W e may all have been anticipating that, after months of Covid disruption in 2020, things would surely get back to normal in 2021... but no such luck. The pandemic continued to cause upheaval in global markets last year, and art was no exception. Travel restrictions had major consequences, such as the reshuffling of the fair calendar, the transformation of auctions and the continued refinement of galleries’ digital offerings.

The art market proved to be startlingly resilient, with auction houses staging some of their most lucrative sales ever. The Mei Moses All Art Index, which tracks re-sales of artworks at auction, registered a 17% increase in the value of art across categories – the highest year-on-year since the financial recovery in 2010. Meanwhile, average gallery closures did not materialise at the scale some feared.

Speaking to Sotheby’s magazine, experts look back on notable recent developments that will bear continued scrutiny in 2022.

Crypto wealth brings new buyers into the market

Art collectors’ wealth comes from diverse industries and with cryptocurrencies now more mainstream, Sotheby’s started to accept it as a form of payment in 2021.

“This is a major area of new client acquisition,” says Mari-Claudia Jiménez, chair, managing director and worldwide head of business development at Sotheby’s. “Justin Sun is the perfect example.” The tech billionaire bought Alberto Giacometti’s Le Nez (Nose) from the collection of real estate developer Harry Macklowe and his ex-wife Linda for $78.4 million at Sotheby’s last year. Sun also collects digital artist Pak as well as artists from KAWS to Picasso.

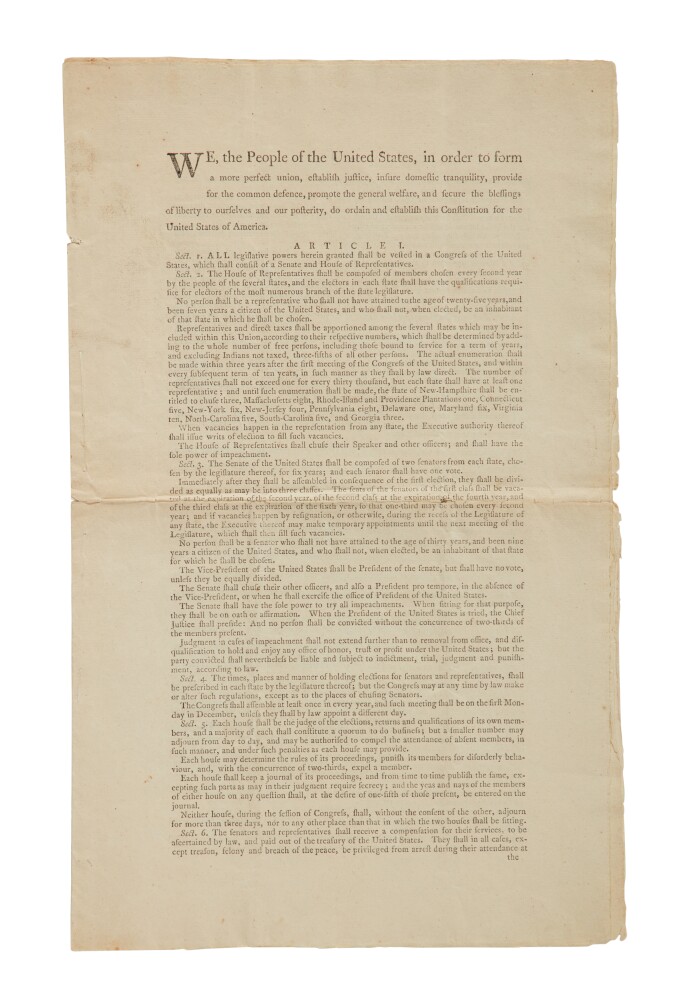

Crypto enthusiasts don’t always bid conventionally. In 2021 a 17,000-strong consortium, ConstitutionDAO (decentralised autonomous organisation), coordinated the largest crowdfunding campaign in history, raising $47 million to bid at Sotheby’s on a rare 1787 copy of the American constitution (estimate $15–20 million). The DAO publicly committed to bid up to $41 million, so hedge fund billionaire Ken Griffin knew how much it would take to beat them, and snatched it for $43.2 million.

If ConstitutionDAO’s bid was the beta version of DAO bidding, just days later (also at Sotheby’s), Abolition in Progress DAO won the declaration of the anti-slavery convention document, issued at the founding convention of the Anti-Slavery Society in 1833, paying $21,420 against a $5,000 high estimate.

The power of provenance

In uncertain times markets often see a “flight to quality” or proven assets. One indicator of worth is provenance, or history of ownership.

“People are drawn to stories,” says dealer and advisor Andrea Crane. “Provenance tells the story of where an object has been.”

Having been owned by beloved celebrities, respected artists or renowned museums can dramatically boost an artwork’s value, she says.

Collections from patrons who focused on exceptional works by canonical artists have lately proven irresistible. When 35 works from the Macklowe collection, including examples by Giacometti, Pollock, Rothko and Twombly, came to the block at Sotheby’s in November, it was a white glove sale that far exceeded its $400 million estimate. Totalling $676 million, it is the most valuable single-owner auction ever staged. The remainder of the collection will be sold in May.

At Christie’s in November, oil magnate Edwin Cox’s holdings of masters, including Caillebotte, Cézanne, and Van Gogh, demonstrated that even a category that is lately less fashionable than contemporary art could inspire deep bidding globally, exceeding its $268 million high estimate to total $332 million.

Jiménez says that some buyers need the stamp of approval of noted collectors. “It imparts a historical connection to the work and adds cachet,” she adds. “A good provenance is reassuring for collectors newer to the field, who want to jump into the deep end but are unsure of their choices.”

“The Now sale was devised in response to the sudden emergence of a huge class of collectors looking at the art of our time”

Why young artists are all the rage

There was also a rage for young artists in 2021: British painter Flora Yukhnovich nearly tripled her previous high at Sotheby’s in November, realising £2.25 million for I’ll Have What She’s Having, 2020; while in just one example of a sizzling market for young artists of the African diaspora, a painting less than a year old by Ghanaian-born Serge Attukwei Clottey, Fashion icons, 2020–21, fetched £340,200, more than eight times its high estimate, at Phillips.

At the November debut of Sotheby’s The Now Evening Auction, devoted solely to works produced in the past 20 years, one of many successes for young artists was María Berrío’s collage Flor, 2013, which commanded nearly eight times its high estimate. Lucius Elliott, head of the auction, explains that the sale “was devised in response to the sudden emergence of a huge class of collectors looking at the art of our time”.

Explaining the reason for breaking away these artists from existing post-war and contemporary sales, he says: “Seeing these artists together elevated them. Seeing a Matthew Wong next to a Laura Owens makes more sense than next to a Rothko.”

The buyers fit into different categories, he says, with some coming from a generation who also collect established artists, while others are interested solely in this material. “They’re also incredibly global,” Elliott adds. “There’s great depth from Europe and from Asia, a region which is typically a great driver. A number of buyers are very familiar names.”

Digital platforms broaden the art market

When galleries, fair halls and auction salesrooms went dark at the pandemic’s onset, art institutions previously slow to innovate digitally found themselves with no choice but to use online platforms to reach buyers.

This approach quickly accelerated. Galleries surveyed by economist Clare McAndrew for a mid- 2021 art market report published by UBS and Art Basel, for example, reported that more than a third of sales had taken place on dealers’ websites or through art fairs’ online viewing rooms.

One gallery that was ahead of the curve was Pace, which recently employed its first-ever online sales director, Christiana Ine-Kimba Boyle. She says that online visitorship has been broad. “It’s a unique combination of existing and newer clients, with the newer ones leaning toward under 40, but we do get older clients. I’ve been working with one collector who worked with Pace in the 1980s but had lost touch.”

The geographic reach is similarly wide, with visitors from locales ranging from Korea to Montana, Romania to Brazil.

The industry’s move online also occasioned increased transparency, through means such as Art Basel asking its dealers to indicate price ranges on the fair’s site. Pace’s website has a similar philosophy. “It’s been incredibly important to me to link the inventory status of artworks to our inventory system, so that at any given moment, if an artwork is reserved, it shows as such,” says Boyle. “This way, collectors know where they stand.”

NFTs shake up the art world

Until recently, few art worlders knew what NFTs were (much less the blockchain technology upon which non-fungible tokens depend). But since Beeple, aka Mike Winkelmann, became one of the highest-selling living artists when a digital collage of his sold for $69.3 million at Christie’s, NFTs have exploded into a major market.

Sotheby’s became the first auction house to open its own platform dedicated to NFTs, with the launch of the Sotheby’s Metaverse. In September, a group of 101 Bored Ape Yacht Club NFTs sold as a single lot for $24.4 million, more than doubling its estimate.

Bored Apes and Beeple aside, much of that market has remained outside of traditional art-world channels; in Art Basel/UBS’s mid-year 2021 report, dealers indicated that just 0.5 percent of their sales came from digital art sales.

While NFTs remain a small percentage of the market, auction houses and galleries have dived into the pool. Crypto-wealthy buyers may come for NFTs, says Jiménez, but they stay for the art. “NFTs are just one of the new categories that are gateway drugs, bringing in wealthy clients who never knew what Sotheby’s is,” she says. “They come for a Virgil Abloh sneaker, then they’re down the rabbit hole on other things they didn’t know they might be interested in.”

Cryptocurrency investor and digital art collector Pablo Rodriguez-Fraile collects artists such as Beeple and Pak in depth and displays his holdings in the RFC collection. He also co-founded NFT marketplace Aorist.

But while he’s deeply invested, he also sees the need for changes in the space, among them the decoupling of NFT art from cryptocurrencies. “We are at a point of explosion of interest, but the majority of the audience is thinking of NFTs as one big thing,” he says. “There are so many different asset classes within it,” he says, such as art, collectibles, music and gaming.

And while there’s nothing wrong with making money, he thinks it’s high time for more focus on art than profit. “The majority of the collectors come from the blockchain world, and are focused [more] on making money through these tokens than [on] the art itself,” he says.

But he’s confident that the technology behind NFTs will change the art world. “This is here to stay,” he says. “We need to mature as an industry, but there’s no doubt that tokenisation is the future.”

LEAD IMAGE: VINI NASO, KODAMA - SAMA, 2021, PART OF PABLO RODRIGUEZ-FRAILE'S DIGITAL ART COLLECTION. COURTESY: RFC COLLECTION