In the lead up to S|2 London’s exhibition — Signals — from 27 April to 13 July, Sotheby’s interviewed one of the key artists exhibited at 1960s experimental gallery Signals London – Carlos Cruz-Diez. He is one of the originators of Kinetic and Op Art, a theorist of colour who sought to bring art away from the canvas and into space, to become a collaborative, co-operative creation. His involvement with Signals and its founders, along with a lifetime spent in the creation of energetic, visionary art, put him in an ideal position to tell us more about this exciting period in the history of art.

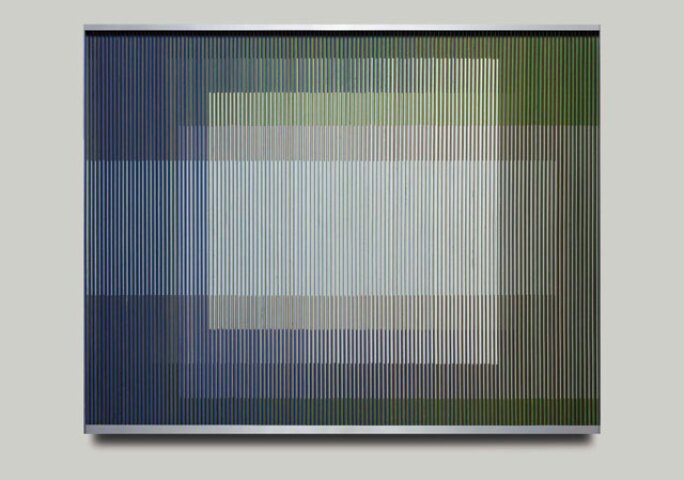

CARLOS CRUZ-DIEZ, FISICROMIA 3. © ADAGP, PARIS AND DACS, LONDON 2018.

26 February 2018 at the Artist’s Home in Paris. Originally conducted in English and Spanish and edited for publication

Bianca Chu and Francisco Arevalo: Maestro Cruz-Diez, we are so thrilled to be here to interview you in preparation for our Signals exhibition at S|2 Gallery in London. We wanted to ask you a couple of questions about your practice and a little bit about your experience in the sixties, and we are very interested to hear your insights from that time.

Carlos Cruz-Diez: It’s a pleasure. I came to Paris in 1960 from Venezuela. With me, I brought my [artistic] discourse and began to develop it there. It was an extremely creative time, many movements emerged between the sixties and seventies; many movements. At one point in 1964, Paul Keeler and David Medalla came to Paris from London. They came to visit our workshops and to see our works; they invited us to participate in group exhibitions and different exhibits that later he had travel through England.

BC/FA: Light, colour and movement seem to have always been central to your practice, what motivates you to explore these areas?

CCD: What motivated me to undertake a different adventure in painting was the result of a failure.

BC/FA: Can you explain a little more about that?

CCD: When I left the School of Fine Arts I thought that art was intimately linked to society and the painter should be like a reporter — paint what was in front of [one’s] eyes; and what was before my eyes was misery. I placed myself to paint the misery I was witnessing, thinking that with a painting I could modify a social condition; I failed.

At that point, I realised that colour had been maintained for millennia in art under the same concept. Colour was a material applied with a brush on a conventional support, when in fact colour is much more than that. Colour exists in space, colour does not need support, colour manifests itself permanently. It is a situation, an event that happens permanently in time and space. It is an eternal present; when it is painted on a support it is ‘past’.

BC/FA: And how does that link with your Physichromies in the fifties?

GUESTS AT THE PRIVATE VIEW OF CARLOS CRUZ-DIEZ, SIGNALS GALLERY, 1965 © CLAY PERRY, ENGLAND & CO, LONDON.

CCD: It is the way I discovered how to bring out colour by becoming and unravelling it before [one’s] eyes. I was able, at that point, to trap light in it of itself, in a way in which light and colour appears and disappears on a constant and continuous manner.

BC/FA: It is very poetic – the way [you] talk about colour… it almost feels as though it is alive. How important to you is audience participation and the reaction of people who see your artwork?

CCD: It has taken a long time for people to read the discourse well. At first, people did not see it and I remember when I made the first Chromosaturation in 1968, people entered the colour chambers and people would pass through because there were no paintings, there were no objects, there was nothing to see. What you had to see was space and people then couldn’t read or didn’t know how to see space.

BC/FA: Could we talk a little bit about your experiences in Europe in the fifties and the sixties? You began to live and work in Paris in 1960, what do you recall from this period in Europe?

CCD: It was a wonderful time of great creativity, and above all, of great camaraderie; the artists collaborated with each other to help each other become known. I [had] the advantage and the privilege of having begun to be known thanks to the artists who saw my work and invited me to exhibit in their galleries.

BC/FA: Part of the spirit of Signals is this collaborative nature, so we are very curious to hear more about these collaborations and this openness that you talk about experiencing in Paris.

CARLOS CRUZ-DIEZ, PHYSICROMIE NO. 54 © ADAGP, PARIS AND DACS, LONDON 2018.

CCD: I think Signals was a happy coincidence, the coincidence of three characters that were Paul Keeler, David Medalla and Guy Brett. Those three characters and others after, very close to the generation of the Beatles, created an immense euphoria focused on the renewal of language, Signals was the first gallery that took kinetic art to London.

BC/FA: Being part of a group of Latin American artists within Europe, did you feel that there was a sense of community for all of you living as part of a diaspora?

CCD: It was a historic coincidence. At that time many Latin American artists came to Paris and all [had] embarked on renewing the discourse because there was a feeling in Latin America: a desire for rupture that manifested itself [primarily] in the countries of Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, and Venezuela. These ruptures were the common element of their manifestos in Paris.

BC/FA: Can you speak a little bit more about Signals, about your first solo exhibition in the UK which was in 1965, focusing on the first decade of your Physichromies. What do you think of when you think of that exhibition or that time?

CCD: It was a happy coincidence, as I said, that Paul Keeler, David Medalla and Guy Brett were interested in the latest avant-garde movements. Kinetic Art is called the last vanguard as a collective movement, because after that there has been no other movement as collective as the kinetic and that allowed the development of new discourses, new supports of art, because art and painting had reached exhaustion.

BC/FA: Have your installations transformed as new technology is invented?

CCD: I have always been attentive to new technologies, to enrich my discourse; the important thing is to be efficient in what is said. If technology provides it, then I embrace them.

At the time of Signals, I went to London very often, almost every week we went to Signals because there was the opportunity to meet with friends, to talk, and above all, [to hear] what was being discussed at the time. It was an extremely rich time, very nourishing spiritually. I remember an exhibition, Paul Keeler toured the exhibitions in different cities of England and I remember one that Paul did in Eton (College). There are photos of me dressed up like an Etonian [in a tuxedo] ... (Laughs).

BC/FA: What did you think about them being all dressed up in tail coats?

CCD: It was very funny.

BC/FA: For us, [the spirit of] Signals is very much still alive and the people who were involved in it and who were touched by it are very much still present. The spirit of it is what we want to capture in this exhibition.

CCD: Our discourses and manifestos of all the kinetic artists are still valid, they have not aged.

BC/FA: No, exactly, they haven’t. They have just been, you know, maybe a little bit overlooked sometimes, but we want to bring it back to the forefront.

CCD: Historically, Kinetic Art is a movement that gives a renewal to art, renews support, renews behaviour; and it integrates time and space. Kinetic Art has contributed a lot to the history of art, what happened is that it was such a radical change that we had developed many enemies; we were attacked fiercely and it’s not until today that our contributions are finally understood. We transformed art from being a contemplative to a participatory experience.

CLICK HERE to view the full exhibition catalogue.