M arcel Duchamp was an artist for whom the phrase, "épater la bourgeoisie" might have been a manifesto statement. But he didn’t draw the line at la bourgeoisie. During an explosive career he managed to outrage fellow artists, critics, institutions and patrons, leaving in his wake a legacy as one of the greatest disruptors of 20th century art.

In Prints & Multiples featuring Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q., Sotheby’s presents a rare opportunity to engage with a foundational aspect of Duchamp’s practice in a dynamic auction. This sale includes a thrilling sequence of limited print editions, books and portfolios created by the artist between the early 1930s and mid 1960s, from the collection of Duchamp’s friend, late Swedish artist and sculptor Carl Frederik Reutersward.

How Marcel Duchamp Used the Iconic Mona Lisa to Challenge Artistic Tradition | Sotheby's

Reutersward and Duchamp met for the first time in 1961, at the opening of kinetic art exhibition, Rörelse i Konsten (Art In Motion) at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. Amongst the lots in Prints & Multiples is the screenprint, Cœurs Volants (Fluttering Hearts), which was published on the occasion of Rörelse i Konsten. An edition of 125, this print is an apt souvenir of the initial encounter between the artists, that would lead to a deep and enduring friendship.

Printmaking had been a vital element of Duchamp’s practice since his national service days. It was also in his blood - his maternal grandfather Emile had been an etcher and engraver who had taught the rudiments of the craft to his grandson. In 1905, in lieu of military service, Duchamp spent time in his Rouen hometown working with a local printer, gaining awareness of typesetting and rendering fine art in print.

In the 1920s and 1930s, emerging techniques hitherto unknown in the fine art world, such as collotype printing, afforded Duchamp vast creative potential. He would supervise the entire production process, finding ingenious and creative ways of using the new photomechanical processes, he was thus an innovator here as well as in his art works, both in technique and content.

Duchamp would deliberate over every aspect of production, from paper and inks to typesetting and layouts, whether in the magazines and pamphlets he made for the Surrealists in the 1920s or, from the 1930s onwards, in the beautifully designed portfolios of his own work. Given his antipathy to exhibiting his unconventional work in conventional exhibitions, he found in engraving and printing, a ‘technique of extreme precision’ that allowed him to present contextual documentation around his unique sculptures and readymade installations, in copious detail.

This allowed Duchamp a creatively fulfilling means of contextualising his unorthodox ready-mades and unclassifiable art pieces. For instance, during the summer of 1937, Duchamp created a ‘mini retrospective’ in the form of pochoir reproductions in a suitcase, a sort of 'greatest hits' box set. Initially planned to cover five major works, eventually only Nude Descending A Staircase No. 2 (included here) and The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even were created.

Elsewhere in the sale we find fuller accounts of that infamous work, with 1965’s The Bride (28/30) and The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors Even [The Green Box] (45/300) from 1934. This boxed portfolio features a colour plate and 93 fascinating facsimiles of notes, sketches and photographic documentation.

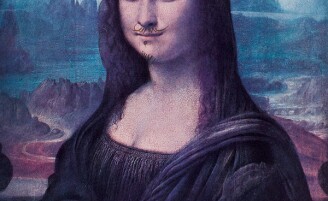

For an artist who had chosen an avowedly non-academic route, preferring ‘ready made’ works to ‘retinal’ painting, printmaking offered a vista of opportunity for Duchamp. In L.H.O.O.Q (September 1964), a print of the Mona Lisa is irreverently embellished with a dainty moustache. The title is a word play — commonly believed to be read 'she has a hot ass'. Duchamp delicately amended this interpretation, however. "In reference to the Mona Lisa," he commented "I also added a sentence of initials on the bottom of that reproduction — L.H.O.O.Q. A loose translation of them would be 'there is fire down below”’.

Not only does this skewer the sacred reputation of da Vinci’s masterpiece, it alludes to Rrose Sélavy — Duchamp’s female alter ego, mirroring the gender-swapping metamorphosis of the moustache. This particular piece has a special resonance as it is a proof aside from the numbered edition that is dedicated to Duchamp’s friend Pierre de Massot. The following year, Duchamp created L.H.O.O.Q. Shaved, as the invitation to a preview of the exhibition Not Seen and/or Less Seen of/By Marcel Duchamp/Rrose Sélavy at Cordier & Ekstrom in New York.

Rrose Sélavy makes another appearance in the sale with Rrose Sélavy (Anthology) and Tiré à 4 épingles — the former (edition 86/515) from 1939 and comprising Duchamp’s beloved puns and word plays book-ended with etchings. It’s accompanied by Tiré à 4 épingles — a series of poems by Pierre de Massot.

Across this collection of innovative and fascinating works, each a painstakingly assembled object of documentation and research, Duchamp’s passion for design and technology is visibly apparent. Anchoring his flights of creativity and fierce dedication to detail, it is here, in his printed artefacts, that science, technology, artistry and ideas converge, guided by the most influential mind of 20th century Western art.