T he people of the Spanish Empire often spoke of El Dorado — “the Golden One” — a mythic chief of the pre-Hispanic Muisca people of the northern Andes, who, in an initiation rite, caked his skin in gold dust and submerged himself in Lake Guatavita. The legend of El Dorado evolved, as legends do, into an entire city of gold lost to time, the obsession of hundreds of years of fortune-chasing adventurers and conquistadors. Legends are durable. Now “Eldorado” is the name of a narrow jewelers’ storefront in midtown with a thin banner attached to its awning offering “CASH FOR YOUR GOLD.”

Is there another precious metal so culturally precious? Maybe, but none come close to gold’s primacy in the imagination, so tethered to our sense of worth that it persists as the benchmark of economic stability on global indices. We are fiends for it, and our attraction is ancient. We are not so far removed from the Egyptians, who believed gold was the metal of the gods, their skin and bones made of the stuff and their pharaohs buried in gold finery to please them; or the Greeks, who were sure to leave a gold coin with their dead, as a payment to the ferryman. Gold transcended ideologies, illuminating the divine in both Islamic and European manuscripts – an association that carried over to Christian artists, whose baby Jesus and Virgin Mary icons were rendered in tempera and gold leaf, serving as pious deities that would flicker and dance in candlelight. Art presented as a spiritual experience. Gold-laden altarpieces like Giotto di Bondone’s Ognissanti Madonna figure in Kehinde Wiley’s paintings, which are reappropriated in generous applications of gold foil to anoint modern black men and women into the pantheon.

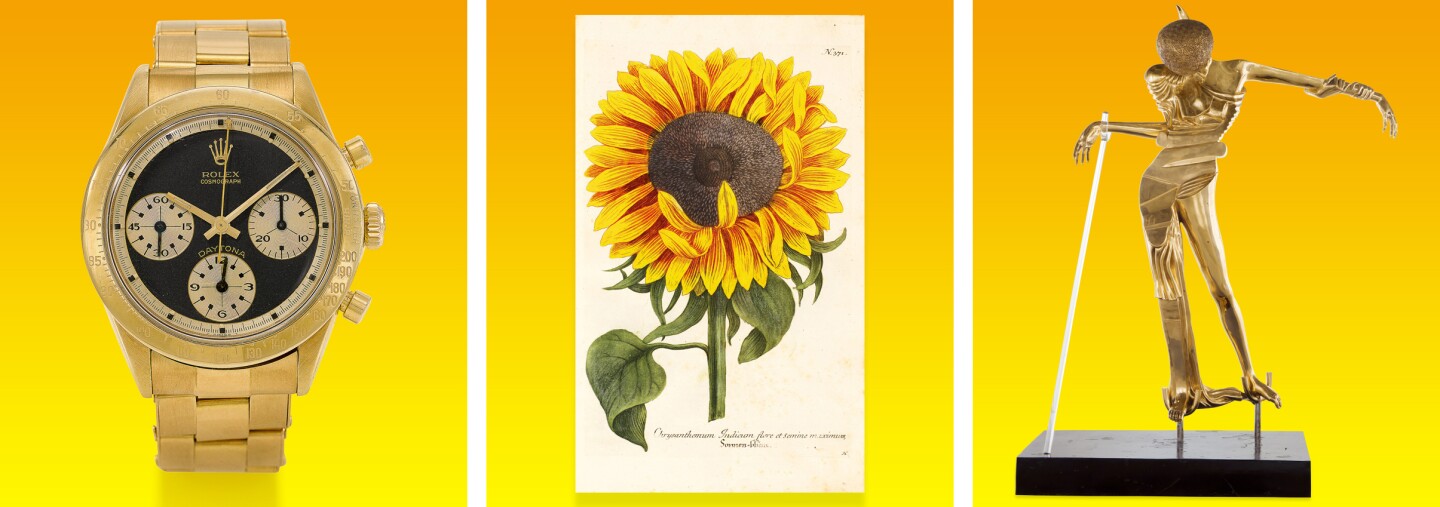

Gold was the surest way into the next life. It still is. There is precious little air between the pawn shops that pock Santa Monica Boulevard and the legacy jewelers that skitter up New York’s luxury spine of Fifth Avenue – save for a marketing budget. The same desire feeds enterprises of all shapes. You can find a hyper-rare Paul Newman Daytona Rolex, with its splendid Deco-informed yellow-gold case and bracelet coming up at auction, but if you miss that, you’re liable to find a half-decent counterfeit being hawked on Canal Street. The medium is the message, and both are universal.

In art and luxury, gold finds common purchase as an immediate signifier of rarity and taste, even if it’s encountered easily enough and easier still slips into flashiness.

In art and luxury, gold finds common purchase as an immediate signifier of rarity and taste, even if it’s encountered easily enough and easier still slips into flashiness. Its chemical appeal is obvious: soft and inert, malleable while remaining durable; it can be melted down, poured and contorted, or hammered out and applied in gossamer foil leaf, at which point it can be used to garnish thousand dollar hamburgers and ingested, completing the loop — nearly. For the full circle effect, consider the Italian conceptualist Piero Manzoni, a real mixer, who in 1961 gleefully terrorized the art world’s self-importance and object fetishization by canning his own excrement, labeling it “Artist’s Shit,” and pricing it at gold’s daily market value (around $37 then; 45 years later, Sotheby’s auctioned one for $120,000), making a work of art that was, inscrutably, worth its weight in gold.

We refer to the “Golden Age” of Dutch artists to designate that period’s nonpareil production and innovation — the ostentatious tablescape still lifes of Jan Davidsz de Heem and Willem Claesz Heda, and the lustrous realism of Rembrandt, Hals and Vermeer. There were more valuable goods in tulip-mad Holland, but none as evocative. More than 200 years later, Klimt draped his heroines in ecstatic folds of gold, as evocative a choice as could be imagined for the son of a gold engraver raised in poverty. In The Kiss, Klimt’s lovers are gripped by passion, the rest of the world fuzzing out into a glittering fugue.

After Marilyn Monroe died in 1962, Warhol screenprinted her disembodied head onto a gilded canvas so that it floated in a sea of gold, subsumed by her gold-lamé halter neck from Gentlemen Prefer Blondes. Warhol anointed her an icon in the canonical fashion, Saint Marilyn of Synthetic Polymer, an American icon spinning in infinity.

Gold demands attention. It jolts the passerby upright. It works this way in the ecstatic impastos of goldenrod and sun-baked earth in Han's Hofmann's Terpsichore, or the steadily vibrating panels of electroformed gold of Rudolf Stingel’s Untitled from 2012. Stingel’s panels incorporate copper and plated nickel, but it reads solid gold to the eye; its surface gouged with scrawled lettering, names and glyphs, as if it were a graffiti-caked wall lifted wholesale and cast it in molten metal – a shrine to the street. It appears like a relic, an anthropological entry salvaged from El Dorado, but its source material is a bit more recent, taken from the participatory installations Stingel showed as part of his 2007 mid-career retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and the Whitney, in which he invited viewers to mark up aluminum-coated boards. He then used the objects as molds, a collective ennobled to the rarefied preserve of the blue-chip artist.

Such is gold’s shapeshifting quality, its ability to both exalt and isolate. It does both in Terry O’Neill’s 1991 portrait of Naomi Campbell; Campbell positively regal, shot against a backdrop of dripping golden kitsch – the kind of gaudy neo-Louis XIV muchness that gets mistaken by insecure real estate egoists for class.

Keynes called gold a “barbarous relic;” its lusty sheen already overdosed. That hasn’t yet ruined our appetites. The cover art for Watch the Throne, the 2011 album from Kanye West and Jay Z, contemporary hip-hop’s highest earning eminences, depicts a gilded, ornate, vaguely religious panel, much like the imagined detail of a modern Maestà. It’s not subtle. Courtesy of the designer Ricardo Tisci, himself partial to a baroque maximalism, the album’s packaging does in fact fold out into a crucifix. It’s a decorative fixture to hang a boast on, egoism as costume jewelry.

One of the finest examples of the form must be Michael Jackson and Bubbles, Jeff Koons’ Pietà, a life-size sculpture in porcelain and gold that suggests a Madonna and child. "If I could be one other living person, it would be Michael Jackson,” he once said. Draping yourself in gold is a good place to start.

Cover illustration by Karen Oliveros.