O ne of the leading lights of London society over the past 40 years, restaurateur Jeremy King was, along with his business partner Chris Corbin, something of a visionary in the capital's hospitality industry.

Corbin & King founded and managed some of London’s most iconic restaurants, including Le Caprice, The Ivy, the Wolseley and Brasserie Zédel on Piccadilly and the Delaunay on the Strand. These restaurants were cherished by the cognoscenti for their characteristic blend of impeccable quality and service, painstaking attention to decor, style and ambiance and an indefinable 'x' factor that welcomed discerning locals, visitors to London and some of the capital's most glamorous diners. With its air of Mitteleuropa places like the Wolseley came to embody a very London sensibility of old and new, tradition and fashion, cosmopolitanism and Britishness.

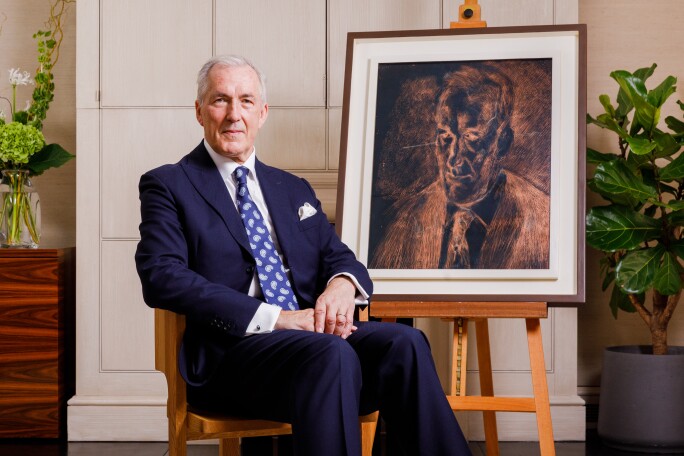

One regular at the Wolseley was Lucian Freud, who loved the place so much, he would show up for a late supper most evenings in the early 2000s. Indulging his loves of seafood, fine wines, stimulating company and endless people-watching, Freud was a perfect guest. Over the years, he became close to the elegant and unassuming King, a quiet friendship which led to him eventually asking King to sit for a portrait. This was followed some years later, in 2011, by an etching. Executed slowly, yet with deadly focus as we'll read, when Freud was in failing health, it brought an extraordinary career to a fitting close.

Sadly, the work, which was initially intended as an etching, was ultimately never used, with Freud’s final chalk marks still visible across the highly worked copper surface

Ahead of this unique work featuring in Sotheby's Contemporary Day Auction, Sotheby's meets Jeremy to talk about the origins and execution of the work, his fond memories of his late friend as well as sharing an exclusive extract from his diary, chronicling his final sittings for Lucian.

What did you know of Lucian before you met him?

I had always collected art and even though I’m fairly old, I’m not old enough to remember when Lucian was particularly affordable. So, I was thrilled when he started coming into Le Caprice in the 1980s - we would see him from time to time - and at The Ivy, so he was always very much part of my world. But it was when we launched the Wolseley in 2003, that I really got to know him.

What do you think drew him to the Wolseley? He was a dedicated regular, by all accounts. His own favourite table and everything

The Wolseley, for him, struck a note because it evoked the Europe that he’d partially known and seen, to a degree in Paris and so on, in the 1950s, and he very quickly started coming there regularly. In fact, if you look at Martin Gayford’s account of sitting for Lucian, he talks about going to the Wolseley after sittings. The restaurant was quite new then and it was always fun when Lucian came because he could be quite mischievous at times. In his book, Martin wrote something along the lines of, ‘I was introduced to Jeremy King, the proprietor…’ - I can’t remember the exact words, but Lucian informed him that I was a black belt karate or judo expert. Which was completely untrue!

That’s quite random!

He just made that up because he was fascinated by people. So, anyway, I started to get to know him, and he was the only person that I would sit with, except my immediate family in the restaurant, because I’m a comparatively old-fashioned restaurateur. But he would often come alone and once he adopted the Wolseley through the next eight years, he would come up to six, sometimes seven times a week for dinner.

What did he like to eat?

Normally, it would be a half pint of prawns, then the fish of the day - which he sometimes ate by hand. And then finishing with an ice cream coupe, with pistachio, hazelnut and almond nougatine ice creams. The Wolseley renamed that dessert Coupe Lucian after his death.

He would come in post-sittings, usually with the current model, and we developed a friendship. I’m the sort of restaurateur who doesn’t assume that I am a friend, but we were very friendly. And he would also utilise me - if he wasn’t enjoying his dinner, or if he had a difficult guest, he would often ask me to join them to defuse it or whatever, which was fun. If he was by himself, I’d join him. He always had good wine, because I encouraged him to bring his own cellar to the restaurant, otherwise he’d never use it. Good wines, from people he’d done things with, like Rothschild or Mouton and so on.

'Lucian was often considered selfish, but in truth he taught me the difference between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ selfish'

I remember phoning him up one evening, because there was a woman - a relation - sitting in the restaurant. She’d come in and said, I’m having dinner with Lucian Freud. We hadn’t heard from him, so she sat and waited, while I phoned him. ‘Oh gosh,' he said. ‘I wondered whether you just didn’t want to see her’ I said. ‘Maybe you’re avoiding her or something?’ He said, he didn’t understand that - he simply wouldn’t have made the arrangement, if he hadn’t wanted to see her. ‘I never do anything unless I really want to do it'. Which was a good lesson. He was very honest about it, he would simply say to people who asked him things, no, I don’t want to. Lucian was often considered selfish, but in truth he taught me the difference between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ selfish.

'We’d sometimes sit in the restaurant together, comfortable without having to say anything.'

He always craved the company of women, but he was very much a solo person, and I was the same - I mean, in terms of being solo! We were both fairly taciturn, neither of us were effusive people, so we could enjoy our time together, whether observing, speaking or singing songs, or just saying nothing. We’d sometimes sit in the restaurant together, comfortable without having to say anything, and that was important to him.

Singing?

Yes, singing! We started singing to each other in the studio. Once at breakfast, when he was with, I think, Catherine Goodman, who was an ex-sitter and painter herself, she asked me, ‘Why have you got sheet music with you?’ I said, ‘Well, because Lucian wants to sing and we wanted to check the lyrics’. He said, ‘Oh, what have you got? What have you got?’ I said, ‘I’ve got Cheek to Cheek, I’ve got a whole load of others’. He said, ‘Great, so you start!’

'We were, at breakfast at Clarke’s and I start singing, Lucian joins in. Also, there was this visiting tech billionaire at the table, completely bemused by the whole thing'

So, there we were, at breakfast at Clarke’s and I start singing, Lucian joins in. Also, there was this visiting tech billionaire, friend of Catherine’s, at the table, completely bemused by the whole thing. Lucian said, we’re going to do the whole repertoire! Where Or When, he liked that one, it’s an interesting lyric. But the interesting thing about him, was his short-term memory was fairly short, but his long-term memory was actually amazing, as he could remember all the lyrics.

So how did the sittings for him come about? Did he suggest that to you fairly early on in your friendship?

I never dreamt that I would actually sit for him, I never even presumed that I would sit for him, until New Year’s Eve, I suppose, it must have been 2005. I’d been down to the RAC - I remember I had a bit of a cold - and I came out of the club and walked up through King’s Street by Christie’s, and in the window was a Lucian painting, Man In A Wicker Chair, the one of Victor Chandler, the bookmaker. And I stood there and thought, how does this happen? Who is the man in the wicker chair and why is he sitting in a wicker chair and what was the reason?

Now as I discovered later, that particular piece, and some of the other paintings he did, came about as he owed money to people, and would barter a painting for a gambling debt. There was a whole range of paintings of Irish bookmakers, which can attest to that! And so, I’m walking up St James's, and I can remember very clearly just crossing the road and stopping in the middle of St James Street and saying to myself - he’s going to ask me to sit.

Wow! A sudden premonition?

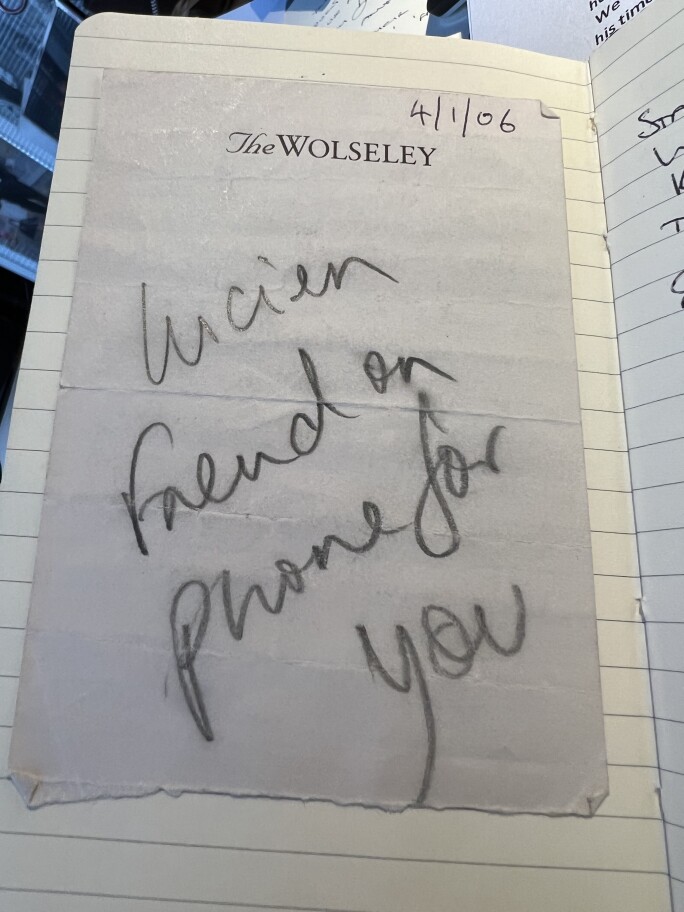

Yes - so, I walked on, thinking - why did you suddenly have this premonition? Or is this just wishful thinking or is it just part of the thought process? I didn’t know. Strangely, just a few days later, I was in the bar at the Wolseley, talking to an acquaintance and the maître d'hôtel comes to me and says, I’ve got a phone call for you.

And they would often do that if they thought that I was stuck. In fact, I wasn’t - my acquaintance was telling me some quite interesting stories about his disastrous Christmas. I said, it’s okay, take the name and I’ll call them back.

The maître d' scribbled a note and passed it over, and it said, ‘Lucian Freud on the phone for you’. I went to the phone, and he said, ‘I’ve been thinking about you a lot, I would like to work from you [Freud typically asked sitters if he could work ‘from’ them]. Would you sit for a portrait?’ And I said, ‘Of course’ - and then nothing happened for a while. We met for breakfast and talked about it further, and then I didn’t hear from him.

I later learned the context to this. It was Susanna Chancellor who is well-documented as having been one of his lovers, with whom Lucian had been having dinner with. He had been saying, ‘I keep thinking about Jeremy,’ and she said ‘Well, that’s because you want to work from him, why don’t you ask him?’ And so he went ahead.

So, we come to the actual process of sitting for him. How was that?

The portrait took two years. I would normally sit two mornings a week, with odd breaks when it wasn’t possible. The etching took longer. That’s because we had to decide from the outset whether I was going to be a morning sitter or an evening sitter [Freud would typically work concurrently on separate projects in his ‘morning’ or ‘evening’ studios]. I had said I’d be a morning sitter, but once that was decided, I didn’t hear from him for a long time. Then one morning, I had woken up not feeling very well, and I get a call saying, can you come straight away and sit? And off I went.

It must have been nerve-wracking, at the outset?

Of course, there was a lot of apprehension. Like, am I going to be any good? Luckily, he always said I was a good sitter because I always adopted the same position and then kept it.

So, we’d work two mornings a week, always starting with breakfast, before going back to the studio. In the early days, I would say, he could work as much as 50 minutes in the hour and then have a break. As time went on, it got less and less, so by the time we were doing the etching, it would often only be ten minutes in the hour. For a long time, he would keep drawing, drawing and drawing, in chalk. If you read Martin Gayford’s book, you will find a terrific evocation of what it was like, to sit for him.

'We talked about his love life. Or weird things - he would talk about Paris and Picasso, and his time with him... He’d go off on diatribes - He’d just tell all these anecdotes'

What would you talk about, during sittings?

We’d talk about his life, or family. We’d talk about one of the happiest times of his life being when he was in Paddington, in a kind of squat, and he did a lot of his best work there. We’d talk a little bit about his grandfather, his brothers who he got on terribly badly with, we would talk about relationships through life and about his schooldays, because he used to get chucked out of schools. He ended up in one school because they allowed him to ride a horse bareback. He could almost be described as feral - and I mean that in a positive way.

We talked about his love life. Or weird things - he would talk about Paris and Picasso and his time with him, about John Richardson and so on. He’d go off on diatribes against Deakin, who, he claimed, used to steal his work and so on. He’d just tell all these anecdotes.

You mentioned that there had been a potentially catastrophic moment when he was preparing the etching…!

Yes - that plate had quite a life! There was one point, when he was well into it, and his studio was incredibly hot. To sit static for a few hours, even with breaks, would make you get terribly soporific. And on this one day, when he left the room, it was boiling, so I went to turn off the radiator and as I came back up, I touched the plate on the easel. He hadn’t secured it and it fell onto the floor with a big crash. So, I picked up the plate and put it back on the easel and - to my horror I saw that it was damaged, and there was this line across the wax. You can imagine, after all this time when he wasn’t initially sure whether he was actually going to do the plate, and now I’ve ruined it. So, when he returned, I fessed up straightaway of course and he said, ‘Oh, that’s okay’, and set about repairing it. You can use liquid wax so that it won’t ultimately affect the plate, but if you look carefully, you can see it there.

Why wasn’t the etching ever finished?

Towards the end, when I would show up to sit, David [Dawson, Freud's assistant] would say, I’m not expecting him to do much, he’s getting very frail. This was a couple of weeks before he died. David said it doesn’t matter whether he does [anymore] or not, we’re going to pull the print because it’s advanced enough. Then, Lucian was using the chalk, or the etching tool - he always used to call it scratching rather than etching - and he picked up the chalk, and being left-handed, while looking at me sitting, as he was standing at the easel, he just goes like this [gestures swiping across to the right].

Then he lifted the chalk clearly over my body and did it again. I didn’t think anything of it until David walked in and went, ‘Oh, fuck!’ I said, ‘What?’ And he said, ‘We can’t print it because he’s changed the intention of the piece. If I allowed it to be printed, it wouldn’t be true to his vision, now that he’s put that [chalk mark] in’.

He had wanted just to put some perspective in, a horizon - I think it was the fireplace or something like that. Then there was a lot of talk as to whether it would go into the Tate or not, but then it was offered up to me, and of course I took it.

DIARY EXTRACT

The first time I went back to sit for Lucian, I wrote:

Thursday, 7 August 2008

“I arrived at Clarke’s at 8.30am, dressed in the same suit and tie worn for the portrait. Lucian didn’t seem to want to finish breakfast, but eventually I found myself retracing the walk to the studio that had been commonplace and now so strange. Once more I absentmindedly wiped my shoes before setting foot on a much dirtier than ever carpet. Everything seemed to be a little more dilapidated, not least the studio anteroom which Lucian is apparently now flooding quite often with his bath. Privately, David confided his fears about Lucian, and I said that he now has another parent to look after and a live-in carer would soon be necessary, otherwise the burden on him would be too great”.

[Lucian was not feeling well at the time and was being given penicillin for a foot infection]

“It takes him ages before he approaches the very large plate and it’s strange to see a chair beside him with only chalks and cork-handled etching tools, rather than more familiar paints and brushes. He says he has no idea what he’s going to do, and I ask whether the same suit and tie and position is a good starting point. No response. He’s preoccupied. Then he wants to talk about past loves, both of ours, as well as those of his brothers. He shows me an interview with his brother, Stephen.

Then suddenly, he approaches the plate. He keeps recoiling from it and even seems driven out of the room by it. And then, he says: ‘I wonder - I think. Good - I hope - I do’. He says all these things: ‘You know - so, I wonder. I think - good - I hope - I do’. Totally absorbed.

And this is the soundtrack to the sitting and without warning, and with a lunge, the first line is drawn in chalk. ‘I hope - I wonder - I do,’ he says. And then the breaks continue but with me implicitly forbidden to move, with no allowance that I might need to stretch. There was a sense of purpose we must unite on. Lucian reveals that he’s only going to do my head.

Breaks are spent reminiscing about his mother and how, following her attempted suicide after his father died, he worked a lot from her. His father hated Lucian’s work. Was this jealousy? And despite him having allowed Lucian to go to art school - his father was an artist manqué - after all, it's fascinating, the depth of detail in Lucian’s long-term memory, but the short-term is a disaster.

During one of the breaks, I asked whether the small canvases on the fireplace with their faces turned to the wall were the same that had laid untouched since my portrait-sitting, two years before. He turned over a very familiar one and started to hack at it with a palette knife, determined to destroy.

‘It’s not like I think I’m about to die,’ he said. ‘But I don’t want David to have to make difficult decisions.’ And as he struggled with the destruction, I offered to help and found myself ripping up what would now be a coveted canvas worth, what, a million? More?

He said, ‘It’s not that it’s bad - it’s just not good enough.’ And that was the typical day in the life of the artist.