J ay I. Kislak’s remarkable collection is notable for its breadth and depth — it included works of Impressionist, modern, contemporary, and folk art; prints, photographs, and design objects; and so much more. But the businessman and philanthropist may be best remembered as a titanic collector of books and manuscripts. While his book collecting was as wide-ranging as his art collecting, the subjects of exploration, travel, and discovery were his greatest preoccupations throughout his life.

In 2014, Kislak donated a spectacular gift of books, manuscripts, maps, and artifacts to the Library of Congress, which are now exhibited in the ongoing exhibition “Exploring the Early Americas.” The incomparable collection documents the history and cultures of Florida, the Caribbean, and Mesoamerica. Even after Kislak’s generous donation to the nation, he continued to collect books, and on 26 April, 2022, the book world will get an opportunity to share in his magnificent collection and support the Kislak Family Foundation through Sotheby’s auction “Books and Manuscripts from the Collection of Jay I. Kislak.”

Though Kislak remained focused on exploration, after his donation he began to shift his attention further north. One of the most extraordinary items he acquired is J.F.W. Des Barres’s The Atlantic Neptune. Described as “one of the most remarkable products of human history which has been given to the world through the arts of printing and engraving,” Des Barres’s magnificent atlas covers the coasts and harbors of the Atlantic coast of North America, from Mexico to Nova Scotia. Des Barres, a British military engineer with extensive service in the New World, devoted sixteen years to his meticulous coastal survey of North America.

The charts that comprise the resulting Atlantic Neptune are the foremost cartographical achievement of the American Revolution. They depict the banks, rocks, shoals, and soundings of the coastline and provide comment and direction on navigation and pilotage. Copies of The Atlantic Neptune were compiled on a bespoke basis, principally for naval captains or merchant mariners; there is no standard collation, and no two recorded copies contain precisely the same charts.

While Kislak’s principal attention remained on the eastern coast of North America, he did not neglect the rest of the world. His interest in early navigation is visible throughout the sale — from John Harris’s 1705 Navigantium atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca, to Arctic charts used in the search for Sir John Franklin, to António Galvão’s 1563 account of Portuguese voyages (here reprinted in a later edition, after the virtually unobtainable first edition). But the apex of his interest in the Age of Discovery is, undoubtedly, his acquisition of a truly magnificent set of “The Great and Small Voyages,” published by Theodor de Bry and his heirs — the most famous and influential of such collections.

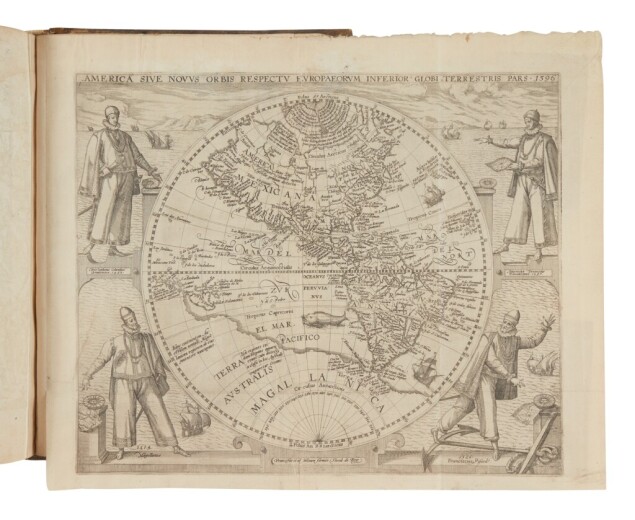

Theodor de Bry (1528–1598) first began the publication of this astounding collection following a visit to England in 1587. There he met the geographer Richard Hakluyt, who was then preparing his own depiction of voyages in the New World. Hakluyt helped de Bry find representations of the Americas, including a copy of Thomas Hariot’s “Virginia” — which would become the first part of the “Great Voyages,” published in 1590. De Bry went on to publish the next five parts until his death in 1598, when his widow and sons, Johann Theodor and Johann Israel de Bry, continued his monumental work, completing it in 1634.

“Kislak’s intelligence and discernment allowed him to build a collection that — while reflective of his personal interests — is as adventurous and exploratory as the volumes of voyages he so admired.”

The works were astoundingly popular and influential, and the iconography disseminated through de Bry’s compilation of travel narratives dominated the European view of the New World and the East Indies for more than a century. The exceptional ethnographic engravings in the first two parts are of special importance for the study of Native American life at the time of the first encroachment of Europeans.

Kislak’s interest in exploration naturally extended to a general interest in seafaring, as shown in William Bourne’s 1574 A Regiment for the Sea (the first original English work on navigation) and his 1582 The Treasure for Traveilers (the first English book to treat travel as a science), as well as Richard Eden’s 1571 The Arte of Navigation (the English translation of Martín Cortés's manual of navigation, Breve Compendio de la Sphaera y de la Arte de Navigar).

As remarkable as the auction’s individual items are, together they reveal a dynamic vision. Kislak’s intelligence and discernment allowed him to build a collection that — while reflective of his personal interests — is as adventurous and exploratory as the atlases he so admired. Indeed, an additional surprise of the sale is the scope and significance of the material not related to exploration. From Americana to literature, from early scientific discovery to visual art and music, the selection of books and manuscripts underscore the collection’s remarkable scope.

The diversity of Jay’s collecting interests is matched only by his philanthropic endeavors, which extended far beyond his donation the Library of Congress. The Kislak Family Foundation has taken up the mantle of Kislak’s many interests with its mission to support leadership and innovation in the fields of education, the arts and humanities, animal welfare, and environmental preservation. Sotheby’s series of sales of his collection, of which this is the conclusion, will assist the foundation in fulfilling Kislak’s vision and carry on his good works.

![View 1 of Lot 41: Hariot, Thomas, [and John White] — Theodor de Bry and Johann Theodor de Bry | The Streeter copy of Hariot's Virginia](https://sothebys-com.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/f435c15/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1568x2000+0+0/resize/295x376!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fsothebys-md.brightspotcdn.com%2F16%2Fad%2Fa0e0739e4027ad2cade9414356b5%2F018n10912-c24jx-t1-06.jpg)

![View 1 of Lot 88: [Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri de] — J. Geoffroy | His dictionary, used in preparing for his baccalaureate, with over 350 pen-and-ink drawings](https://sothebys-com.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/2f7f120/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1315x2000+0+0/resize/247x376!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fsothebys-md.brightspotcdn.com%2F7b%2F2e%2Fe082bb264f1680bf4631a24ff119%2F088n10912-c35rj-t1-02.jpg)

![View 1 of Lot 90: [Treaty of Paris] | The Copley copy](https://sothebys-com.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/55c8601/2147483647/strip/true/crop/1707x2000+0+0/resize/321x376!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fsothebys-md.brightspotcdn.com%2Ff8%2F80%2F7779310841499f97c57044f2477b%2F110n10912-c7rpw-t1-02.jpg)