Ahead of the Contemporary Art Evening Auction at Sotheby's this week, Alastair Smart charts the rise and rise of Gerhard Richter – who holds the current record price for a work sold by a living European artist...

Few artists illuminate a sales calendar quite like Gerhard Richter. In Feburary 2015, his abstract painting Abstraktes Bild (599) fetched £30.4 million ($46.3 million) at Sotheby's in London, making it the second-most expensive work by a living artist ever sold at auction – after Jeff Koons's Balloon Dog (Orange). Two years earlier, his cityscape of Milan, Domplatz Mailand, had sold for £24.4 million ($37.1 million); while the year before that, another abstract, Abstraktes Bild (809-4), sold for £21.3 million ($34.2 million). The world’s very top collectors compete for Richter’s canvases; not bad for an artist who insists he has little interest in the price of his paintings and says the art market is "as incomprehensible (to him) as Chinese physics".

What is it about Richter, though, that prompts such coveting? It certainly wasn’t always this way. Born in Dresden in 1932, he plugged away for decades without recognition, staying loyal to the medium of painting while others were increasingly turning their back on it (for video, installations and conceptual art). Avoiding a signature style, he experimented with several genres: including portraiture and still-life as a figurative painter, and including colour charts and monochromes as an abstract one.

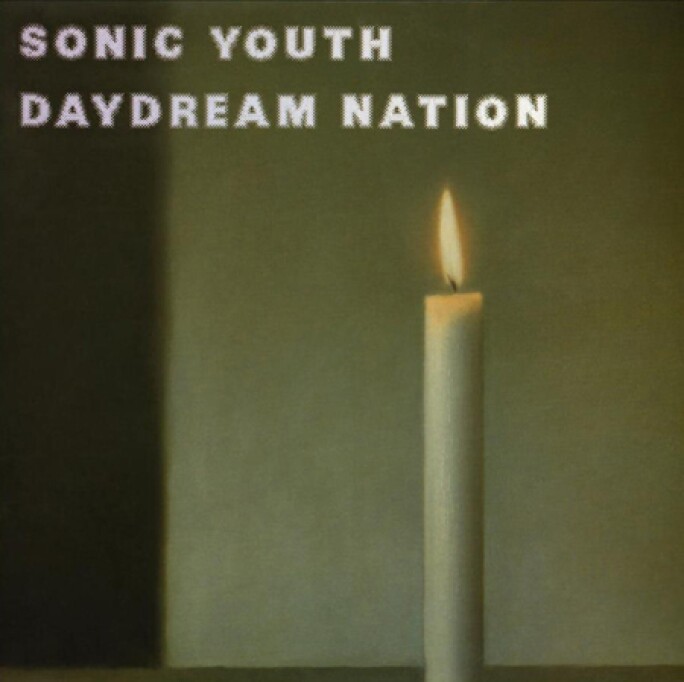

In time, he developed something of a cult following, his painting Kerze appearing on the cover of rock band Sonic Youth's album Daydream Nation, for instance. There was also a growing curatorial appreciation of his talents. In 1995, the Museum of Modern Art, in New York, bought 18 October 1977, his suite of 15 paintings depicting the grim demise of Germany's Baader-Meinhof extremist group. For many, this marked the turning point in his career; it was followed by a major retrospective at the same institution six years later.

After which, broader popularity developed. People saw that Richter was prepared to tackle history head-on, particularly the chequered recent one of his homeland. As well as the Baader-Meinhofs, the Nazi era has been a regular source of inspiration: in 2014's Birkenau series, Richter painted over the reproduction of four photographs covertly taken by a prisoner at the eponymous concentration camp. He has also tackled the subject of 9/11, with his painting September.

It wasn’t long before the market followed where museums and the public had led. His prices soared – though, interestingly, it is Richter’s large abstracts of the Eighties and early Nineties that tend to attract the highest bids. Finished by dragging a squeegee across the canvas, these works are easily identifiable as Richters and – eschewing dark moments of history for bright riots of colour – have universal appeal. They’ve become status symbols for collectors worldwide.

Richter's prices weren't much affected by the global financial crash: in the worst year of the crisis, 2008, five of his works sold for more than $10 million. To give further sense of Richter's commercial ascent, it's worth noting that in 1999, the time before last that it appeared at auction, Abstraktes Bild (599) sold for $607,000.

Now 84, and following his highly successful retrospective, Panorama – which toured London's Tate Modern, Berlin's Neue Nationalgalerie and Paris's Pompidou Centre in 2011/12 – Richter is now revered as one of art's senior statesmen. Indeed, since the death of Lucian Freud and Cy Twombly, he has gained a moniker that, you might say, is worth as much as any multi-million-pound canvas: that of ''the world's greatest living painter''.

MAIN IMAGE, GERHARD RICHTER, GARTEN, 1982. ESTIMATE £3,000,000–4,000,000.