T he museum, unique in its focus on a singular medium, holds a remarkable collection of over 50,000 objects drawn from 35 centuries of glassmaking.

At the Corning, a diverse collection of glass objects and artworks - from ancient functional objects such as mirrors and tableware to the most imaginative contemporary art sculptures - is presented in chronological fashion across dozens of galleries; the Museum tells the history of a medium, all too often overlooked, and highlights the fact that glass art has played a critical role in the development of several art styles, schools, and periods. Far from being a niche field, at the Corning, glass takes center stage.

The Corning Museum of Glass was founded in 1951 to serve as an educational institution sponsored by Corning Glass Works, one of the preeminent and longest-standing glass companies in the United States, now based across the street in the town that shares its name - Corning, New York. Despite its original business affiliation, the museum was established as a non-profit; it was intended to preserve and document an already significant collection of glass artwork owned by the company, with the intention of adding more in the years to come.

The museum opened its doors to the public and launched with a strong holding of 2,000 objects along with a rich research library of scholarly and archival material dedicated to the history of glass, glass art, and the glass industry. After several decades of successfully operating as a museum and expanding its collection, the Corning Museum of Glass opened a studio in the early 1990s. Today, the Studio provides opportunities for visitors to learn glassblowing and coldworking techniques in a state-of-the-art teaching facility; hour-long, day-long and even multi-week classes are available to advanced practitioners and beginners of all ages. An active hub for all things related to the fine art of glassmaking, the Studio also hosts artist residencies; in this way, the Corning Museum also functions as an incubator for artistic talent, a place for both study and creation. Resident artists are able to study 35 centuries of glass, learn from the archives of the museum and library, and create their own masterpieces in the adjacent studio workshops.

Sotheby's Museum Network visited Corning to take a closer look at the Corning Museum's unparalleled collection of glass art, tracing the fascinating and quickly evolving chronology of glassmaking across 3,500 years - from the valleys of Ancient Egypt to the studios of artists today.

The story of glass, like the exhibition galleries, begins with nature; after all, glass is an organic form created through naturally occurring events. According to the Corning Museum, glass is formed when a molten material cools so quickly that a crystalline structure does not arrange itself. As a result, glass can be found in the nature when sand or rocks experience significant temperature changes; when they are heated rapidly and then proceed to cool rapidly as well.

Obsidian is created from molten rock; fulgurites are produced when lighting strikes sand. The museum's collection contains a small but important holding of naturally-created glass pieces, providing a scientific foundation to the visitor's understanding of the evolution of the art form.

35 Centuries of Glass Making at the Corning Museum

Ancient Roman Glass

One of the most innovative periods in the history of glassmaking took place between the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE in the Mediterranean region. This time of ingenuity was directly related to the expansion of the Roman Empire, as the economy improved, new scientific innovations and technologies were acquired from occupied territories, and Roman craftsmen significantly advanced their techniques.

The novel concept of inflating glass with a pipe (glass blowing) now allowed makers to revolutionize the appearance of glass creations. Glass mosaics held up in popularity while also being joined by new practices as glass could, for the first time, be molded into nearly any form. As a result, glass became a core material of ancient decorative arts. Around this time, glass began being sold throughout the Mediterranean and northern Europe in the forms of drinking cups and other dishware, complete with designs created with coldworking techniques. The floodgates for creativity had opened as glass could be painted, gilded, and encased with layers of color.

Glass in the Islamic World

When the Roman Empire fell in 476 AD, the economic instability of the Mediterranean lead to a stagnant period in glass innovation in the region. Yet, this downturn in production did not impact outside empires. The expansive Muslim territories, which grew considerably throughout the 7th century, fostered a second wave of growth in glassmaking and ultimately lead to several technological advances, including the invention of stained glass. Finally, in the 10th and 11th centuries, glassmaking reached new heights in decorative forms and trade success, which ultimately lead to the resurgence of the industry in Europe as well.

The Rise of Venetian Glass

The famed Murano glass industry first began during the Venetian Renaissance. Spread throughout Europe, glass was produced in glasshouses for daily usage. However in Venice, the luxury glass industry was established on the island of Murano beginning in the 15th century. Venetian glass makers developed cristallo, a colorless blown glass that took on the appearance of crystal. The complexity of glassmaking grew even further; filigree glass was invented in the 16th century, a new glass blowing method that utilized rods to inscribe intricate designs in various colors on vessels. Venetian glass is also well known for its use of calcedonio, an artistic technique that uses metal oxides to form marbled patterns similar to opal and agate - rare and expensive natural stones that man-made glass could now replicate for the luxury market.

Asian Glass

Across Asia, glass products were created for various purposes. In early Japan, glassware often held sacred objects, similar to Christian reliquaries. Raw material for Asian glassware came primarily from China; Japanese makers and buyers especially favored a blue glass called Ruri which appeared to have the same color properties as the stone lapis lazuli, also a highly coveted luxury good, often traded along the Silk Road.

Later in 1650, Japanese glasshouses became more prolific in the range of their creations, producing everything from ornate vases to household game pieces. In 1696, the Qing Dynasty emperor created the Imperial Palace Workshops in Beijing, supervised by Jesuit missionaries to China. Here, glass was created to once again imitate a luxury good - this time, porcelain. Porcelain-styled glassware was often shallow and thin for easy portability along Asia's dominant trade routes as well as being carved, painted, or enameled like the porcelain ware it echoed.

Glass in Early America

The first successful glass company in America was founded in 1739 by Caspar Wistar in what was then the British colonies, now southern New Jersey. In fact, glassmaking is largely considered to by America's first industry; the first workshop was founded as early as 1608 in Jamestown, Virginia. Early American glass is known most for glass pressing, a technique and technology in which patterns and decorations could be molded into the glass much like a template or stamp. Industrialized and easily disseminated, early American glassware was also more affordable, meaning middle class families could purchase it for daily use. At this critical point in history, glass enters the mainstream and becomes a more readily accessible object, albeit still largely associated as a luxury good and with the upper class.

19th Century European Glass

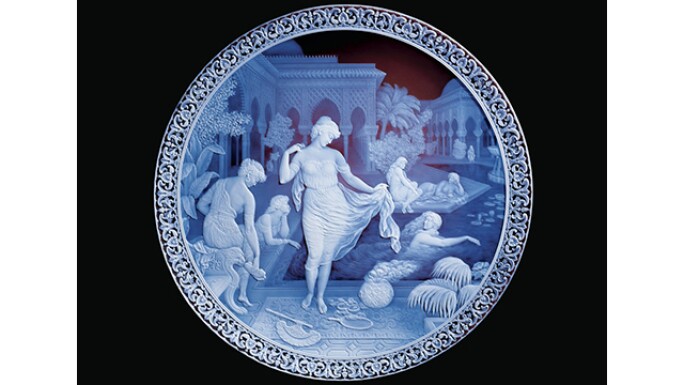

At the turn of the century and at the height of the Industrial Revolution, economic stability grew in Europe and so did the middle class. Glass makers were able to take advantage of the boom by using steam to power cutting wheels. This process reduced costs and made production more efficient. This period is best represented by objects from the British Arts and Crafts Movement, in which designers and artisans emphasized aesthetics over functionality and started creating delicate, fantastical and elaborate products such as this Thomas Webb and Sons' plate - Moorish Bathers - from the late 19th century.

Art Deco

The Art Deco movement is perhaps the perfect example of the modern glass era. Here, in the first decades of the 20th century, artists throughout Europe and the United States placed increasing stylistic emphasis on the uniqueness of an object as well as its public accessibility - design appeared in not only personal objects but on public buildings as well. Here, the decorative and the manufacture merge, resulting in plentiful original and stylish works of art that are nonetheless accessible and more affordable to a larger audience. This can be witnessed in several Art Deco works in the Museum's collection, such as this Cerebres vase from 1938.

The Studio Glass Movement

Quite different from the concepts behind the Art Deco movement is the Studio Glass movement, begun in 1962 by two American artists. Proponents of this school of thought sought to move glass making from the industrial factories of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and into individual studios. Artworks created during the 1960s and 1970s were not, as a result, pure emblems of functionality; rather, the studio artworks were highly if not purely art in their own right. Emblematic works of this period can better be described as glass sculptures; without a clear function or purpose beyond delighting the viewer, they are art in its purest form. Despite the focus on creativity and aesthetics over functionality, Studio Glass Movement artists still looked to the past; they employed historic methods of glass making such as blown glass, cold glass, and stained glass techniques that are difficult to replicate on any assembly line and hark back to pre-industrial times.

Contemporary Art

Neither a single trend nor one theme influences the whole of contemporary glass making today. Artists are inspired by both the functionality of the material and the way in which an artist can push design boundaries in the studio. In addition to technique, the conception of glass art is now often informed by the artist’s personal and collective experiences; art may be installed in either public or private spaces.

Above, the contemporary artwork Virtue in Blue explores the idea of sustainable energy; the artist Jeroen Verhoeven formed a chandelier composed of glass-shaped butterflies. The butterflies are shaped from the glass material that produces solar panels, in effect, the chandelier can be illuminated from the power of sunshine alone.