pan Zhengwei’s Tingfanlou fatie and Ye Yingyang’s Gengxiaxi guan jitie.

In the present scroll, the first section is Emperor Renzong’s version of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion. Emperor Renzong (1010-1063) used the given name Zhao Zhen, but he was born Zhao Shouyi. He was the fourth emperor of the Song dynasty, reigning for 42 years, the longest of any Song emperor. He is remembered in the history books as a benevolent leader who governed well, and “his conduct as an emperor was beyond reproach.” Ouyang Xiu wrote, “In his leisure time from the myriad affairs of the state, Emperor Renzong had no other pursuits but the brush and ink, and his feibai work was marvelous.” Few written descriptions of Emperor Renzong’s calligraphy have survived, and an extant example of his work is even rarer.

"In his leisure time from the myriad affairs of the state, Emperor Renzong had no other pursuits but the brush and ink, and his feibai work was marvelous.”

right: Wang Xizhi, Original Dingwu Copy of the Orchid Pavilion Preface, Palace Museum, Taipei, accession no. gu tie 001

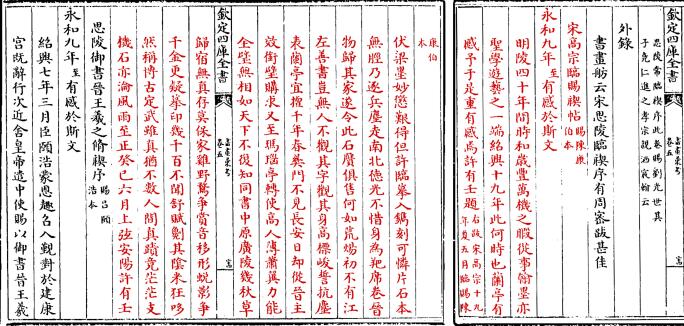

The present scroll was written on silk in powerful yet elegantly fluid brushwork. The scroll opens with two imperial seals reading “Treasure of imperial calligraphy” (Yushu zhi bao) and “Stamp for precious calligraphy” (Baohan zhi zhang). The characters for “From the imperial brush of Renzong” (Renzu yubi) in slender gold script are faintly visible at the beginning of the scroll in the upper right corner, while the Xuanhe and Zhenghe imperial seals, as well as a seal reading “Treasure before the emperor” (Yuqian zhi yin), were affixed to the end of the piece. In addition, the work bears a seal reading Mi Fu, along with seals from Qing collectors Cao Rong, Liang Qingbiao, Han Rongguang, and Pan Zhengwei.

“As for the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion, the more I examine it, the deeper its meaning becomes, and the more rigorous my emulation. Its spirit is strong, but its originality cannot be perfectly imitated. By carefully observing the brushstrokes, one can recite it from memory without losing its essence.”

The second section in the scroll is the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion by Emperor Gaozong of Song. His given name was Zhao Gou (1107-1187), and he used the style name Deji and the sobriquet Sunzhai. Reigning for 35 years, he was the tenth emperor of the Song dynasty and the first emperor of Southern Song. He was a sixth-generation descendant of Emperor Renzong, the ninth son of Emperor Huizong, and the younger brother of Emperor Qinzong. After the Jingkang Incident, he travelled south and established the Southern Song dynasty with its capital at Lin’an. Like Emperor Huizong, he was passionate about calligraphy and painting, but he was most accomplished in calligraphy. In his Hanmo zhi (Treatise on Brush and Ink), he mentions his passion for calligraphy from the Wei and Jin periods and the joy he found in emulating the work of Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi. “For 50 years, I picked up my brush every day that there were no major events.” The Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion is the calligraphic model on which he spent the most time: “As for the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion, the more I examine it, the deeper its meaning becomes, and the more rigorous my emulation. Its spirit is strong, but its originality cannot be perfectly imitated. By carefully observing the brushstrokes, one can recite it from memory without losing its essence.” Emperor Gaozong’s calligraphy made a profound impression on Yuan painter Zhao Mengfu.

Emperor Gaozong wrote his version of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion on paper. His style is profound and elegant, while the dots and strokes are round and full. The wit and delicacy of the work reflects the visual tone of Wang Xizhi’s. The work was written on a piece of white paper with cloud and dragon patterns in gold adorning the top and bottom edges. The seal Yushu zhibao was affixed in lieu of an inscription. The seal “Shaoxing” was added along the lower edge at both ends of this version, and the following inscription also appears at the end: “In the summer during the fifth month of the nineteenth year of the Shaoxing era (1149), this work was presented to Chen Kangbo.” There are many extant examples of Emperor Gaozong’s calligraphy, which we can compare with the brushwork, composition, style, structure, and materials of this scroll. In particular, Ji Kang yangsheng lunjuan (Ji Kang’s Essays on Nourishing Life), in the collection of the Shanghai Museum, is similar to this work in terms of brushwork and overall sensibility.

Historical records indicate that Emperor Gaozong of Song gave versions of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion that he had written to his senior ministers. This piece is one such example, presented to Chen Kangbo in the nineteenth year of the Shaoxing era. Chen Kangbo (1097-1165), who used the style names Changqing and Anhou, passed the highest civil service examinations in 1121. During the reign of Emperor Gaozong, he held several key positions, including Participant in Determining Governmental Matters, Minister of the Left, Minister of the Right, Military Affairs Commissioner, and the joint position of Minister of the Left and Military Affairs Commissioner. Chen Fan added this inscription to the end of the scroll: “From the treasured collection of Chen Fan on the fifth day of the ninth month of the gengwu year of the Shaoxing era (1150)” and affixed a seal reading “Chen’s personal amusement” (Chenshi miwan). Very little is known about Chen Fan, but he was the governor of Su Prefecture during the Southern Song dynasty.

Xu Youren’s inscription and poem follows this piece, which describes Emperor Gaozong of Song: “When not attending to important affairs of the state, he worked on his calligraphy, one of the facets of sagely learning and art.” Xu Youren (1287-1364) was a native of Tangyin County, part of Anyang, Henan, and a Yuan politician and writer. He used the style name Keyong and the sobriquets Guitang, Huanxi, Guitang sanren, and Keweng laoren. He was born in 1287 and passed the highest civil service examination in 1315. He served as an assistant administration commissioner, a secretarial censor, an attendant academician in the Hall of Literature, and an academician at the Academy of Scholarly Worthies. Xu Youren’s The Zhizheng Collection (Zhizheng ji) was compiled by his followers, but only Ming and Qing copies survive. Volume 10 contains an inscription and poem, but the original poem was titled Reviewing the Dingwu Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion. He did not write this poem for Emperor Gaozong’s version, but he made the following inscription after viewing the scroll: “[This was written in] the nineteenth year of the Shaoxing era, and what of today? I had feelings about the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion, which compounded [after viewing this work].” The ancient literati often felt compelled to write poems about the Orchid Pavilion Gathering inspired by their own feelings about this calligraphy work.

The scroll bears the seals of Liang Qingbiao, Cao Rong, Han Rongguang, Pan Zhengwei, Zhang Yuesong and others. The seals “Chen of Taiqiu” (Taiqiu Chenshi) and “Chen family collection of precious playthings” (Chenshi jiachuan zhenwan) may be related to Chen Kangbo, the original recipient of the piece.

According to Ming records, Xiao Zi passed the highest civil service examination in 1427. He subsequently served as a compiler at the Hanlin Academy and the chancellor of the Directorate of Education. He published an essay titled “An Inscription for the End of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion Scroll in the Long Family Collection” in Shangyue jushi ji (Collection of the Shangyue Hermit, see the 1905 edition). The essay describes the state of the scroll in the early Ming dynasty, when it was part of the collection of Long Shiyu; it included the versions from both emperors, the Dingwu Lanting rubbing, and He Duanli’s He Duanli’s Xiuxi tu.

In the early Qing, Bian Yongyu noted the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion by Emperor Gaozong and Xu Youren’s inscription in Shigutang shuhua huikao (Studies in Calligraphy and Painting from Shigu Studio, vol. 5). Ni Tao’s Liuyi zhiyi lu (A Compendium of One of the Six Arts, vol. 160) also recorded the Xu Youren inscription. In Moyuan huiguan (Conspectus on the Effects of Ink), An Qi described seeing this scroll in Liang Qingbiao’s home. In his Shuhua ji (Record of Calligraphy and Painting, vol. 4), Wu Qizhen also mentioned the work, but not the collectors. Because he often travelled from Huizhou to Weiyang, he may have seen it in a friend’s collection in Weiyang.

In the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, Cao Rong and Liang Qingbiao, both prominent collectors of painting and calligraphy, owned the scroll. During the Qianlong era, Bao Shufang owned the piece. Bao was one of the wealthiest salt merchants in China at the time, and his Ansu Studio Collection of Song and Yuan books, calligraphy, and paintings was impressive. This scroll and other calligraphy in his collection were reproduced as stone rubbings and noted in An su xuan shike (Rubbings of the Ansu Studio).

The inscriptions at the end of the scroll from the early Qing onward were made, in order, by Hu Shi’an, Tie Bao, Zhang Weiping, Bao Jun, Chen Qikun, Han Rongguang, Zhu Changyi, and Pan Zhengwei. These inscriptions clearly show the succession of collectors who owned the work from the early Qing dynasty to the Daoguang era.

Xitie zongwen (A Comprehensive Overview of Purification Calligraphy, Zhejiang circuit inspector edition) by Hu Shi’an also mentions Xu Youren’s inscription, along with Cao’s poem at the end of this scroll. The original title was “Cao Qiuyue (Cao Rong) Waiting Upon the Emperors’ Version of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion.” The inscriptions recorded in Hu’s book differ from those on the current piece, so he likely wrote them at different times or places.

The end of this scroll bears two inscriptions by Han Rongguang, added in 1834 and 1835 respectively to Emperor Renzong’s and Emperor Gaozong’s calligraphy. He praised the emperors’ accomplishments in calligraphy, inspired by his viewing experience. Based on Han’s inscription at the end of the Rubbing of Dingwu Lanting (Han Zhuchuan version), we know that he purchased it in 1832 in the capital, where it had been in Tie Bao’s collection. After returning from a trip to the south in 1836, he sold the piece to another collector. Several months later, friends showed him the Rubbing of Dingwu Lanting and asked him to inscribe it. By that time, it had already been separated from the versions by Emperors Renzong and Gaozong and the end inscriptions. Pan Zhengwei obtained the Rubbing of Dingwu Lanting (Han Zhuchuan version) in 1841, and his inscription at the end of the piece reads: “In the fourth month of the xinchou year of the Daoguang era, a friend visited with a piece to sell. Upon examination, I was astonished to discover that it was Han Zhuchuan’s Rubbing of Dingwu Lanting. I paid a hefty sum for it, and I have been admiring it day and night.” The next year, in the autumn of 1843, Pan Zhengwei purchased the versions of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion by Emperors Renzong and Gaozong for his Tingfanlou Collection. The inscriptions by Zhang Weiping and Bao Jun at the end of the scroll support this assertion.

The present scroll by Emperor Renzong and Emperor Gaozong fascinated Pan Zhengwei. His inscription at the end of the scroll notes that more than 700 years separated the Song dynasty from his own day, so it was a rarity to find calligraphy by famed artists, much less the personal calligraphy of Emperors Renzong and Gaozong. In this joint scroll, one side is strong and spirited, a triumph of vigour; the other is spring orchids and autumn chrysanthemums, a triumph of attitude. Each wonderful piece highlights the other’s brilliance. While everyone may hold their own views on the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion, since I found the Rubbing of Tingwu Lanting, why not enjoy this wonderful work in ink?

In the 20th century, and particularly in the last few decades, the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion has become a focus of academic discussion. From the Orchid Pavilion debates of the 1960s to discussions of circulation via handwriting and rubbing, this scholarly interest has gradually enriched our understanding of the histories of literature, calligraphy, and collecting. Chuang Shen spent significant time researching the scroll and published The Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion and Two Song Emperors’ Versions in 1985. The publication coincided with the exhibition commemorating the 20th anniversary of the Min Chiu Society at the Hong Kong Museum of Art, in which the present work, the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion by Emperors Renzong and Gaozong of Song, was the oldest piece. In the article, Chuang addressed many aspects of its circulation. The section on “Northern and Southern Song Imperial Versions of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion” discussed the transmission of the work and past copies; he also analysed the two emperors’ calligraphic styles and techniques and affirmed that the work was authentic. At the end of the essay, he noted that, in the evolution of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion, versions by Ouyang Xun, Yu Shinan, Feng Chengsu, and Chu Suiliang represent the Tang dynasty, while versions by Zhao Mengfu and Dong Qichang represent the Yuan and Ming dynasties respectively. We only have records of four versions of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion from the Song dynasty by Fan Wendu, Cai Xiang, Xue Shaopeng, and Qin Guan,but none of them have survived, meaning that, prior to the exhibition of the versions by Emperors Renzong and Gaozong, there were no versions of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion from the Song dynasty. These imperial versions fill this historical gap, but they also demonstrate that the history of the Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion has remained unbroken in Chinese calligraphy from the Jin to the Tang, Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties. This same work of art has stood the test of time. This piece is certainly unique in the history of Chinese calligraphy, but more broadly, it reflects the distinctive qualities of Chinese culture.

As Pan Zhengwei wrote in his inscription, it is rare to find work by noted Song calligraphers, but it is even rarer to find the personal calligraphy of Emperors Renzong and Gaozong. Collectors around the world are lucky to have a chance to own this treasure.