A mong the most significant painters of the twentieth century, Edward Hopper cultivated a quintessentially American aesthetic marked by evocative images that captured the subtle intrigue and psychological complexity of modern urban existence. His contemplation of the commonplace and his penetrating study of the psyche burrow deep beneath the unremarkable surfaces of archetypal American subjects: nighttime diners, dimly-lit hotel interiors, and forlorn vernacular architecture. Though based on a fundamental commitment to naturalistic representation, Hopper’s work transcends mere narrative illustration in search of the symbolic and suggestive.

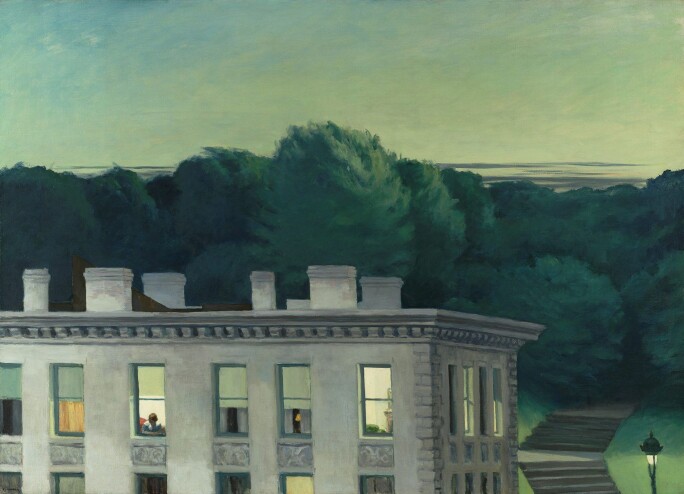

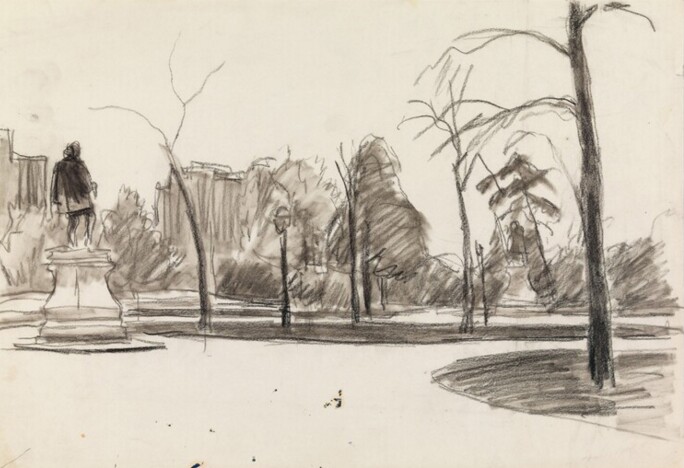

Painted in 1935, Shakespeare at Dusk captures the visual poetry of twilight in a large city, when the cacophonous noise of streetcars and elevated trains begins to acquiesce to the stillness of night. This Central Park scene belongs to Hopper's celebrated series of New York cityscapes – subject matter he explored early in his career while studying under Robert Henri and continued until his death in 1967. In this distinctly New York scene, Hopper depicts the southern end of the Central Park Mall illuminated by the vibrant afterglow of sunset. The inclusion of identifiable modern skyscrapers is exceedingly rare in his work and the present painting is one of only a few New York subjects where the exact physical location is clearly apparent. In the foreground, Hopper presents John Quincy Adams Ward’s full-standing sculptural portrait of the celebrated playwright William Shakespeare, with his head bowed in contemplative thought. While a universal representation of a city at twilight, Shakespeare at Dusk is an unmistakably New York image, whose Manhattan-specific subject matter is matched by its provenance, having once been in the collection of John J. Astor VI.

Shakespeare at Dusk is among the only major works by the artist that overtly references the profound influence of literature on his emotional response to specific times of day, particularly the evening. The poems that he quoted, often as explanations for his own art, frequently focus on the mood of dusk—its sense of mystery, anxiety, and eros born out of the varying effects of light and shadow.

The present work is singular in Hopper's œuvre in its direct reference to a literary figure that had a significant influence on the artist’s career. While most of his paintings contain elements of poetic inspiration, few are as forthright as Shakespeare at Dusk. As Gail Levin suggests, the title of the painting invites a comparison to the bard’s oft-quoted description of autumnal twilight:

That time of year thou mayst in me behold

When yellow leaves, or none, or few, do hang

Upon those boughs which shake against the cold,

Bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang.

In me thou see’st the twilight of such day

As after sunset fadeth in the west

Which by and by black night doth take away,

Death's second self, that seals up all in rest.

(William Shakespeare, Sonnet 73)

As Gail Levin proposes, the darker connotations of the last lines may have been particularly meaningful to Hopper whose mother had passed away earlier that year on March 20, 1935 at the age of eighty-one. The loss of his only surviving parent appears to have activated Hopper’s own conception of his mortality and his interest in evening’s waning light, as seen in Shakespeare at Dusk and House at Dusk (1935, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Virginia) of the same year (Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography, New York, 1995, updated & expanded 2007, p. 269).

New York’s connection to Shakespeare has a long and fascinating history. In 1864, coinciding with the tri-centennial of the English poet’s birth, a group of New York actors led by the noted thespian Edwin Booth received permission from Central Park’s Board of Commissioners to lay the foundation for a statue between two elms at the southern end of the Mall. Ward, called the ‘Dean of American Sculptors,’ won the commission and ultimately produced three other sculptures in Central Park. The park’s Shakespearean connections are many and varied: in 1890, the chairman of the American Acclimatization Society, Eugene Schieffelin, introduced the European starling into North America when he released 80 birds into Central Park purportedly because they were mentioned in Shakespeare’s “Henry IV, Part 1”—there are now over 200 million starlings in North America. In the present day, the Public Theater’s annual free performance of “Shakespeare in the Park” is one of New York’s most beloved summer traditions.

As with its relationship to the stage, Central Park has an equally important connection to music and film. Like Hopper’s poetic exploration of the city in Shakespeare at Dusk, several notable artists from the mid-twentieth century have also sought to capture the experience of an evening in Central Park. While modern painters and writers documented the impressions of New York’s burgeoning urban identity, musical studies into the city’s developing soundscapes were less forthcoming. Like Hopper, the American composer Charles Ives was caught between the nostalgia of the late nineteenth century and the sprawling industrialization of the early 1900s. In 1906, he created one of the first radical musical works of the twentieth century— “Central Park in the Dark.” In this experimental tonal poem, Ives explored the changing sounds of New York’s modern landscape.

One can imagine Hopper’s Shakespeare at Dusk as a visual companion to Ives’ symphonic “Central Park in the Dark.” Hopper, positioned on a bench near the Central Park Mall, would have certainly heard the nocturnal sounds that inspired the composer’s work. Ives’ music, like Hopper’s paintings, was grounded in an unvarnished realism that synthesized literary, philosophical, and pictorial narratives into an authentic artistic expression of a specific time and place.

Both Hopper's painting and Ives’ musical composition may have served as a basis for the famous nighttime Central Park scene in the moody and stylish B-movie thriller Cat People (1942), directed by Jacques Tourneur. In the well-known scene in Central Park, one of the main characters begins to believe that she’s being followed through the park by an unseen presence in the dark. Hopper’s art, which often directly referenced the cinema and film noir, has been a significant inspiration for generations of filmmakers including Alfred Hitchcock, Wim Wenders, David Lynch and Terrence Malick.

Hopper was also deeply influenced by the French photographer Eugène Atget, whose images of the Parc de Saint-Cloud share much in common with Hopper’s Central Park scene. The interdependent relationship that Shakespeare at Dusk has with different modes of artistic expression—music, film, photography, and the stage—demonstrates Hopper’s fruitful synthesis of various media, as well as his wide-ranging influence on writers, auteurs, and painters today.