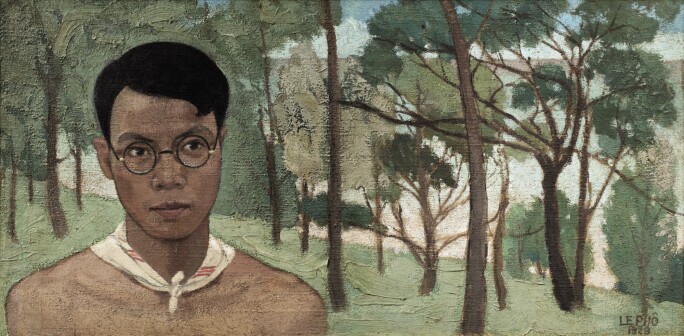

1907–1924 The Beginnings of a Modern Master

Le Pho was born on 2 August 1907 in Hanoi to a family of the Vietnamese elite. His father, Lê Hoan, was an official of the imperial court and a key ally to the French colonial government. Growing up in a place of status and privilege, Le Pho received training both in Chinese literary education and French schooling. At the age of 16, he enrolled at the Professional School of Hanoi, also known as the Applied Arts School, and in the drawing department he learnt the basis of drawing and painting, proportion and colour. At the time, the school was considered a precursor for candidates to the prestigious École des Beaux Arts de l’Indochine. From this early period, there are only three known extant oil paintings by Le Pho, all executed in 1924 when the artist was just 17, and now held in private collections. Reflecting the academic style taught at the Professional School, the paintings are portraits depicting his father, sister, and brother-in-law.

1925–1930 Orientalism and Gauguinism

In 1925, when Le Pho sat for the examination to enter École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine, he ranked ninth out of 270 candidates. At the school, mornings were dedicated to drawing, painting or live model sculpture taught by French artist Joseph Inguimberty, while afternoons were devoted to the study of East Asian decorative arts taught by Vietnamese artist and École co-founder Nam Sơn. From 1926 to 1930, Le Pho also studied under Stéphane Fernand Brecq, Antoine Ponchin, and Paul-Émile Legouez, with his two final years under the direct supervision of Victor Tardieu, co-founder and headmaster of the school. During these formative years, Le Pho honed his oil techniques and learned painting on silk. He also learned lacquer art. Each day after class, Le Pho would often go straight to the school’s library to read books on Tang and Han sculpture, and Song and Ming painting as well as references on decorative arts from various countries and periods. He noticed that the library lacked books on Vietnamese art which at the time could only be studied informally through personal observation because it was not considered a true branch of art history. Tardieu’s goals for his students was very clear: “To guide their taste, to prevent them from misdirection, and to help students understand the beauty of past forms.” In this mission, he was expressing his view on the decline of Vietnamese art, which while resolutely colonial and Orientalist in its core, was a founding concept of École.

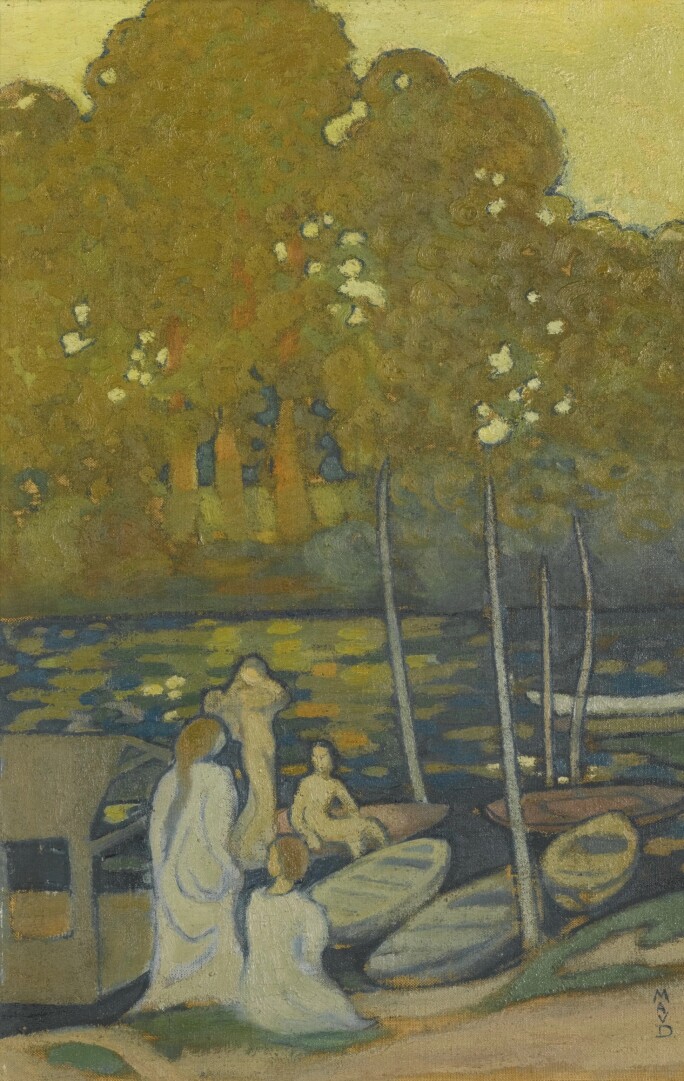

Le Pho’s work during his time at École was marked by the Orientalist dynamic of the establishment. None of his paintings alluded to colonisation or to the French presence. Encouraged by his teachers, the paintings presented “a rectified Orient, an orientalised Orient”, a term coined by scholar Edward Said. Le Pho was particularly attentive to the descriptive value of his work – clothes rendered meticulously, and architecture and furnishings precisely detailed. They were meant to express images of a peaceful and idealised Vietnam. He favoured contemplative scenes inhabited by calm and static figures. They gaze outwards or inwards at a distance, preoccupied by their own introspection or melancholy. It’s clear that Le Pho’s own personality was beginning to unfold in his art; his brushstrokes became thicker and more generous. This approach is also marked by the use of a dark outline undeniably informed by the Symbolism and Synthetism art movements. Such influences transpire in his depiction of plants as well; the leaves, stems or trunks, stretched and twisted, reminiscent of the paintings of Maurice Denis.

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

In 1930, Le Pho completed L’âge heureux as a brilliant testimony to his five-year quest as well as a clear homage to Paul Gauguin. This painting would earn him the silver medal at the 1932 Salon des artistes français in Paris. The composition, parted in two planes as hill and lake, along with the stylisation of the plants, the young woman seated in the foreground and the silent interactions and interiorised expressions of the figures evoke Gauguin’s Tahitian works of the 1890s. Although art history lessons delivered by the school did not include modern movements, students of École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine were also educated through the practice and teaching of their professors. For Vietnamese artists, this paved the way to create linkages between Symbolism and Synthetism and East Asian arts. It is through these influences that Le Pho’s work of the period appears in continuity with Vietnamese pictorial style. Nguyen Thuy, a fellow student at École, would later say, “The art of China is at our door but we search for it beyond the oceans.”

1931–1932 International Exhibitions

In the spring of 1931, just one year after graduation, Le Pho was sent to Paris by Tardieu to work under Pierre Guesde, then Chief Commissioner of the Indochinese pavilions for the Paris Colonial Exposition. Le Pho was in charge of École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine’s exhibition presented inside the monumental replica of Angkor Wat, erected in the Bois de Vincennes. For weeks on end he did not leave the premises, attentive to every detail. He decided each painting’s location on the wall, oversaw the last patina application on the sculptures, and made sure nothing was damaged during handling. Amongst the hundreds of artworks sent to Paris by the school, Le Pho selected L’âge heureux and Tristes souvenirs, a pair harmoniously matching in colours and personality, as well as a monumental four-metre high hanging scroll depicting a classic Vietnamese dancer, a painting introduced the previous year in Anvers, Belgium. Le Pho also created several lacquer pieces, folding screens and furniture that were exhibited. The show was a real success, acclaimed by the press and the critics despite anti-colonial oppositions led by both French and Vietnamese groups.

This exposition assumed a decisive role in Le Pho’s career. It was the first time his work was seen by such a massive and international crowd of around eight million visitors, extensively covered by the press and building up his notoriety. It was also an important step in regard to his role as curator, as art historian Phoebe Scott puts it, allowing him to develop a more global vision of what Vietnamese modern art is. Finally, this show was an opportunity for Le Pho to leave Vietnam for the first time and discover Europe. His fellow artist and friend Vũ Cao Đàm joined him in Paris in December that year. Whereas the latter enrolled at École du Louvre to study Chinese art history, Le Pho entered École Nationale des Beaux-Arts to keep perfecting his technical knowledge, following the example of his professor Nam Sơn who had attended classes there just a few years earlier in 1925.

At the Prima Mostra Internazionale d’arte Coloniale in Rome, Italy, in the winter of 1931, Le Pho presented three paintings executed in Hanoi before his departure. A photograph of the time shows the artist, his easel next to him, surrounded by the three canvases. They all show a substantial change in his approach to modern art. Jeune fille en blanc displays an Orientalist take not so dissimilar to his previous works. Yet, the minimal architectural background already signals his attempt to evolve beyond it. With Femme nue, also known as Extase, Le Pho proposes a whole new vision. Borrowing from Gauguin as to the woman’s posture, the painting depicts a naked white woman lying on the floor on a bed sheet. The vase of flowers behind her alludes to the theme of the Annunciation, when the Virgin Mary learns she is carrying God’s son. With this one painting Le Pho breaks away from Confucian principles of female modesty, mocks the Catholic Church and insults the colonial order. Femme nue, subverting the odalisques of the Orientalist school is, this time, a white woman eroticised by a non-white artist. However the painting is deemed too Western and fails to find a buyer. Le Pho is expected not to ward off Vietnamese subjects. For the artist who, with this canvas, submitted the most daring piece of his young career, it was a hard truth to swallow.

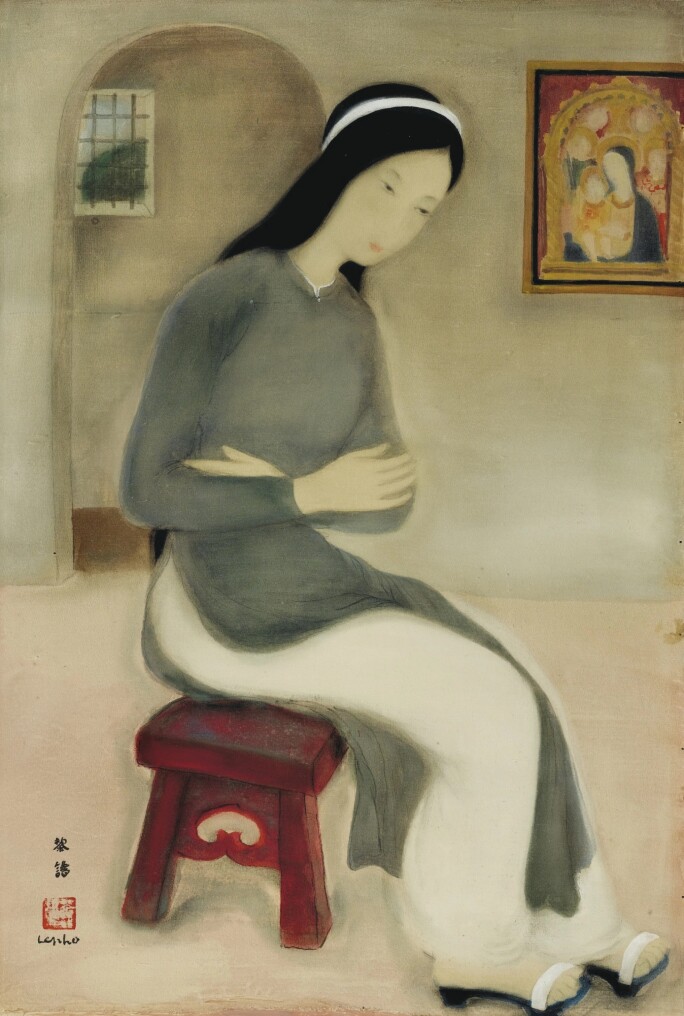

From then on Le Pho set himself on a new mission, in search for an identity that could embrace those constraints and sublimate them into a complex and authentic individuality. Accompanied by Tardieu who had also sailed to France for the Exposition Coloniale Internationale, Le Pho discovers Western Europe. Their itinerary presumably followed the various shows where École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine participated. In addition to wandering through the French countryside, the two men also went to Italy where they visited Fiesole, Florence, and perhaps Rome. They also travelled to the Netherlands, to Bruges in Belgium and to Germany, where a fair is held in Cologne. From this grand tour Le Pho brought back sketches of architecture and landscapes rather than copies of old masters. Le Pho’s lyrical biography published in 1970 by art historian George Waldemar insists on the epiphany that is the discovery of Primitive artists. The work of 15th century old masters such as Jean Fouquet, Sandro Botticelli and Hans Memling held a great impact on Le Pho’s mind. Their slender forms, the subtlety of details, the prevalence of the line and the symbolic value of motifs appear not so disparate from Chinese or Japanese painting. The resolute influence of this trip on Le Pho’s work would not appear for a few years, after which they endlessly reappear as aesthetic or conceptual takes.

1932–1937 Final Years in Vietnam

Upon his return, Le Pho is appointed drawing teacher at the Lycée Albert Sarraut in Hanoi. In all, including his time teaching at École des Beaux Arts de l’Indochine, Le Pho’s teaching career lasts for seven years, instructing the likes of Lưu Văn Sìn and Nguyễn Gia Trí. Teaching positions were much sought after by the graduates, a lot of them struggling to get a steady and sufficient income after leaving the school. The clientele for Vietnamese modern art was very limited and commissions were rare. The press criticised the school, stating École impoverishes Vietnamese society by taking its sons away, leaving them with no purpose nor employment but only misery, delusion and bitterness. Le Pho is lucky enough to ignore that precariousness and another newspaper informs us that Le Pho and Mai Trung Thứ were envied by many former students. While Mai Trung Thứ is sent to teach in Huế, Le Pho stays in his native Bắc Kỳ. Perhaps he returns to his former studio by the lake for we recognise in his paintings the same lakeside landscapes and pontoons as before.

That year Le Pho also introduced his earliest silk painting we know of. La cueillette des simples features the same lake and displays the same interest in twisted depth, but seems to have caught up with the lesson of fellow silk-painter Nguyễn Phan Chánh whose art had been particularly successful during the Exposition Coloniale Internationale. Indeed, Le Pho adopts a pared down composition, centered around three figures placed in a pyramidal composition typically found in Nguyễn Phan Chánh’s silk paintings. Silk painting has an ambiguous identity; seen by the public as a technique characteristically Vietnamese, a tribute of the modern artists to their ancestral culture, and it is also claimed by Tardieu as his own invention. Already employed by Vietnamese artists during the 15th century, painting on silk eventually lapsed and got replaced by painting on paper. In neighbouring China and Japan, painting on silk never disappeared and it is their practice that inspired École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine. It was at this time that Le Pho’s Cueillette des simples was sent to Paris where it was bought right away, even before being framed. It is a success for the artist who challenged himself and delivered a piece that is both appealing to collectors and true to his art. His friend Vũ Cao Đàm writes to Tardieu, “I’m happy to see that my fellow artists now understand it is in their best interest to only do paintings on silk.”

While in 1936 Le Pho visited Cambodia, it is his travels to China in 1934 that carries the most influential mark on his career. First becoming familiarised with the collections of his father, tổng đốc Lê Hoan, and later on through Asian art history studies at École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine, Le Pho sought to expand his knowledge of Chinese arts. In Beijing he visited the Palace Museum, a former Qing imperial citadel turned public gallery since 1925. Although one year before his visit, the museum had started to evacuate thousands of pieces for fear of a Japanese invasion, Le Pho was still able to admire a fraction of the enchanting collections. The masterpieces of painting, lacquer and jewellery he observed had a tremendous effect on the artist and nurtured his growing taste for preciosity and aesthetic refinement.

Le Pho goes on to visit the National History Museum where priceless antiquities such as carved stones, ceramics, and bronzes were kept, teaching the artist lessons about volume and materials. Le Pho also had the privilege of being introduced to private collectors opening their doors for him. Back in Hanoi the artist started digesting the fruits of this eye-opening travel. In his studio he undertakes a new silk painting, a synthesis of his reflections regarding which role to give Chinese and Vietnamese art in his work. Femme assise indubitably evokes ancestor portraits he had viewed in China, its elongated dimensions, the focus on one central character, the ochre hue embracing the figure. However the woman is seated on the floor, thus alluding more to ancient Vietnamese ancestor portraits than Chinese ones. In the same composition, the hanging scroll hung behind the lady is typically Vietnamese, a popular tiger print, sold by woodblock artists during festivals. Le Pho thereby proves his will to build his own style, nurtured not only by the teachings of École but also through Vietnamese art history and with his own visual culture, no doubt motivated by his travels to China.

Le Pho’s embrace of Vietnamese arts is also revealed by the prevalent place portraits progressively get in his work. Neglected by the teachings of École, portraiture is an essential part of Vietnamese art history. It is indeed the most common art genre after religious sculpture. Infused with Buddhist and Confucian beliefs, portraits are an unmissable facet of Vietnamese art and can be observed everywhere from temples to domestic altars and public spaces. In 1926, a few months after the opening of École, tổng đốc Hoàng Trọng Phu suggested the school should train portrait artists who would assuredly find many customers among the Vietnamese bourgeoisie. An oil portrait dated 1935 kept in the Vietnamese National Fine Arts Museum depicts a woman seated on a chair. Her intense presence and sculptural volume denote Le Pho’s knowledge of contemporary movements such as Art Déco. Her expression is sensible and melancholic, an enduring feature in Le Pho’s art. As the artist understands the appeal of portraiture, his Vietnamese clientele grows. He is invited to Huế by Emperor Bảo Đại who commissions the artist to paint his portrait and his wife’s, Empress Nam Phương. Since visiting École in 1933, when Bảo Đại expressed his admiration for the artist’s portraits, the Emperor never forgot Le Pho. During his stay at the imperial city, Le Pho is also asked to realise a lacquer decor, renewing the experience he acquired in 1931 when Governor General of French Indochina Pierre Pasquier tasked him to conceive a lacquer decor for his official residence. At the fair launched in 1935 by the Société Annamite d'Encouragement à l'Art et à l'Industrie, Le Pho presented three portraits, demonstrating the paradigm shift seen in his career since the Exposition Coloniale Internationale where he featured three genre paintings. One of those portraits depicted forward-thinking mandarin Hoàng Trọng Phu, an old friend of Le Pho’s brother-in-law. In this full-length portrait, the mandarin appears standing on his two feet, a relatively rare formula. The artist picked a personal and intimate reference, finding inspiration in an old photograph of his father Lê Hoan. As for the landscapes he painted at the time, they moved towards more stylisation in their colours, volumes and forms. Interestingly they show the same concern as the ones created in Italy with the harmonious unity of architecture and nature. Alongside the Chinese inspired still life paintings Le Pho also executed during this period, they softly counterbalance the intoxicating power of his portraits.

Le Pho’s permanent exploration in the name of a renewal of Vietnamese art does not limit itself to painting and lacquer, it also touches decorative arts and fashion. Textile work is indeed an important part of this generation of artists. Former students of the École des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine experimented and established a new fashion era. In mid-1930s Hanoi, Le Pho’s designs were first limited to a few friends before he eventually started running an actual fashion house. The áo dài dresses he designed let white, frilly cuffs pop-out at the wrists as in the Renaissance court portraits he enjoyed in Florence. Not only does he think of clothes, he also conceives jewellery. Adapting the classic Vietnamese parure but worked in niello rather than gold, Le Pho’s creations are proudly Art Déco.

Painter, lacquer artist, teacher, decorator, fashion and jewellery designer; Le Pho’s creative energy and faith in a new age of Vietnamese art was boundless. From academic to Orientalist teachings embracing his Vietnamese heritage and nurturing his creations with European primitivism and Chinese court art; across what was almost 15 years, Le Pho pushed his art forward, attentive to his audience and to his own desires, accompanying the development of Vietnamese modern art. In 1937, Paris was preparing for a new international fair, the Exposition internationale des arts et des techniques appliqués à la vie moderne. Le Pho sailed to France, determined to put his curatorial skills to use. He directed the setup of the Indochinese pavilion following his artistic instinct and his intimate knowledge of Vietnamese art and European audience. A few weeks after Le Pho’s arrival in Paris, his mentor Tardieu dies in Vietnam. His parents and his older sister are long gone too. But in Europe, Le Pho’s friends Lê Văn Đệ and Vũ Cao Đàm have been thriving for the past few years, answering commissions and journalists. Le Pho knew it was time for a new chapter in his career and personal life. He would not return to Vietnam. France was from then on his new home.