W hile the earliest known paintings in East Asia were painted on tomb walls, a variety of formats suited to portable viewing and storing of paintings and calligraphy have developed throughout China, Korea, and Japan over the past two millennia.

Traditionally, flat oval or round fans made of stiffened silk mounted on a bamboo stick were used in China, and gained popularity during the Song dynasty. Painted on sheets of paper or silk laid on a flat surface, the finished work was then mounted to a support using water soluble glue. The two surfaces could be separated and the mount replaced from time to time to help preserve the work.

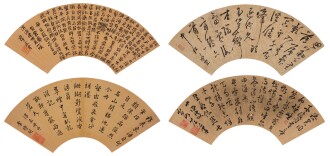

Due to their size, many fan leaf paintings were created as small gifts or commemorative pieces for special occasions, when something larger was not suitable. Some were dated and inscribed with comments from friends, or even executed by one or multiple artists.

Folding fans, made of folded paper mounted between thin bamboo sticks, are thought to have developed in Japan and Korea and then been exported to China during the Ming dynasty. The folding fan was almost the last pictorial format to be developed in China, and not widely used until the 16th and 17th centuries, which Craig Clunas, in his book Art in China, attributes to the “growing role of art in élite sociability at this time”.

Albums were also a common format for storing and displaying fan leaf paintings. To preserve the artwork and avoid sunlight exposure, fans were often removed from their bamboo frames and mounted onto individual pages (album leaves) which were then assembled in a book format of up to 12 folded pages and covered with wood or brocade-covered card. Some fan leaf paintings may never have been used as fans, but were instead mounted almost immediately into albums for the enjoyment of art collectors.

Viewed from right cover to left and organised according to a specific artist, period, or subject matter, leafing through an album provided a particularly intimate experience compared with viewing other formats of Chinese painting such as hanging scrolls or hand scrolls, which required the assistance of servants to handle the work. This direct engagement by a single viewer with the unfolding scenes within an album has been likened to a private experience of communing with the artist, in contrast with the more social occasion of viewing larger works.

“Long I lived checked by the bars of a cage; Now I have turned again to Nature and Freedom.”

Fan leaf paintings are most often associated with artists in the scholar tradition, and the format is said to have been a particular favourite of the Southern Song academy painters. The rise of literati paintings by scholar-painters prized personal, subjective expression over formal representation. Aiming to “satisfy the heart” first and foremost, they are commonly regarded as the peak of artistic achievement in Chinese art history.

For example, the Six Dynasties poet and politician Tao Yuanming is depicted by Chen Hongshou as he works on two fan paintings. Tao was exulted by influential Song literati such as Su Shi (1037–1101) for his decision to resign from civil service and live a simple, reclusive life. Accounts of his life usually praised his indifference to worldly concerns and emphasised the joys of creative authenticity and spontaneity.

Often decorated with landscapes, fan leaf paintings documented intimate glimpses of life – scholars reading under bamboo trees, travels through nature, flowers, animals, birds and insects – and were sometimes accompanied by calligraphic poems mounted on the other side of the fan or on the album’s facing page. Their small size required paintings and calligraphy to be executed with great skill and imagination. Hermitage by a pine-covered bluff, attributed to Yan Ciyu, is an example of how precise, delineated Northern Song rock and gnarled tree forms were contrasted with more suggestive, misty Southern song style to express an intimate and secluded side of nature. Such precious articles were often presented by the emperor to members of his court.

Even the modernists such as the painter and academic Fu Baoshi (傅抱石, 1904–1965) used fan paintings as a means of conveying their private inner worlds in the literati tradition. In contrast with his grand state-commissioned works, Fu’s fan paintings of travellers in the mountains or gazing reflectively at waterfalls were vehicles for self-expression that revealed acutely private emotions such as the struggles caused by his daughter’s illness, and are inscribed with dedications to his wife and eldest daughter.

Sotheby’s Hong Kong is delighted to present a selection of fan leaf paintings from the collection of Yee-Ming Kuo, the renowned Chinese diplomat and accomplished poet, which spans an impressive breadth of styles and schools of Chinese painting and calligraphy. The remarkable collection will be offered this spring at Fine Classical Chinese Paintings on 6 April 2023.