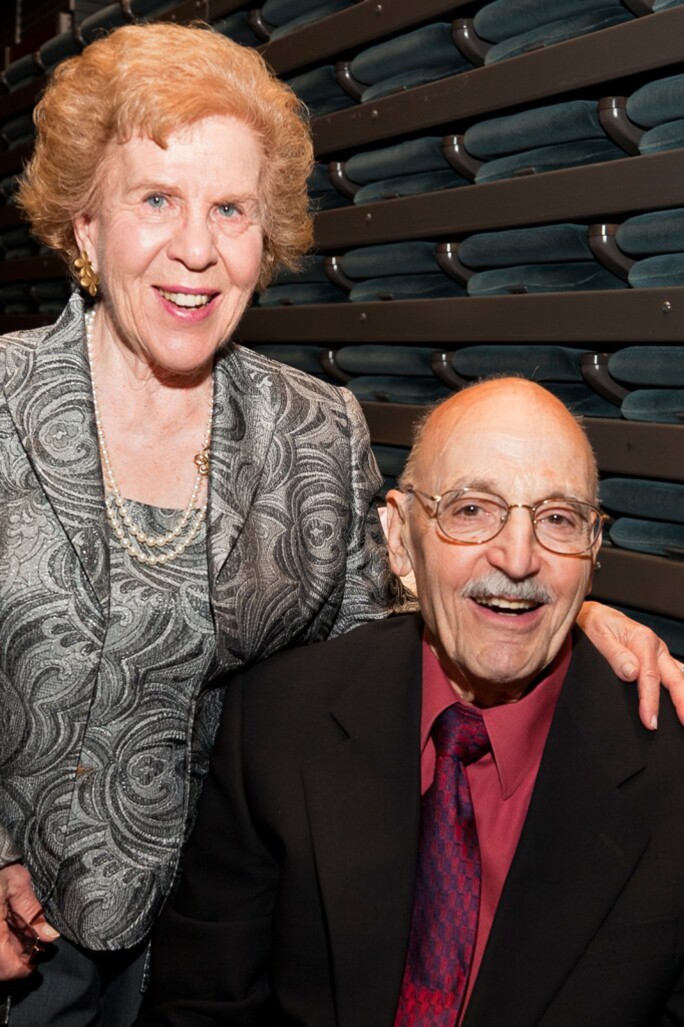

If anyone had asserted at Micki and Jay Doros’ wedding in 1949 that the couple would eventually become iconic figures in the world of antique glass, as well as assembling two world-class collections during their 69-year marriage, that person would have been considered meshuga. Both first-generation Americans, raised during the depths of the Great Depression and lacking any formal art background, training or education, it is practically inconceivable that my parents would become widely recognized, and admired, experts in the esoteric field of collectible glass. Yet, during 55 years of study, patience, and buying, all with unquenchable dedication, that is exactly what happened.

The relationship between Micki and Jay epitomizes the expression that “opposites attract.” Mom was born in Newark, New Jersey in 1927 and was a bit of a tomboy growing up. Named by her parents Mildred (which she always disliked and legally changed later in life), she acquired her nickname after playing baseball with boys who likened her catching style to Mickey Cochran, a then-famous player for the Detroit Tigers.

She attended Weequahic High School in Newark, a school described in detail by Philip Roth, who grew up on the same block as Micki. She graduated in 1945 and enrolled at Paine Hall, a tech school in New York City, where she trained to be a hospital lab technician. Upon graduating in 1947, she got a job in a Newark hospital where she was hazed on her first day of work. As Micki told it, a doctor asked her to draw blood from a patient and, after a few futile attempts, Mom realized that the so-called patient was actually a corpse. It was about that time when she met shy, socially awkward but handsome and exceedingly intelligent Jay Doros at a Hadassah dance in Newark.

My father was born in 1926 and raised in Bayonne, New Jersey, but his happiest days were the summers he spent in Free Acres, a 75-acre enclave in Berkeley Heights, New Jersey, founded on the principles of Henry George. The Doros home there was rather ramshackle and the family struggled during the Depression, but Jay loved Free Acres. He had numerous friends, who met daily at the spring-fed community pool that was full of frogs, and kept a pen for his collection of pet box turtles. Free Acres was also an intellectual oasis for actors, writers, communists and anarchists, with James Cagney and Thorne Smith, who wrote Topper, regularly spending summers there. Jay also recalled Paul Robeson making several visits and performing at the community’s small outdoor theater.

My father graduated from Bayonne High School at the age of 14 and enrolled in New York University. Upon graduating summa cum laude from New York University when he was 18, Jay became the youngest person in the history of New Jersey to pass the state exam to become a Certified Public Accountant. He joined a Bayonne accounting firm and then met, and courted, Micki. Although he was six foot two and a brilliant college graduate, and Micki was a full foot shorter and had only a high school diploma, Jay was immediately attracted to her. She was spunky, vivacious, spontaneous, fun and gregarious, traits very unfamiliar yet enticing to Jay. They had dinners at Tavern on the Green, saw numerous Broadway plays and attended most of New York University’s basketball games at Madison Square Garden.

Mom and Dad got engaged in November 1948, married the following February and were totally in love. The fun and games, however, soon ended as, beginning in 1952, Micki gave birth to four children in six years. They bought a small house in Springfield, New Jersey, after number two was born and, shortly after the last child arrived in 1957, Jay decided to leave accounting. He and a partner bought a wholesale tobacco and candy business, which began a 10-year period where he worked six days a week, between 10 and 12 hours a day.

Mom, however, insisted we take a family vacation each year and Dad reluctantly agreed. That meant two weeks in Bass River on Cape Cod the end of every August. We weren’t exactly poor, but there was no money for any type of extravagance, so free entertainment was critical. That meant days at the beach, foraging for blue crabs along the banks of the Bass River or going out into the wilds and picking buckets of beech plums, which Mom converted into jelly when we returned home. That was fine for when the weather was good, but what to do when it rained? The solution was to visit antique shops. Mom and Dad felt guilty about always looking and never buying, so they decided they would have to start collecting something and, as luck would have it, they decided to collect cut glass knife rests.

Within a short time, a collection of 120 knife rests were assembled and proudly displayed in a special case in the living room. My parents soon became fascinated with all types and forms of brilliant cut glass and the collection expanded far beyond simple knife rests. They worked as a team, with Jay being the buyer and Micki memorizing and recognizing hundreds of different cut glass patterns. In all, they assembled over 600 objects of exceptional quality. Micki and Jay might have continued collecting American cut glass for the rest of their lives but their buying habits were radically altered and expanded by two influences.

The first was the Corning Museum of Glass. The museum began holding annual seminars in 1962, each one focusing on a particular aspect of glass making and glass history. Micki and Jay missed the first two because they did not know the seminars existed, but they attended their first one in 1964 and 52 more in the following 54 years. Jay’s enthusiasm for all types of glass was boundless and he spent hours doing research in the library. Micki helped with the research, but also brought boxes of home-made cookies for the librarians, who gladly went hunting through the stacks, fulfilling my dad’s near-unending requests.

My father’s thirst for knowledge was insatiable and soon became legendary. He loved talking about any and all facets of glassmaking and always arranged to have breakfasts and dinners with any and all craftsmen who were attending the seminar. He got into lengthy discussions with such artists as Dominick Labino, Harvey Littleton, Tom Patti, Paul Stankard and Marvin Lipofsky, while Mom kept the spouses entertained. It was also a common sight for Jay to be sitting at the bar of the Baron Steuben Hotel or the Radisson, with our pet beagle Cleo at his feet being fed goldfish crackers, buying drinks and striking up conversations with any glass artist, collector or scholar who walked by.

The other major influence in shaping my parents’ collecting habits was Minna Rosenblatt. Minna came to love antique glass while in her thirties and, with her husband Sid’s encouragement, started selling Art Nouveau glass from the basement of their Brooklyn home in the late 1950s. Minna was diagnosed with a form of leukemia in the mid-1960s and was told she had five years to live. Sid asked Minna what she wanted to do for the remainder of her life and her wish was to open a gallery on Madison Avenue. She did, survived the cancer, and lived for another 40 years doing what she loved best.

The Doros and Rosenblatt families soon became dear friends, but the beginning was a bit rocky. Jay and Micki would frequently drive into the city and spend hours in the gallery, talking about glass without buying anything. Sid constantly complained that Minna was wasting her time with those two dilettantes. However, my parents eventually became one of Minna’s best clients and always chuckled over her two favorite selling lines: “I’m charging you only $100 over cost” and “you’re making a mistake if you don’t buy this.”

For Dad, glass collecting was practically, if not actually, an addiction. They assembled representative groupings of Mt. Washington, Libbey Amberina, Durand, Quezal, Steuben and Tiffany Favrile. A serious problem soon developed, as the objects were quickly overtaking the limited living space in our small house. We all understood, however, that Jay’s enthusiastic buying habits could not be curtailed. So, one day late in 1975, Mom decided to have a heart-to-heart talk with Dad, and she asked me to come home to lend my support. She told him that he had to either focus on only one glassmaker or that we would have to move into a much bigger house. Dad loved the house, so he acquiesced and, thankfully, decided on Tiffany. All the cut glass, except for the knife rests, were sold at auction to help fund new Tiffany additions.

The first piece of blown Tiffany Favrile glass they bought was a pitcher (lot 230) with an ornate wheel cut and engraved design, which my parents felt was a suitable addition to the cut glass collection. The last piece they purchased was in 2017, accumulating over 500 objects in the intervening 45 years. Although the original, and primary, focus was on blown Favrile glass, Micki and Jay continuously researched and studied all aspects of Louis Tiffany and the Tiffany Studios. This resulted in expanding their expertise, and the collection, to include the company’s metalware, pottery, enamelware, mosaics and ephemera. Jay was especially proud that he was in the forefront of collecting Louis Tiffany’s paintings and the jewelry he designed for Tiffany & Company.

Once a piece was bought, its market value was never discussed again. Value at that point was totally irrelevant because it was never going to be sold. All that mattered was its significance to the collection as a whole. Mom and Dad never believed that their role was as keepers of the Louis Tiffany flame. The collection was for their own personal enjoyment and for the few people who were fortunate enough to be invited to visit the house and go on one of Jay’s lengthy but enjoyable “tours.” Dad would practically bounce from case to case, with a sparkle in his eye, talking enthusiastically, and sometimes endlessly, mostly about glassmaking techniques. And everyone was required to handle each and every object under discussion.

Many long-time and advanced art collectors frequently proclaim, when it comes time for the inevitable dispersal of their collections, that they are merely custodians or guardians for the next generation of collectors. That was definitely not my father’s attitude, as he considered every piece in the collection as one of his children. He let it be known many times, both privately and publicly, and only partially in jest, that his last wish would be to have a pyramid built in the backyard so that the entire collection could be entombed with him.

Thankfully, that proved to be impractical and my parents’ generous contributions of both objects and archival material to numerous institutions are a better indication of their ultimate goal, which was to advance and encourage the appreciation of art glass of all types. I, together with my sisters and brother, hope these series of auctions will help to serve and further that goal.