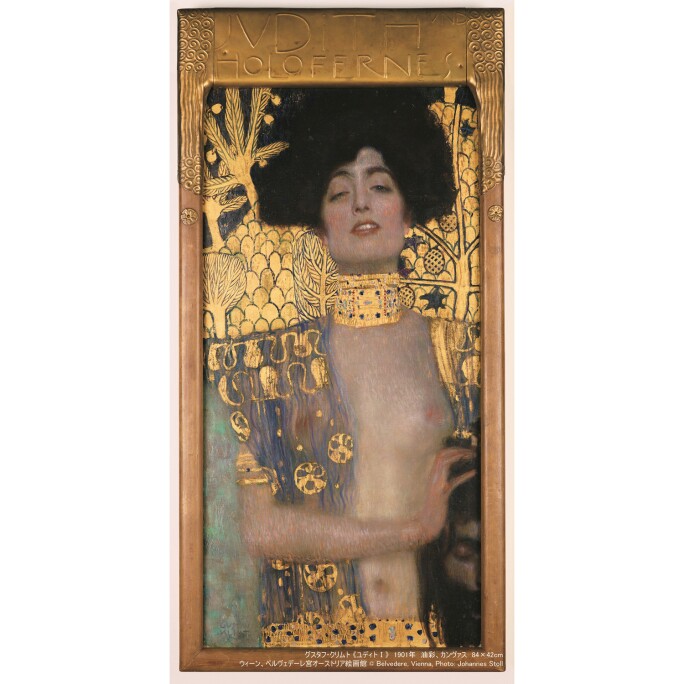

For more than three months now, images of Klimt’s Judith I have decorated the public spaces of Tokyo. Like many of his works, Judith I exudes eroticism, staring down at the viewers with her dark, sensual eyes and smiling contently as she caresses a dead man’s head. It is a powerful work painted in oil and gold leaf, which will be on display at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum until July 10. Alternatively, NACT’s poster highlights the portrait of Emilie Flöge from 1902, depicting a 28-year-old Emilie in clothing ornamented with spirals, gold squares, and dots— exuding the radical and free spirit which defined an artistic alternative to the then-dominant Wiener Werkstätte design.

Born in 1862, Klimt studied architectural painting at the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts from 1876 until 1883. In 1897, Klimt became one of the founding members of the Vienna Secession, a group that aimed to create an independent art scene that promoted young artists and introduced works by foreign artists. Many young artists during this period had protested against academic orthodoxy and sought alternative artistic expressions. On the other hand, Klimt, influenced by his admiration for Academic history painter Hans Makart, embraced these traditional rules at first. This style culminated in a series of decorative paintings, including a ceiling painting for the Burgtheater in Vienna, composed together with his brother, Ernst, and their friend Franz Matsch. However, after the death of his father and brother, Klimt began to search for a new personal style.

As noted by many historians, Japanese art was first introduced to Viennese society by Klimt and the Secessionists through their sixth exhibition, which devoted entirely to its aesthetics. Klimt was an avid collector of East Asian art objects, for example, woodcuts, Noh masks, ceramics, and textile designs. Many of these objects inspired his works, e.g. Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907), Portrait of Eugenia Primavesi (1913/14), and Baby (Cradle) (1917/18). Japanese art as a whole is graphic, ornamental, linear and planar. These design principles greatly influenced Klimt’s approach to drawing and became an integral part of his style.

Klimt particularly admired the Rinpa School, one of the major historical schools of Japanese painting. In the late 17th century, brothers Korin and Kenzan Ogata perfected this style in their depictions of nature, painted in vibrant colors and using various techniques in ornamentation such as gold leaves. Klimt’s portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer from 1907 is strongly enhanced with ornamentations through the use of gold leaf. The portrait itself has similarities in structure and detail to Japanese gold lacquer ware.

Around 1909 Klimt’s oeuvre saw a change, as his works during this period took a subtler tone in the ornamentation. His enchantment with Japanese art was by no means a passing phase, as its influence runs strongly through his later works. Two paintings on show, Portrait of Eugenia Primavesi (1913/14), and Baby (Cradle) (1917/18), belong to this later period. Like many of his works, the paintings have a pyramidal composition, while the vibrant colors and ornamentation are tastefully restrained. The Japanese fabric designs which recur in his other paintings are used as figural backgrounds.

In 1918, Klimt suffered a stroke and soon after contracted pneumonia, which both contributed to his death. He left many paintings unfinished. During his lifetime, Klimt never actually set foot in Japan. Today, the two exhibitions converging in Tokyo will be the most extensive displays of the artist’s work ever in the country, and in its full array offers color and breadth to Klimt’s practice and reinvention of styles.

The exhibition “Gustav Klimt: Vienna-Japan 1900” at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum will be held until July 10, 2019. “Vienna on the Path to Modernism” at the National Art Center, Tokyo, will be held until August 5, 2019.