D r. Ryutaro Takahashi, the renowned psychiatrist and an art collector, is the proprietor of one of the foremost collections of Japanese contemporary art. His collection comprising more than 3,500 artworks has been exhibited across more than 20 museums around the world. It is a collection that weaves together a diverse tapestry of Japanese post-war artists, including Takahashi Murakami, Yoshitomo Nara, Makoto Aida, and Kohei Nawa.

Dr. Takahashi was born in 1946, when the national mood in Japan was dominated by a solemn narrative of rebuilding and rebirth; later, he participated in the Zenkyōtō student movement that spread like wildfire in the political and artistic cauldron of the 1960s. With this backdrop of contrasting moods, reconstruction, and experimentation, a passion for art collecting was born. His first acquisition, made in 1979, was a small oil on canvas work titled Greta Garbo (1975) by Goda Sawako. In the 1990s, by now a practicing psychiatrist with his own premises and walls to fill, Dr. Takahashi’s collection grew quickly.

Dr. Takahashi’s collecting is grounded in a wish to live and collect in the here and now. Across the span of several decades since he began collecting, the world has witnessed huge societal changes as the urgency of postwar rebuilding faded, as boom turned to bust, and as landmark events such as the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami (also known as the Great East Japan Earthquake) left their mark. In recognition of his significant contribution to the promotion and popularisation of contemporary art amidst these vicissitudes and changing fortunes, Dr. Takahashi received the Agency for Cultural Affairs Commissioner’s Commendation in 2020.

Few artists have played as central a role in Dr. Takahashi’s collection as Yayoi Kusama, with whom he respects most to the present day. He first came across a video of her anti-war Happenings in New York in 1968. Since then, he observed in an interview with Sotheby’s, “Yayoi Kusama has been my eternal muse.” He began collecting her work in the 1990s, alongside those of the Mono-ha (“School of Things”) artists.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that a psychiatrist should find himself so drawn to an artist troubled for so long by mental illness (Kusama voluntarily admitted herself into a psychiatric hospital in 1977). For Dr. Takahashi, the healing and rehabilitating powers of art are key to understanding the artist. “If we look at how Kusama devoted herself to art as a method of healing, a way of overcoming the risk of psychological collapse, in her case it was a very effective form of therapy and has given very good results,” he once explained in an interview with Arterritory.

In order to understand a person, or a painting, understanding its history is important. To understand Hat, we must first return to the 1960s. Kusama’s acclaimed Infinity Net paintings from that decade were works of great directness and verve, overwhelmingly executed in a monochrome palette. Dr. Takahashi acquired his first “net” painting at an Ota Fine Arts exhibition in 1998, which exhibited Kusama’s latest oil paintings to great fanfare. The collector was thrilled at the artist’s return to the medium of oil, after her acrylic dots of the 1970s and 1980s. With his unique professional insight, the collector understood the technique both in psychological and emotional terms: “Yayoi Kusama shows a compulsive tendency to fill space with nets and dots. This was her way of coping with the fear of space caused by visions and auditory hallucinations she experienced as a young girl. All of the Infinity Nets leave a poignant impression,” he noted in a recent interview with Sotheby’s.

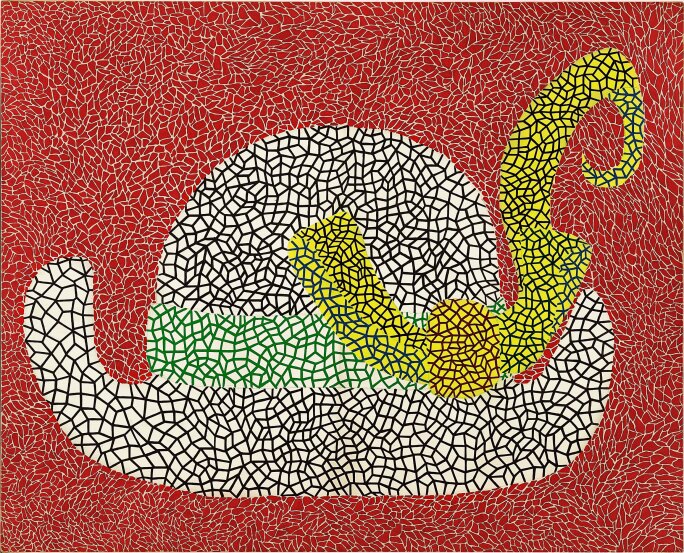

Hat, a work of vibrant, resounding colour, marked a new period of experimentation and a break from the prevailing monochrome of Kusama’s past oeuvre. It was first acquired from Fuji Television Gallery in Tokyo following its debut in the exhibition catalogue of the 1982 exhibition “Obsession Yayoi Kusama”, and was later acquired by Dr. Takahashi in the late 1990s. Dr. Takahashi recalls showing it to “an influential gallerist”, who praised its importance as Kusama's “last hand-painted work”. Since then, Hat has played a major role in Dr. Takahashi’s adjudication of other Kusama works, specifically in comparing those created solely by the artist and those executed with the assistance of her studio.

Dr. Takahashi notes Hat’s unique technique, particularly the execution of the netting: “The background of the Hat shows a white net set against a red background. However, it is essential to note that the white net is not drawn first in this painting. Kusama drew the red dots first, so the net was the blank space. To Kusama, netting and dotting seem to be different techniques, but in the process of filling the space, they are inversely related, like the image and the ground it sits within. I am unaware of any other examples that present this aesthetic as superbly as this work”.

Hat is at the nexus of Kusama’s early career and the grand dreams still to come. The background’s net patterning echoes the pulsing vitality of Pacific Ocean (1959), also in the collection of Dr. Takahashi. The hat motif links back to the Yayoi Kusama Fashion Company the artist set up in New York in the 1960s, the extravagant apparel she designed for her Happenings of that period, as well as contemporary works including Blue Coat (1965), now held in the collection of the Rose Art Museum, and Flowers—Overcoat (1964), now in the Smithsonian. As for the future, the hat is painted in the solid fishnet style pattern which came to prominence in Kusama’s compositions in the 1980s and 1990s, uniting the two poles of these two periods within one spectacular composition.

It is a timely moment to consider Dr. Takahashi. Until 10 November 2024, 230 works from his personal collection are being presented at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo in a show titled, “A Personal View of Japanese Contemporary Art: the Takahashi Ryutaro Collection”. In a video interview with the exhibition’s curator, Dr. Takahashi described the joy of collecting, and the sense of being a “fellow traveller” with an artwork after living alongside it day after day. After so many decades, he acknowledges the power and weight of what he has brought into being; how a collection, born from him, has reached a scale where it seems to be “driving me or dragging me along.”

The Tokyo exhibition may foreshadow a major new chapter. Dr. Takahashi has hinted at his ultimate aim of opening a permanent space in order to present his collection as a whole. The sale of Hat, he hopes, will “take a step or two towards realising the Ryutaro Takahashi Collection Museum.” Whilst human life is finite, “art”, Dr. Takahashi explains, “lasts for eternity”. This quality of the eternal echoes the infinite nets, dots and mirrors of Kusama’s practice. “And it is, possibly, this very quality of eternity that speaks to us mortals the most.”