The late, great collector Ginny Williams transformed US institutions with her pioneering support for – and friendship with – leading women artists. More than 450 works from her celebrated collection are being sold in a series of sales throughout 2020, beginning with the dedicated evening auction which realized $65.5 million in June.

I

n 2011, Helen Frankenthaler’s Royal Fireworks, 1975, sold for $818,500, setting a new world auction record. The luminous canvas expanse is dominated by a rolling passage of subtly-modelled sunset orange, which announces itself repeatedly, like shifting horizon lines. It at once suggests a landscape and a meditation. It is a little like a prayer.

Royal Fireworks was purchased by Ginny Williams, an unorthodox, wry local collector and gallerist who famously never lost her Virginia drawl, even after six decades spent living in Denver. (In photographs, her features announce themselves like a New Yorker portrait: glasses first, then matchstick red hair.) She opened her namesake gallery in the 1980s – at 299 Fillmore Street in Denver’s Cherry Creek North – housed within a long, inky mid-century structure designed by Richard Crowther.

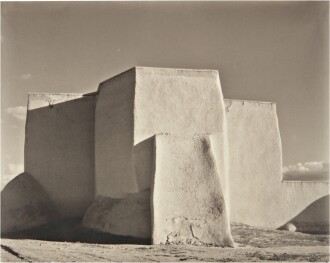

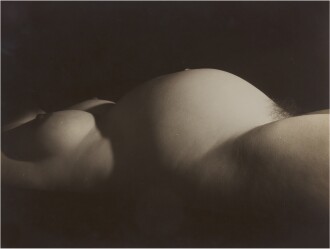

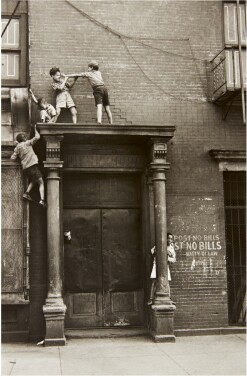

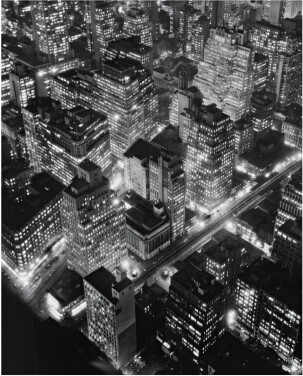

Spotlight on Female Photographers

From the outset, both the gallery’s œuvre and Williams’s private collection were dominated by photography. Having completed her masters in art history at the now-defunct Colorado Women’s College, she found herself ravenous for classically figurative images. But she soon expanded her curatorial focus, amassing early and iconic works from female Modernists across categories and mediums, in particular abstract painters of the 1950s and 60s. Especially prominent was Louise Bourgeois, for whom Williams spent a decent chunk of life as a patron and close confidante; Williams amassed over 40 of the artist’s sculptures and works on paper, spanning more than four decades. It remains the world’s largest privately-held collection.

“She often had a personal relationship with artists she collected.”

There was the 11ft-tall Spider, 1996 – perhaps the most remarkable insect in America’s art-historical canon – completed by the artist in her mid-80s (“spiders are helpful and protective, just like my mother,” Bourgeois said in a 2002 profile). Another seminal Bourgeois form, Observer, 1947–49 – part of a series of anthropomorphic experiments in plastic, then bronze – was quietly rousing, an elongated abstraction that spectators might address, face to not-quite-face, like a person they knew. “Ginny had the sculpture at the base of her stairway in her big glass house in Denver,” remembers Elizabeth Webb, contemporary art specialist at Sotheby’s. “It too was an observer, looking out on all the other works... It remained in that spot for much of its time in Ginny’s collection.” “She often had a personal relationship with artists she collected,” says Amy Cappellazzo, chairman of Sotheby’s fine art division.

“She would really pull into their work hard. She would want multiple examples. It wasn’t usually enough to just have one. She was a real cowgirl, like an original cowgirl. So it didn’t matter what anyone else thought.” Williams had a knack for understanding which artists really mattered, long before anyone else was willing to: Agnes Martin, Joan Mitchell, Alice Neel, Lee Krasner. She bought images by Diane Arbus, Tina Modotti, Ruth Bernhard and Dorothea Lange. Her appreciation for Frankenthaler, meanwhile, is summarised in the artist’s own words: “I wasn’t looking at nature or seascape but the drawing within nature – just as the sun or moon might be about circles or light and dark,” she said of Ocean Drive West #1, 1974, a rhythmic and hyper-saturated painting like Royal Fireworks, produced on the coastline of Connecticut. Ginny Williams knew that a Frankenthaler painting could be a poem, a portal.

Williams’s vision was not limited to her own collection. One of her longest relationships was with the Denver Art Museum, where the Bourgeois spider perched after she loaned it there in 2006. At the same time, she joined the museum’s board of trustees, and began to assemble a blue-chip collection specifically as a gift to them – think Sandy Skoglund and Thomas Ruff.

“She was a real cowgirl, like an original cowgirl. So it didn’t matter what anyone else thought.”

She was also on the Guggenheim board, as well as the board of the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC. At both institutions, she worked shrewdly to feminise their canons, entering the gaping spaces where women weren’t. “I was at the Guggenheim Museum in the 1990s and early 2000s,” recalls Anthony Calnek, a former deputy director. “That’s exactly the time Ginny Williams was very close to the museum. She was a member of our leading collectors board. It was really because of her that the museum started acquiring works by important women artists like Louise Bourgeois, Ann Hamilton and early works by Cindy Sherman and Roni Horn.”

Sometime in the mid-1990s, Williams’s own gallery shifted from a regular exhibition schedule to appointment only, more or less shuttering to the general public. Her legacy, however, continues to be felt in US collections today. “A collection should function as a fingerprint,” Abigail Goodman told Frieze a few years back. Williams knew that already. Hers was all fingers and toes.

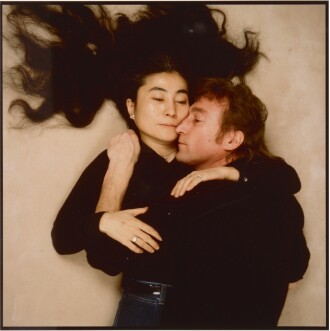

Lead image: Ginny Williams, flanked by LA gallerist Shoshana Wayne and artists Kiki Smith and Bruce Nauman.