"The OTAKU, the passionate obsessive, the information age's embodiment of the connoisseur."

'Otaku' is a loaded term used to describe usually males who obsessively consume and collect manga, anime, gaming, girl idols, model figures, and other merchandise related to these forms of popular visual culture. The emergence of an otaku subculture as a major phenomenon in the 1970s and 1980s had become both the source of widespread fascination as well as the cause of a moral panic over the perceived degeneracy of Japan’s young fanatics.

"No matter where they go, [they] cart around tons of books, magazines, fanzines, and scraps stuffed into huge paper bags like hermit crabs."

In the 1991 polemic ‘Communication Deficiency Syndrome’, literary critic Azusa Nakajima saw the extreme self-absorption into worlds of fantasy and games as a sign of mental instability. This was more than just harmless escapism. The otaku was seen as incapable of real human relationships, socially inept and unable to succeed in mainstream culture. The fact that they clung so inexplicably to a fringe set of values made them even more despised, an easy target.

In the past three decades, however otaku culture has undergone an image overhaul. The reason perhaps may be that fan subcultures have gained greater acceptance. Or the reach of otaku has grown spectacularly, going on to influence generations of artists and writers. Or in the era of smartphones, that complete self-absorption into content isn't so inexplicable.

The last decade has seen the ascendance of geek culture; the obsessive devotion to a pursuit has become a thing to be celebrated not denigrated – and in such a climate one might imagine fanboys, hobbyists, cosplayers, gamers, technophiles and all the various factions of geekdom worldwide joining hands with their otaku cousins. Certainly the internet has made it easier for the otaku to curate content and find others with shared affinities, while social media thrives on the staggering volume of content created and shared widely by communities of enthusiasts and eccentrics.

Connoisseur in the Information Age

In a 2001 essay ‘Modern boys and mobile girls’, the science fiction novelist William Gibson observes the way technology has driven cultural change, singling out the otaku as ‘the passionate obsessive, the information age's embodiment of the connoisseur.’ He elaborates: ‘Understanding otaku-hood, I think, is one of the keys to understanding the culture of the web. There is something profoundly post-national about it, extra-geographic. We are all curators, in the post-modern world, whether we want to be or not."

Often, the otaku have a specialised fixation, perhaps something that might be called ‘secret brands’, which they might hunt ‘on specific, narrow-bandwidth, obsessional missions’, according to Gibson. ‘There is a similar fascination with detail, with cataloguing, with distinguishing one thing from another.’

In a June 2021 interview with The Brooklyn Rail, the artist Brian Donnelly, better known as KAWS, discussed that particular way of collecting. As with Gibson, KAWS noted that in Japan, collectors of vintage toys, action figures, and cards have turned these pursuits into an art.

KAWS said, ‘I grew up very conscious of [the commodification of toys], with Star Wars and that whole collector mentality about keeping everything C-10 mint. When I was first going to Japan, I saw what was collected there, and the obsessiveness and the connoisseur-ness of it. I loved that… People tend to think, “oh, collector,” and immediately they’re thinking art, and then in this day and age probably contemporary art, and to see people fully absorbed in what they’re collecting in different fields with the same sort of integrity and the same sort of knowledge of where it’s come from… I saw in Japan how the material looked so great, and so obsessive. Especially with vintage prototype Star Wars figures and things like that. It’s hard not to look at them like you look at any other art object.’

Dark Roots

The term ‘otaku’ has a negative connection based on its early association in 1989 to child serial killer Tsutomu Miyazaki. The ‘otaku murderer’ was so named because police investigators found his room filled with pornography and anime. The mass media tarred the entire group with the brush of sexual deviance and violent fantasies. They were described as socially stunted maladroits whose withdrawal from the real world posed a real danger to society.

While the world of anime and manga may teem with graphic and unnerving imagery, the blame is misplaced, according to psychologist Tamaki Saitō. There is a clear separation and distance between the erotic imagery and the real world, because for the otaku the fiction is the object of desire, he says. According to Saitō, ‘The behaviour that sets otaku apart is the act of loving the object by possessing it.’

Otaku Sexuality

In an interview , contemporary artist Takashi Murakami, who considers himself part of otaku, remembered his own reaction to the sensational coverage of the gruesome murders in 1989: ‘When Miyazaki's room was revealed to the public, the mass media announced that it was otaku space. However, it was just like my room. Actually, my mother was very surprised to see his room and said: “His room is like yours. Are you O.K.?” Of course, I was O.K. In fact, all of my friends' rooms were similar to his, too.’

‘I became an otaku when I was in high school and absorbed many different things from anime like its erotic and fantasy elements. That very process resulted in this work,’ said Murakami in a 2013 interview with CNN, referring to the sculpture Hiropon (1997). Many of the artist’s iconic and hyper-sexualised sculptures are entrenched in the erotic domain of anime and manga – an integral facet of Murakami’s heavily otaku inspired practice of the mid to late 1990s, which gave prominence to erotic male fantasy.

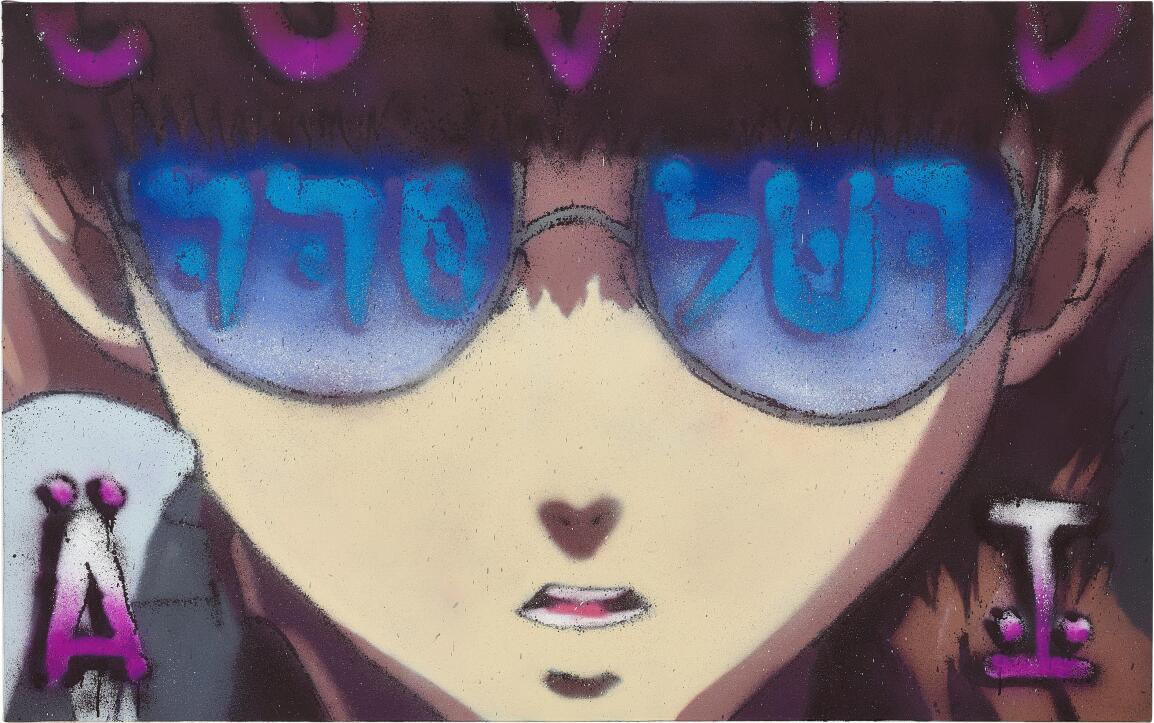

The world of anime and manga is filled with bishōjo, beautiful girls usually depicted with innocent doe eyes and an alluring waif-like figure. She is a fictional dream girl that exists to inspire moe, an admixture of brotherly affection and attraction, which is a prominent part of otaku fantasy.

Overlapping with the development of otaku is kawaii culture, which also emerged from the manga tradition. Kawaii entered into the global artworld lexicon in the early 2000s, but it is an aesthetic that has evolved over decades from its roots as a subculture aesthetic to a global phenomenon. Often translated a 'cute', Kawaii has a far wider semantic range, from being sweet and lovely, to pitiable and pathetic. Childlike innocence is an important notion within kawaii culture. Even adult consumers of cute material goods are in a sense gesturing toward a certain youthful fantasy, a recovery of an earlier emotional state. As distinct from products that are expressly designed for children, the kawaii characters are themselves the embodiment of a lost childhood.

Driver of Contemporary Culture

The proliferation of a world of cosplay, anime, manga and sexually suggestive figurines was the means by which Japan dealt with the aftermath of the Second World War, according to Murakami. The manga tradition, a visual form of serial narrative, is responsible for the ubiquity of this aesthetic in everyday life in Japan. Manga emerged in the post-war period as a form of popular entertainment, and through its success evolved far beyond the medium as a true driver of contemporary culture. Otaku themes find their origins in the unique historical context of post-war Japan, cultural critic Hiroki Azuma writes in Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals. However, he sees contemporary otaku culture as a phenomenon not necessarily unique to Japan, but forerunners of a postmodern mode of consumption. Otaku modes of expression are a response to generation-making events that shape our world.

Connoisseurs of Visual Culture

In the past several decades, scholars have undertaken the task of rehabilitating the image of the otaku. Toshio Okada, co-founder of the animation studio Gainax, wrote the book Introduction to Otakuology (1996), in which he redefines them as the quintessential cultural collector with a keen sense of taste and sensitivity for detail.

‘I believe otaku are a new breed born in the 20th century visual culture era. In other words, otaku are people with a viewpoint based on an extremely evolved sensitivity toward images.’

The otaku has three modes of seeing, through: the eye for style (iki no me), the eye of the artisan (takumi no me), and the eye of the connoisseur (tsū no me). As highly advanced consumers and appreciators of culture, the otaku is poised as the “legitimate successors of Japanese culture”, according to Okada.