Jack Coulter: From Sound to Vision

And, to get his perspective on his collaboration with Coulter, we also speak to the legendary former Pogues frontman and artist Shane MacGowan himself in a new interview exclusively for Sotheby's.

F rom Joni Mitchell to Blondie, Vivaldi to Alicia Keys, painter Jack Coulter's dramatic abstract works are built on deep synesthesic reactions to songs across a spectrum of musical genres. In a new exhibition, You Can't Change the Music of your Soul at Sotheby's New Bond Street during November 2022, the artist has created a marvellous new series of paintings that pulsate with rhythm, emotion and kinetic energy. Jack spoke to Sotheby's about his new body of works, the music that inspired them, his recent move to London from his home town of Belfast and what it was like to collaborate with the legendary former Pogues frontman Shane MacGowan...

Let’s start at the beginning. If you had to sum up your state of mind right now, a few weeks out from the exhibition, how are you?

I’m feeling great, there’s been an awful lot happening leading up to the show! It’s all very surreal and truly, a dream come true. I’m very focused at the moment - there have been a lot of things in my career that have brought pressure, but with this show, it’s solely excitement. It’s my debut solo exhibition and being an independent artist, that counts for a lot but I’ve pushed myself to my limits creating these works - I didn’t want to have any regrets.

How are you finding London? I understand you’ve recently moved over from Belfast.

I’m in love with London! It’s always had a grand feel and it’s lived up to expectation in every sense. Although I’ve been back and forth with various projects over the years, making the permanent move felt right this year in particular. I didn’t want to come unless things had reached a certain level. It’s important to embrace and be proud of where you’re from and everything that’s happening now is a ripple effect of working in Belfast. That's the place where my dreams were built, London is where they stand.

Can you give us a little background to this show, how this body of work came about?

It all happened organically. After moving to London, I sourced a new studio and finished all the works by September. I painted the two largest, True Colors I & II (Cyndi Lauper) in Belfast, and that felt like a full circle moment. Painting those in my garage where [my career] started was a special thing. Especially given that song and its title, it epitomised everything. In terms of choosing songs and compositions, they’re personal choices but they needed to translate. The selection was eclectic by nature, it ended up being quite a blend of nostalgia and the present. Once the studio sessions began, the choice of music vastly shifted, due to it being quite a momentary process. Most importantly, I wanted to draw from sounds that prescribed a wide range of hues, tones and forms. The musical choices needed to be engaging in an audio-visual sense, as well as being emotionally potent and visually inspiring. It had to be reflective for the viewer.

'When I'm reacting to an orchestral version such as [Joni Mitchell's] "Both Sides Now", the depth of Joni Mitchell’s voice heavily influenced the string sounds. Together they radiated subtle pastel colouring and iridescence against the dark'

Having been reacting to music at such a primal level for years, do you find your visual interpretations are consistent or vary from piece to piece? For example, would a specific tonal or rhythmic element always result in a corresponding colour or gesture?

It can vary quite a lot, as it’s a personal process. My visual interpretations are often dictated by my overall mindset, or emotional state. Still, in an audio-visual sense, the colours are coherent, session to session. In terms of form and structure, there can be drastic changes depending on the song’s overall instrumentation and syncopation. Live versions of a track will also influence the outcome greatly. The most consistent tonal elements arise from strings and orchestral arrangements, they almost represent a monochrome colour chart. Depending on the orchestral composition’s structure, layering and rhythm — the tones rapidly shift from one end of the spectrum to the other.

You can see this visual juxtaposition between Vivaldi's The Four Seasons and the 2000 orchestral re-recording of Both Sides Now by Joni Mitchell. It’s easier to depict standalone strings, as each individual sound is in harmony. When reacting to an orchestral version such as Both Sides Now, the depth of Joni Mitchell’s voice heavily influenced the string sounds. Together they radiated subtle pastel colouring and iridescence against the dark. No matter how small the change in sound is, the original colour can be heavily altered. That’s one of the most difficult elements - trying to portray the subtle changes.

Do you respond to the overall feel, sound and shape of the music or do lyrics [where there are lyrics] have any sort of impact?

Articulating the sounds visually is at the forefront, yet capturing music’s overall feeling is the most vital thing. That’s always my main goal. It’s like listening to a song you’re completely immersed in, you’re unaware of the music in a sense — it’s the feeling that’s resonating. It’s been composed in such a way that it becomes personal. I want my work to reflect that feeling visually. There’s a beautiful word for it called tarab; it means 'the emotions that flow from music'. In terms of the sound, shape and lyrics, I try and let it all come through as one. It really depends on the song. For example, Willow (Taylor Swift) is quite forest-like and tranquil. The track’s colours resonated those tones, it really impacted the painting’s overall arrangement. Titles can even influence the painting, that instant familiarity needs to click. Candle In The Wind represents that, there are elements to it resembling candle-like movements.

Following from that, does the historical and cultural context of a song affect your process? For instance, below, I mention a disco glitterball feel to the Heart of Glass painting, or a sunflower yellow in Vincent. I just wondered if this was something that was in mind when you made these pieces?

Definitely, certain songs already present associated tones. It’s almost storytelling, they allow subtle nods to the song or artist. Depicting the song visually is the main objective, though often it goes beyond that. You can see this in the Heart Of Glass painting, I worked to a remix of the original Blondie track featuring Debbie Harry and Philip Glass. It’s quite a haunting piece due to the track’s instrumentation. I discovered that version from watching The Handmaid’s Tale, many of the choices were found through film and television. I wanted a figurative visual of a shattering heart in it. The piece as a whole is an abstraction, yet once you notice the heart-shaped form, it kind of stays with you. I want each painting to be memorable. Sometimes a defining feature or unique colour scheme helps with that. Vincent [by Don McLean] was similar, the colours prescribed from the track reflected many of those in Starry Night.

When you begin, is there a typical starting point, your usual entry point, on the canvas? How does the work typically assume a direction and formal character?

It’s always momentary, there’s never a pre-conceived notion or idea beforehand. The only constant is saturating the canvas in water, this allows intentional and unintentional movement throughout the process. Everything merges as one even when there’s a prominent mark or line. I can direct paint using this technique, nothing’s permanent during early stages of the painting’s structure. It’s like being able to edit the work, it can take on a life of its own with the use of water. I don’t usually have a starting or entry point, it changes a lot!

Were there any new processes or compositional elements you explored in this body of works that are new to you?

There’s been a new process that’s present in many of the works. It’s something I’ve done for years though never on large-scale pieces.

Typically, how long would each take? Do you work consecutively or concurrently on a number of pieces at a time?

I’ve always painted quick. It depends on the day and scale, sometimes it’s one; sometimes it’s eight or nine. If they are paper works it’s usually way more. Often though when it’s a “dead duck” as Lee Krasner once said, it can take a lot of time to salvage it. I destroy works and leave them outside when they’re goners!

You mix it up in terms of materials - can you talk about how you decide on enamels, acrylics or household paints?

I use everything that’s around me! Those mediums in particular have always been a constant. I’ve never strayed too far away from them, in particularly household paint. It was mainly down to using what was present in my garage as a teenager. I’m always conscious of the medium being used as each has its own function, especially when reacting with water.

What have you been looking at in recent months? Are you absorbed with any artists in particular at the moment and if so, what are you drawing from their works?

It’s mainly been film and music that I’ve been absorbed in this year! In painting, my favourites at the moment have to be Joan Mitchell and Grace Hartigan. They’re always favourites though the list is endless! I’ve found myself engrossed in different artists at various points of my life. For contemporary artists, it’ll always be Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst.

What’s next for you - you seem to be always in the midst of something interesting! What is coming up next?

God knows! Though there are quite a few things in the pipeline. That’s the most exciting thing about being independent, the years are always changing. I can never call what’s going to happen. At this stage, having my debut show at Sotheby’s won’t be topped. It’s the ultimate dream come true. I’ll never be able to fully express my gratitude to those who’ve always supported me, and now to those at Sotheby’s who’ve given me this opportunity. I’ll start crying at the show! I’ve always loved the Helen Frankenthaler quote “There are no rules, that is one thing I say about every medium, every picture . . . that is how art is born, that is how breakthroughs happen. Go against the rules or ignore the rules, that is what invention is about.” I think that says it all!

E arlier this year, Shane MacGowan published a book of drawings and writings, The Eternal Buzz and the Crock of Gold. British art critic Waldemar Januszczak wrote the introduction in which he describes the former Pogues frontman’s art, as being possessed of a ‘demented, wild, fascinating, scabrous kind of energy’.

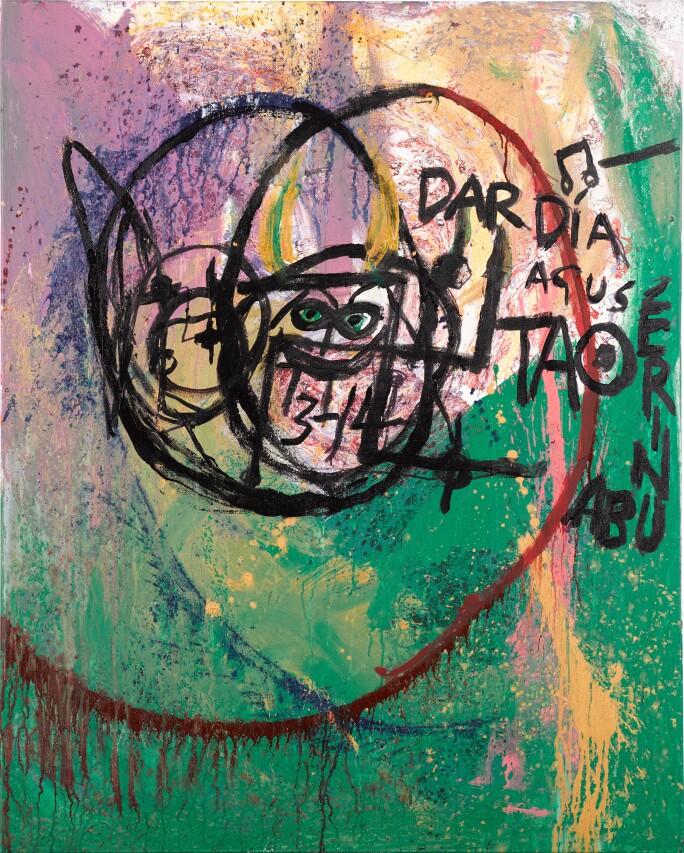

Anyone familiar with the rollicking, stomping music MacGowan made with the seminal Irish punks The Pogues during the 1980s and 1990s would no doubt agree. Today, despite his wild hell-raising days being far behind him, Celtic mercury still surges through MacGowan’s veins, in his art, his writing and ideas. Despite being largely housebound in Dublin, he recently collaborated with Jack Coulter on a painting featured as part of the latter’s new selling exhibition at Sotheby’s this month. Here, in an exclusive conversation for Sotheby’s, with his partner Victoria Clarke, Shane gives us a sense of what was in his mind when he collaborated with Jack on If I Should Fall From Grace With God, the artwork named after the title track of The Pogues’ 1988 gold-certified album.

Shane: The shape of their eyes is the infinity loop, and then they’ve got really intense meditation stares.

Vic: Who?

Shane: The eyes! And then it’s the 3.14, the pi, that goes on forever. They’ve been trying to get to the end of it for years, the Japanese on computers and everything. It’s infinity.

Vic: What else is in it?

Shane: Dear Dia agus Eireann Abu.

Vic: What does that mean?

Shane: For God and Ireland forever.

Vic: And there’s a musical note?

Shane: Yeah. I couldn’t tell you what that is, but it's quite common. A double note, with a bar across. I can't remember what it means.

Vic: What were you thinking about while you were doing it? I know you were listening to Hell’s Ditch from If I Should Fall From Grace With God. Did that come to you while you were listening to it?

Shane: Yes! Because I realised that most of the riffs, or my riffs anyway, me and Jem’s riffs, are like infinite riffs. That’s what a hook is, it’s an infinite riff. You can cut it short now and then to keep them hooked. You give them a verse, and then a long one at the end.

Vic: So, you were listening to that and because it was an infinity riff, you did some infinity symbols.

Shane: Yeah, but I was planning to anyway, but that’s how I fitted it in. Then they looked like eyes, so I made them eyes. They were all mandalas.

Vic: Can you explain what a mandala is, for someone who might not know?

Shane: It’s basically a cross with a circle round it, but there are ones that leave out the cross or leave out the circle. But they usually just have things going in a circular fashion.

Vic: What else is in that picture - fall from grace? That’s about demons, those eyes look like demon’s eyes.

Shane: No, they’re the big eyes of the Tao and God. The Tao that can be named is not the true Tao.

Vic: What is the Tao?

Shane: Well, I can’t tell anybody what it is. It’s the Tao, you must work it out. Like, God is God. There is no mathematical way of expressing God. They think they can do it with infinity, but they can’t. They’ve already hit infinity when it’s 3.14 recurring, which is algebra.

Vic: Did you enjoy doing the painting?

Shane: Yeah!

Vic: What did you enjoy about it?

Shane: It was a creative activity and rewarding in all senses.

Vic: I saw your eyes light up as you did it because you kept thinking of more things to do, you were inspired!

Shane: Yeah! I was.