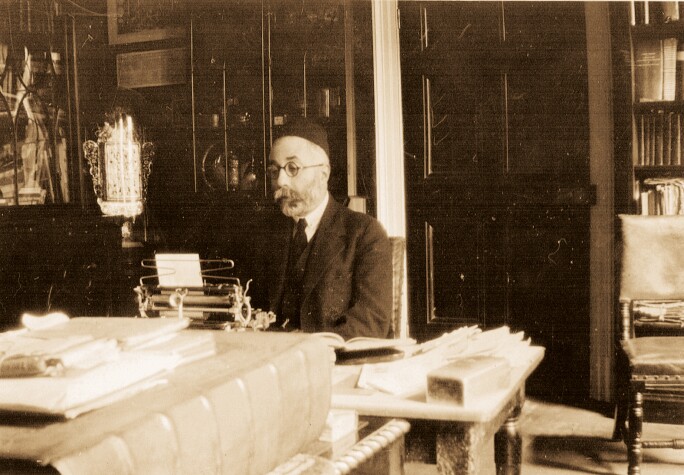

U ndoubtedly the most avid and prolific collector of Judaica of the Sassoon dynasty was David Solomon Sassoon. Born December 8, 1880 in Bombay, David was named for his paternal grandfather. Like his mother, David was educated in Jewish subjects, as well as Arabic reading and writing, by imported Baghdadi tutors, namely Rabbis Isaac Agassi and Joshua Abraham (1854-1915), the latter a descendant of the aforementioned Rabbi Sason Shindookh. By the age of eight, David writes in Divrei david, he knew the prayers for the entire liturgical year and practically the entire Hebrew Bible by heart. Also like his mother, he received his general education at a local non-Jewish (in this case, Anglican) institution, St. Peter’s High School.

David learned the family business from his mother in the period during which she headed the firm’s Bombay offices and served as chairwoman of the Sassoon Spinning and Weaving Co., Ltd., Sassoon and Alliance Silk Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Sassoon Pressing Co., Ltd., and the Port Canning and Land Improvement Co. Along the way, he also acquired a number of practical life skills, including shorthand, carpentry, horseback riding, and target practice. Together with the rest of his family, he moved to England in the early twentieth century and soon thereafter, on December 17, 1912, married Selina (Sarah Ziskha; 1883-1967) Prins, scion of two famous Ashkenazic families from Holland and Germany. The couple lived in the Sassoons’ stylish and spacious Mayfair home and had two children: Flora (Farha; 1914-2000) and Solomon (Sliman; 1915-1985).

David was humble and generous and cherished his parents, wife, and children, referring to them in devoted, loving, tender terms. He was also, in the words of a number of British judges in Calcutta (present-day Kolkata, India), “a very religious man.” From the age of bar mitzvah, he made sure to take shrouds and earth from the Holy Land with him on his journeys in case he would chance upon a Jew who died without anyone to give him or her a proper, traditional Jewish burial, as indeed happened when he was in Kobe, Japan, in 1897. Like his father, in 1902, he received a certificate authorizing him to slaughter fowl according to Jewish law. Also like his father, he maintained a synagogue in his London home. And together with his mother and wife, he supported numerous Jewish communal causes, both local and international: he served as treasurer of the Etz Chaim Yeshiva in London (1929), the English Pro-Falasha Committee, and a charity established to aid the Lubavitcher Rebbe during his hospitalization in Paris in 1937; member of the Commission for Kashruth in London; chairman of the Geonica Society (1931-1938); and elder of the Bevis Marks Synagogue (1938-1940). He also worked assiduously to save Jews fleeing Europe in advance of World War II, sometimes housing refugees in his own home.

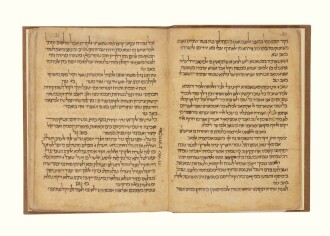

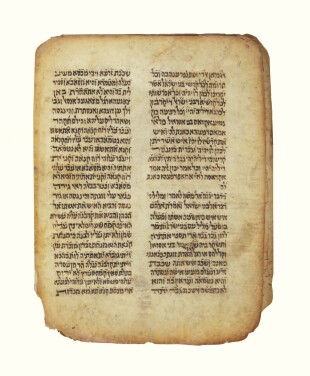

While he saw great success as a businessman, public activist, and philanthropist, David was at heart a scholar who felt most at home when he was in the study hall. He read widely in both traditional and modern academic literature, learned Farsi and Greek, and could even interpret hieroglyphics. Like his mother, he corresponded with and hosted some of the leading lights of contemporary Jewish society, from Hayyim Nahman Bialik and Nahum Sokolow to Samuel Krauss and Abraham Yaari to Rabbis Shemtob Gaguin, J.H. Hertz, and Isaac ha-Levi Herzog, among others. His first of many publications was a letter to the editor of Maggid meisharim (a Judeo-Arabic weekly that appeared in Calcutta), printed 26 Kislev 5650 (December 18, 1889), when he was barely nine years old. He would go on to author or edit six books and close to fifty articles, with others remaining to this day in manuscript. His magnum opus and most profound contribution to Jewish scholarship was the two-volume, 1,500-plus-page catalogue of the Hebrew and Samaritan manuscripts in his private possession, entitled Ohel Dawid and published in 1932 by Oxford University Press.

The seed for this library, hailed by Cecil Roth in 1941 as “one of the most magnificent collections of Hebrew manuscripts in private hands in the world to-day,” was planted early on. At the tender age of 8, David acquired his first booklet, an Arabic translation of Ruth printed in Bombay in 1859, by trading a friend a kite for it. From that point, virtually whenever he went abroad, David made sure to inquire about the availability for purchase of ancient, historically important, and/or beautifully illuminated Hebrew printed books and manuscripts. For instance, in 1902 he traveled to Damascus, where he bought the famous Rashba Bible, and the same year, during a trip to Egypt, he procured fragments from the Cairo Genizah. In March 1913, after an extended correspondence with the Farhi family in Aleppo, David finally managed to persuade them to sell him the eponymous Farhi Bible, one of the masterpieces of medieval Hebrew manuscript painting. His journeys through Europe, North Africa, and the Middle and Far East brought still more treasures into his growing collection. According to a 1975 Sotheby’s auction catalogue, David was “the chief buyer at the sales at Sotheby’s in London of the libraries of Solomon Schloss, Lord Amherst of Hackney (1908), Lord Vernon (1918), and others.” He also dealt extensively with prominent antiquarian booksellers like David Frankel, Lipa Schwager, and Jacob Moses Toledano.

As early as February 1914, Elkan Nathan Adler (1861-1946), perhaps the greatest Hebrew bibliophile of his age and a friend of David’s, characterized the 412 manuscripts then in the Sassoon collection as “of the highest importance, both from the artistic and literary point of view.” Over the following decades, David’s library would expand to comprise more than 1,270 Hebrew and Samaritan manuscripts and a wide range of printed volumes and lithographs, including over forty incunabula, twenty-eight books printed on parchment, and rare titles, periodicals, and broadsides published in Baghdad, Bombay, Poona, Calcutta, and the Far East. Unlike some collectors, who amassed rare books with no intention of studying them, Sassoon was intimately familiar with his library’s contents and used these texts for his own research and writing; furthermore, he selflessly made them available to other scholars, particularly following the publication of Ohel Dawid. The catalogue, probably the most learned inventory of a private Hebrew manuscript collection ever produced, is organized according to the following categories: Bible and Translations; Midrash, Bible Commentaries, and Homilies; Talmud and Halakhah; Liturgy; History; Philosophy and Theology; Kabbalah; Poetry; Philology; Medicine and Science; Miscellanies; Scrolls; and Samaritans, with a separate section devoted to recording inscriptions from buildings, cemeteries, and ritual objects, as well as extensive indexes. Sassoon, “the Elkan Adler of the Sephardim,” had hoped to catalogue or at least index his printed books and lithographs, too, but the project never materialized.

While David focused the bulk of his collecting efforts on books and manuscripts, he also inherited from his mother his uncle Reuben’s valuable silver Judaica, to which he added numerous antique ritual objects and textiles.

Following the Austrian Anschluss of March 1938, David saw the storm clouds of war gathering and decided to pack up a portion of his library. In his diary entry for April 11, 1938, David writes:

Last night, I removed some manuscripts and printed books from their home of many years—books with which I had passed my days and nights, books in which I delighted every day, holy books more precious and dear to me than much fine gold—and with great care wrapped them in paper in order to send them for safekeeping in a more secure place. This afternoon, my son Sliman, may God protect and keep him, and I took the packages and began to place them on the inner seat of a taxi. […] Later, my righteous duchess [Selina], may God protect and keep her, and I went to a place called Winchester House Safe Deposit, on [Old] Broad Street, and with a broken heart and crushed spirit, we stored the books in an ironclad room. I hugged and kissed them and pressed them against my eyes—the same eyes that saw by their light—and then took my leave of them, asking myself: when will they return to me?

Though he would eventually, on March 21, 1939, retrieve the volumes from Winchester House, his concerns for their safety were not unfounded, as the Sassoon residence was bombed one evening during the Blitz and almost all the windows were shattered; according to David, “nothing in the house remained whole.” Shortly thereafter, on October 7, 1940, the family relocated to 15 Sollershott East in Letchworth, about thirty-seven miles north of London, and it is here that David lived out his final two years, passing away on August 10, 1942. The library then came into the possession of Solomon David Sassoon, a rabbi and communal activist in his own right, who added modestly to the collection and published some of its manuscripts. He, his wife Alice (Aliza Beyla; d. 1998), and their family immigrated to Israel in 1970.

This year marks the fiftieth anniversary of Sassoon sales at Sotheby’s. In tribute to David Solomon Sassoon and his perennial quest to assemble, preserve, and share with others the best of the religious, cultural, and artistic heritage of the Jewish people, we end this catalogue as he did his, grateful for what we have accomplished even as we recognize that our work is not over:

Completed with the help of Heaven, blessed be He and blessed be His name forever—and may He lovingly aid us with what remains—on Monday, 15 Shevat, the new year for trees, in the year 5691 [February 2, 1931]. May this year bring an end to all our troubles and the beginning of good tidings for the magnificent nation. […] The author is the simple, humble David, son of my master, my father, the crown of my head, Sliman, son of David, son of Sassoon, may the memory of these righteous men be a blessing. May the Blessed God grant me the privilege to be counted among those who bring merit to the masses […] amen and amen.