L auded as “a portrayer of dreams and poet of color”, Belarusian artist Marc Chagall developed a unique visual language. Blending Fauvism, Symbolism and Cubism, he created a vivid dreamworld populated by magicians, mermaids, and fair maidens. His bold repertoire of fantastical symbols and bright colours has gained worldwide recognition, largely through the proliferation of his vibrant prints.

Chagall initially experimented with printmaking as a young artist, creating a series of intaglio works to illustrate his autobiography. However he wasn’t fully captivated by the art form until the 1950s, at which point Atelier Mourlot director Fernand Mourlot and expert lithographer Charles Sorlier introduced him to colour lithography. Sorlier, who assisted painter-printmakers Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and Fernand Léger, only met Chagall when the famous artist was 63. Though already established in his career, Chagall gladly sought the young printmaker’s advice. The two became great friends, and the mature student swiftly became the master.

A methodical perfectionist, Chagall approached each lithograph by drawing his composition first in black on stone or zinc. He would then print several proofs, to which he added touches of colour in pastel or wash. If satisfied, Chagall would then proceed to colour testing, often employing Sorlier to help make minute adjustments by hand until he was fully satisfied with each hue. This was a painstaking process, as single lithographs in Chagall’s largest print portfolios contain as many as 25 unique colours.

Chagall’s first major portfolio in colour was the romantic Daphnis et Chloé, issued in 1961. The series of 42 kaleidoscopic lithographs retells the Greek poet Longus’ Arcadian love story. Chagall laboured over the prints for four years, using approximately 1,000 zinc plates, before he allowed esteemed publisher Tériade to release the set. His vibrant colours bring the ancient tale to life, as seen in plate 39, Temple and History of Bacchus (M. 346; C. Bks. 46), wherein the artist’s golden and rosy hues evoke the sumptuousness of the god’s sanctuary (see Lot 5).

His next great masterpiece in colour, Le Cirque (M. 490-527; C. Bks. 68) was published in 1967. Another labour of love, the portfolio of 38 lithographs revisits the artist’s favourite theme: the circus. As a young boy in Vitebsk, Chagall looked forward to seeing acrobats and minstrels perform at local village fairs. In Paris, he was filled with glee to finally be able to attend the Cirque d’Hiver, where he could be found sketching equestrians and unicyclists on a nightly basis. Years later, he revisited his gouaches of the Cirque and decided to reinterpret them as a series of spirited lithographs, accompanied by text (see Lots 21-58). For this project, he developed a range of dusky blues and cheerful yellows that capture the dramatic lights and exuberant atmosphere of the circus ring.

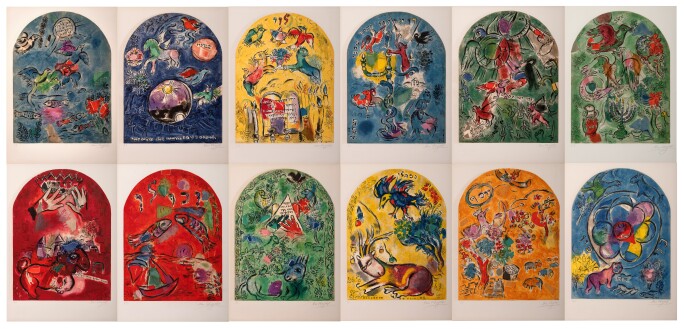

While working on these substantial projects, Chagall simultaneously collaborated with Charles Sorlier on several “afterworks”, which are now some of the artist’s most sought-after editions. Recognising Sorlier’s talent as a colourist, Chagall gave him permission to create lithographs after his unique artworks, from paintings to stained-glass windows. The most sought-after set by Sorlier after Chagall is the glorious Douze maquettes de vitraux pour Jérusalem, or Twelve Maquettes of Stained Glass Windows for Jerusalem (M. CS. 12-23; C. Bks. 57). Inspired by the sublime stained-glass windows Chagall created for the synagogue at the Haddasah Medical Centre, the plates depict Jacob's blessings to his twelve sons and Moses' blessing to the twelve tribes. The complete series captures Chagall’s flair for religious narration, and expertly translates the diaphanous glow of his windows (see Lot 8).