N oel Anderson’s studio is in the Bronx, located just a few subway stops from where he lives in Harlem. I’ve been here before—in a way. But I couldn't really grasp the scale of some of his work on our Zoom call. Anderson suggests that I stand on a step stool to get the full view of the nearly ten-foot tapestry on the floor. An image of Nina Simone had been woven in it. The piece takes up enough space in the studio that Anderson’s dog, Thelo, can’t help but skitter on top of it from time to time. “Thelo,” Anderson points out, is short for “Thelonius,” as in Thelonius Monk, his late father’s favorite musician. Thelo seems particularly fond of Will, Anderson’s studio assistant. At one point, Will cradles Thelo in the crook of one arm while settling in for a day of distressing one of Anderson’s ‘basketball player’ tapestries with the other.

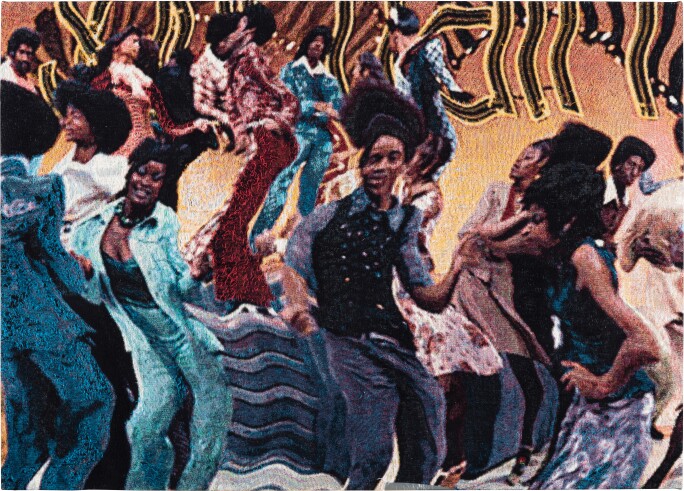

Anderson often manipulates the surface of his work. He either loosens the threads by hand or softens the texture of the weave with a coarse brush. Up close, his tapestries resemble worn-out sweaters. To him, this makes the pieces vibrate—in the same way the subjects in the photographs he chooses for them vibrate. Like the woman striking a pose during an episode of “Soul Train.” Or the dancer dropping to the ground to complete a move, his legs looking like Gumby’s; his flexibility Anderson then emphasizes by stretching that part of the tapestry. The whole scene, actually, has been warped in a way that mimics the wave-like distortions psychedelics can produce.

One large-scale tapestry in his new show, opening this October at Paris+, that Anderson intends to install like a towel draped on a clothesline (à la Sam Gilliam), has a scene that he constructed by superimposing an image of a wedding couple onto another of a “Soul Train” line. The takeaway is that “the line is cheering this couple on,” he explained. On top of that, the image in the tapestry—like a number of his others—looks like how someone with double vision would see it. Anderson describes this work as the show’s “hook.” And “damn it, you're always going to sing the hook,” he said. The imagery demonstrates how dance can inspire Black tradition and Black joy. But it also evokes much more than that. As Sotheby's Paris hosts a selling exhibition of his work, on display until 10 November, Sotheby’s magazine spoke to Noel Anderson about how in his trajectory as an artist, he’s working to find “the internal spirit that is Black people,” he said. And also, to keep that spirit safe.

So how did this work on Black performance come about?

I’ve got four or five things I'm working on at once, and one of those things is the movement of Black bodies. And a part of that emerged from when I used to be a performance artist.

Oh, really. What kind of performance art?

It was a lot of physical performance, pushing the body against objects—like the wall. For my last performance, my father has just died. And I was reading stuff about astral projection, and how you can take the mind and do things with it. For that show, some of the performers dressed up as women, like really bad drag.

I had frozen a bunch of objects into blocks of art. I set it up like a variety show. And the main act was we would stare at these blocks of ice and try to get them to melt with our minds.

How long did that go on? I want to understand the bandwidth of an audience watching people breathe on blocks of ice.

The audience? More like: How long can I stare at a block of ice?

And where did you stage this performance?

At Yale. I was doing a lot of performance then. And then I got into the real world. The problem with performance is you have to consistently generate.

And it’d be too hard to work at that pace?

Yeah, so I went back to what I knew—which was images. I was working with this dealer Jack Tilton at the time. And he was saying, you have to go to the [Metropolitan Museum of Art] on Friday night.

Because all the great artists go then—artists like Richard Tuttle and David Hammons. And I would go there looking for them.

Did you ever find them?

No. And I was like why [am I even doing this]? Because then I watched the documentary with Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, and [the interviewer] asked them, ‘well, you know Duchamp, why aren't you carrying on his lineage?’ And they both laughed very similarly—in separate interviews—and they said, ‘why would we want to figure out something he already did?’ At which point I was like, ‘why should I go figure out something Richard [Tuttle] already figured out?’

So for me, [I found inspiration] in the Medieval wing in the Great Hall. And I remember sitting on that bench and staring at this huge tapestry. And I was just mesmerized.

So that's how you started working with the medium?

Yeah. And I was like, nobody's doing this work. And if they are, they're confined by the term craft.

Were you ever worried that you’d be constrained by the same terminology?

No, not really.

What part of the history of weaving did you find so attractive?

Part of getting people to get more out of the work is trying to get it to give them the sources they know. I feel like that familiarity gets to people subconsciously. They think to themselves, ‘Why does this feel so familiar?’ But it’s not really because of the Black folks in it. So the art historical thing is to try to put us back in the canon in a way, but also to explode the canon.

And I think France is a good place to do it because the history of the material itself is French.

So how long have you been working on this performance series?

Like a year. I would also say longer than that, in that I would advocate that it starts with my works [that depict] the athletes.

But even going further back, you feel like it's connected to the performance work you did like way back in art school?

Yes. Because all of it's about the extension of the Black body. It's like, ‘What is the Black body required to do? And what can it do beyond its own expectations?’

[The medium] allows me to push the body in different ways, specifically with the draping—I can extend the body. I can fold the body into itself.

But it also protects the Black body because things fold in on themselves and you can't really get into those things.

Was there some sort of through line of the pieces you chose for the show?

Collectively, it feels like you're in a space where everyone is dancing.

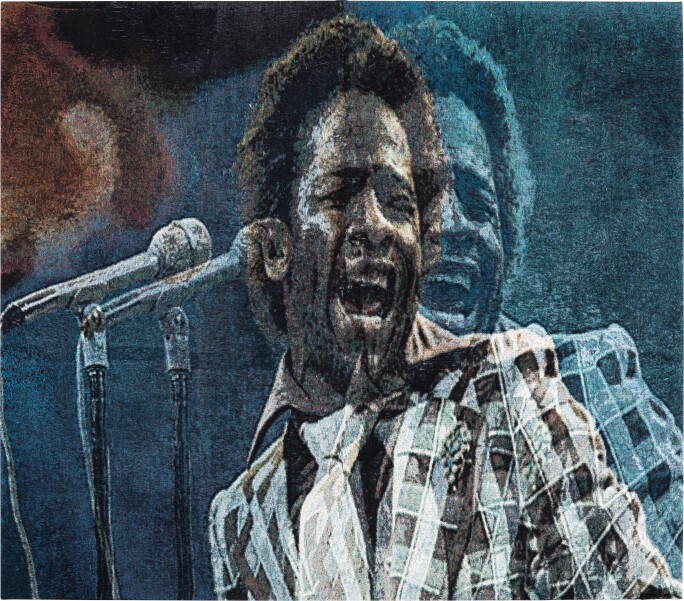

There’s a large one in the show that’s based on Al Green. He's the talent. And the idea is to build a space in which it feels like this guy is performing. And these people are dancing to it. It’s kind of a celebration of this aspect of Black love. And that this Black performance has to have some kind of generator—a Black voice.

In talking about the Black performer, it started with the basketball player, because I knew this is what people understood—at least as far as incorporating the body in my work.

And the shift from athletes to singers is just a continuation of the theme?

It is. When I write critically about art, I use a lot of singers as entry points or bridges between sections. Throughout one essay, I use Parliament Funkadelic’s Flash Light [as a metaphor] to talk about what the protagonist in that song is searching for—-which is really Blackness. I use that flashlight to talk about how I'm also in search of something in my work. [Which] is the internal spirit that is Black people.

Main image: Noel W. Anderson, Patsey, 2022