1. The Bengal School grew out of swadeshi.

In the early part of the 20th century, Indian nationalist leaders promoted the concept of swadeshi, a movement of self-reliance in the face of British colonization that was specifically effective in the province of Bengal. Swadeshi called for social, cultural, political – and most ardently economic – reforms that would break India from the clutches of British rule. Boycotts of British manufacturers were organized in favor of domestic and local products, which would invigorate Indian industry; cultural movements were to dispose of British or Western literature and visual arts, and to produce works of uniquely Indian qualities, turning to Hindu themes and ancient Indian painting styles.

2. The Bengal School was a form of resistance that gave rise to Indian nationalism.

During the British Raj, when the British crown ruled the Indian subcontinent from 1858 to 1947, traditional Indian painting conventions and styles had fallen out of popularity, largely because they did not appeal to the tastes of British collectors. In addition to the European painting techniques and subjects that were taught in artistic academies, Company Paintings were widely promoted, which catered to British sensibilities. Company Paintings presented Indian subjects of indigenous plant life or traditional garb and rituals, through both the European gaze and conventions of painting. Rather than celebrating Indian cultural traditions, it simplified them into exotica. The Bengal School arose to counteract such imagery, by turning to Mughal influences, and Rajasthani and Pahari styles that presented elegant scenes of distinctly Indian traditions and daily life.

3. There were contemporary British supporters of the Bengal School.

Although the Bengal School was a direct refusal of British artistic traditions, one of its major founders was Ernest Binfield Havell, an English art historian, teacher, arts administrator, and author. Havell urged his students to turn to Mughal miniatures as influence rather than British models of production. While principal of the Government School of Art in Calcutta, Havell helped founding artists of the Bengal School such as Abanindranath Tagore and his sister Sunayani Devi fully develop the tenets and style of the movement and promote its dissemination through educational systems.

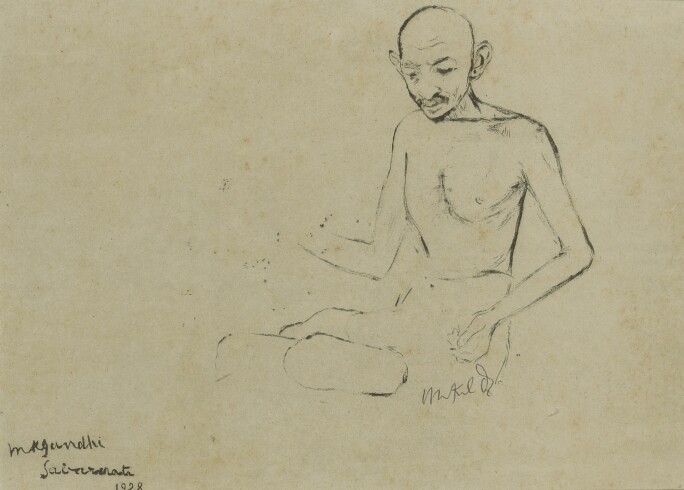

4. Bengal School Artist Nandalal Bose shared a special relationship with Gandhi.

Nandalal Bose, pupil of the Bengal School’s leader Abanindranath Tagore, became one of the movement’s major artists. Exasperated by the British treatment of Indian painting traditions, history, and artists, Bose turned to swadeshi notions of developing a distinctively Indian modern art. He turned to the murals of Ajanta, and produced scenes from Indian mythology and contemporary daily village life. In the 1920s and 30s, he developed a friendship and professional relationship with Gandhi, who often invited him to produce works for political pavilions. Bose commemorated Gandhi’s 1930 twenty-six day Dandi March with a series of sketches presenting him as a humble but strong hero using expressive line work. These images of Gandhi contributed to the development of twentieth century Indian modernism, identity, and nationalism.

5. Asit Kumar Haldar was a major artist of the Bengal Renaissance.

Asit Kumar Haldar was the nephew of Rabindranath Tagore, major Bengal poet, musician, and artist. He studied painting under Jadu Pal and Bakkeswar Pal, two leading Bengal artists, and joined Nandalal Bose to document the Ajanta cave paintings and frescoes from 1909 to 1911. Haldar’s works synthesize Buddhist art with Indian history through a sense of idealism. He was the first Indian artist to be appointed as the principal of a Government Art School, and was the first Indian to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts, London, in 1934. In addition to his artistic production and poetry, Haldar, like his fellow artists of the Bengal Art School, committed his life to social reforms and educational programs that would build a sense of Indian nationalism for contemporary and future generations.