Decorator Mario Buatta became renowned for his floral schemes and eye for antiques. As his eclectic collection comes to auction, Olinda Adeane looks back on his life and career.

I n the winter of 1994, Susan Crewe, then editor of English House & Garden, sent me to New York. She wanted a story on anglophile decorator Mario Buatta, who had just completed an apartment for the television anchor Barbara Walters.

We met at an apartment on Park Avenue. I was immediately taken aback by his appearance: sparse strands of hair had been combed across his forehead, while one escaping tendril dangled down in a corkscrew curl, behind his right ear.

I tried hard not to stare, but a few minutes into our interview, Buatta suddenly gave the offending lock a sharp tug, and to my horror, the top of his head seemed to come clean away in his hand.

It was a surreal moment, and then, just as suddenly, there was the Mario Buatta, recognisable from his photographs, beaming and laughing and waving a hairpiece in the air. I realised, with heart-felt relief, that it was all a bizarre but harmless practical joke. Word had not reached me, across the pond, that the famous interior designer was a well-known prankster.

Thirty years later, I remembered that evening with a smile and a frisson when I read of Buatta’s death aged 82, on 15 October 2018, in New York City.

Mario Buatta’s memorial service was held at the Park Avenue Armory. It was arranged, by Hilary Ross, Anne Eisenhower and Emily Evans Eerdmans, to coincide with The Winter Show, a prestigious antiques event chaired by Buatta for many years. Guests invited from the confluent worlds of high society and haute décor gathered to exchange their favorite Mario stories. Buatta had been as much a part of the fabric of their lives as Lee Jofa’s Floral Bouquet, his favourite chintz.

Tears were shed as 90-year-old cabaret star Marilyn Maye sang “Secret O’ Life” by James Taylor: “And since we’re only here for a whil Might as well show some style…”

As they left, each guest was invited to take home a plastic cockroach as their memento mori of their jokester friend. It was the end of an era.

It all began in West Brighton, Staten Island, where Mario and his brother Joseph were raised in a modest English Tudor house built by their grandfather. The Buatta family descended from a long line of stuccadores (specialist plaster workers) who left Sicily in 1860. His father Felix, a violinist and bandleader, had played with famous crooner Rudy Vallée. Their mother Olive was obsessively tidy. They had a fondness for art deco that Buatta disliked. It was in total contrast to the sumptuous colour and joyful clutter that informed his later career.

At the age of 11, he acquired an 18th-century lap desk on Third Avenue for the sum of $12, to be paid for with 50 cent monthly instalments. It was the beginning of a life-long collection.

He enrolled briefly at Cooper Union to study architecture, but decided instead to pursue his nascent passion for interiors; working at B. Altman and Company department store and then for the decorators Rose Cumming and Dorothy Draper. He opened his own design business in 1963, aged 28.

Results from Mario Buatta: Prince of Interiors

The following year he met John Fowler in London, who introduced him to Nancy Lancaster, the owner of the Colefax and Fowler decorating business. It was to be a seminal encounter.

Nancy Lancaster had charm, sophistication, and innate good taste. John Fowler had profound knowledge of historic interiors and an infallible sense of colour. Together they forged a new style that witty Fowler called “an undecorated look of romantic disrepair”, which set a new standard for English Country House décor that endures to this day.

Lancaster’s Mayfair apartment was iconic. Buatta had already glimpsed it in magazines. It represented his ideal. He loved the stunning yellow, glazed wall and very personal and eclectic collection of objects and antiques, seamlessly amalgamated from her past. “England lightened up when your aunt blew into town,” he said years later, on meeting Lancaster’s great-niece and renowned interior designer in her own right, Jane Churchill.

The same could have been said of him, except that Buatta blew back across the Atlantic the other way. Following his trip to England, he was inspired and on a mission to bring the English country house look to the US. Of course, this term was an anachronism, but Buatta adapted the concept to suit the lateral apartment living of New York. He saturated walls in colour and chose flowered fabrics and ceramics that were suggestive of gardens and parks. “It was a dream of England,” says decorator Nicky Haslam. They often saw one another on Buatta’s buying trips to England, taken three times a year, and between 1964 and 1976, when Buatta spent Christmas staying with Fowler at his Gothic hunting lodge in Hampshire.

Buatta wanted to be famous like his contemporary Ralph Lauren, and was delighted when a TV presenter dubbed him the “Prince of Chintz”. It was the trademark he needed. His pranks never failed to capture attention as well: he was a great fan of singer Peggy Lee and would attend every one of her performances accompanied by Mr Zip, a chimpanzee, who had been trained to applaud at the end of each set. Finally, one night, Lee became fed up and tartly announced: “I think it’s past somebody’s bedtime.”

The 1980s were Brideshead years, when everything English and aristocratic was in mode. Buatta launched new product lines, needlepoint, pot pourri and lamps. He favoured frills and ruffles and swags and big blue bows to hang paintings from. Fowler teased him and said that they looked like Minnie Mouse’s ears.

“Mario would have been the first to say that he wasn’t original,” says design historian Emily Evans Eerdmans, “but he brought colour, comfort and beauty to rooms, which he thought of as backdrops for his clients to live their best lives. Not many can say that.”

She collaborated with him on Mario Buatta: Fifty Years of American Interior Decoration. It was the definitive Almanac Buatta, published by Rizzoli in 2013. This splendid tome was so heavy that Buatta joked it had given him a hernia.

“I cannot say exactly how many projects are covered in the book,” says Eerdmans. “He took on as many as 70 new decorating jobs a year and decorated 20 houses for Ann and Charles Johnson alone.”

Over five decades, Buatta’s clientèle included Mariah Carey, Nelson Doubleday, Malcolm Forbes and Billy Joel. His last project – a luxurious riverside duplex – featured in the February 2019 issue of Architectural Digest after his death. Buatta was still on fine form, and the project showed very little compromise towards modernity. “I can’t understand what people see in beige,” he said in one of his last interviews. Recently, and with his usual lucky timing, there has been a backlash against grey minimalism in interiors. Designers like Kathryn Ireland have even been expressing a renewed interest in chintz.

“Buatta brought colour, comfort and beauty to rooms, which he thought of as backdrops for his clients to live their best lives”

A lot of curiosity surrounds the forthcoming sale. For over 30 years nobody had been allowed to visit his apartment, where he lived in eccentric disarray. “His collection was very important and emotional to him. He almost considered it to be his family,” says Eerdmans.

Jane Churchill was one of the last to see it, when she interviewed him for an English television series. “I was astonished,” she says. “In his bedroom, packing cases of books stood waist high. I had to wade through them and if I weren’t wafer thin, I would never have reached the bed.”

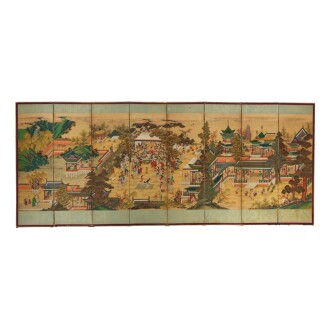

There will be much that is recognisable from his work, as Buatta never used anything in a client’s house that he wouldn’t have wanted himself. “It feels like a private collection and not that of a decorator,” says Dennis Harrington, Sotheby’s vice president of English and European furniture. There is Delftware and Staffordshire, and, of course, there are masses of dog portraits – Buatta referred to them as “ancestral paintings”. There are also some favourite and sentimental pieces: Michael Taylor’s carved dolphin torchières, Prince Albert’s bed from Brighton, and even a pair of Nancy Lancaster’s looking glasses from Haseley Manor. But Jane Churchill may have her eye on those.