One of the most striking aspects of Il Volterrano’s talents is his versatility in all kinds of design. His drawings include studies for cupolas, escutcheons, pedestals, architectural mouldings, metalwork, tempietti, altarpieces, vases, cartouches and picture frames; the family of the Gherardesca, for whom he executed the fresco Truth illuminating human blindness, kept a volume of 400 of these drawings (fig. 1). They allow us to surmise how closely he must have been concerned in the design of the frames for his easel paintings – just as he created illusionistic borders for his frescoes.

The Gherardesca painting (1651–52) includes a double frame of a trompe l’œil cassetta in faux marbre with scrolling cartouches and foliate strapwork, within a garland frame of golden fruit. It was executed slightly earlier than the easel paintings produced for the Marchese Ridolfi (the present painting and figs 2 and 3) and suggests that the frames for the latter, of which the present painting possesses the sole complete example, were well within Volterrano’s design capabilities and almost certainly made from his own drawings.

In the early 1640s he had visited Bologna and probably Rome; in the early 1650s he repeated these trips, and the influence of both Bolognese and Roman Baroque fashion can be seen in the profiles and ornament of these frames. They are, or were, of a particularly unusual shape for portable frames, consisting of an oval torus moulding set within an octagonal contour (the latter retained on the present painting but excised at a later point in two of the frames; see figs 2 and 3); however, the frescoes which Volterrano completed for Lorenzo de’ Medici in the Villa La Petraia show that one of his compositional tricks was to nest different geometrical shapes within one another, setting octagons, ovals and tondi inside squares and rectangles.1

He also made frequent use of an oval format for paintings, many of his painted ceilings employing shaped picture planes within Baroque convex borders.2

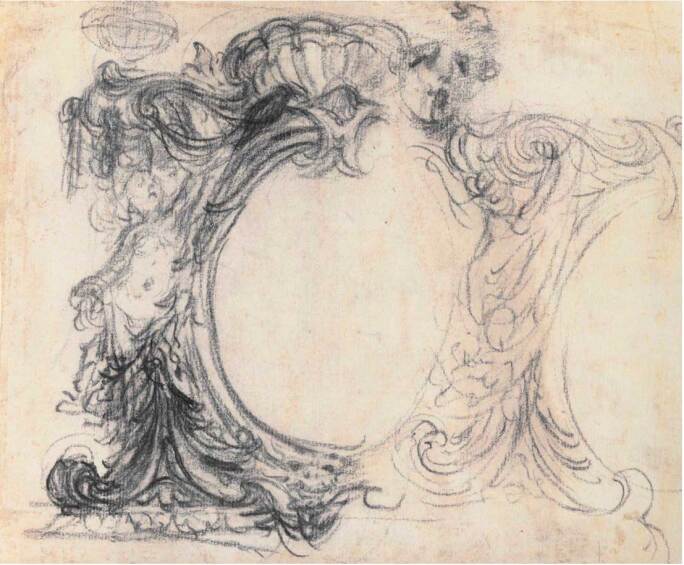

His drawings furnish a number of examples of frames and cartouches for oval paintings or inscriptions, and these – like the frescos in their painted borders – create a feeling of dramatic tension by opposing the clean curves of the sight edge with a much more dynamic outer contour (fig. 4). The ornament between the two may be made up of scrolling foliage, strapwork, clasps, shells, wings or putti, with exaggerated flutes adopted from earlier Mannerist borders; it is pulled into rough rectilinear and octagonal forms by the extension of the corners into swoops and volutes.

In the case of the current frame, the opulence of Volterrano’s designs has been tamed in a more sober interplay of geometry, possibly influenced by Roman models. The oval sight sits calmly in the outer octagon, and the sense of Baroque theatricality derives instead from the sculptural torus moulding at the top edge, the strong contrast of light and shade produced by the concave moulding behind it, and the grotesque masks with their topknots of leaves and flames which clasp the angles of the frame.

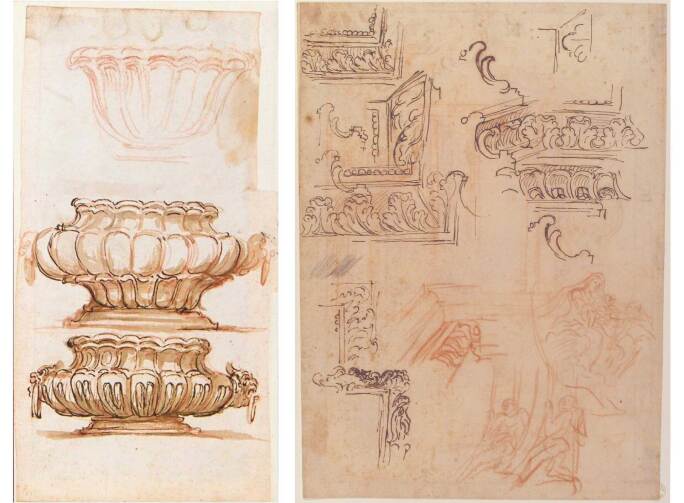

A characteristically Baroque ornament has been used to decorate the torus: a bold flute curved around it and – because of the oval format – appearing to radiate from the painted image, drawing the attention inexorably towards that image, and increasing the effect of perspectival recession within the picture-space. The finials of the masks emphasize and add to this optical effect. Similar flutes appear in Volterrano’s drawings for vases, basins and architectural mouldings (figs 5 and 6). The combination of this radiating ornament with the opposition of convex and concave mouldings is a trick designed to push the painted surface forward towards the spectator, isolating it from the richly coloured interiors of the 17th century and capturing the attention amidst competing decorative claims.

The masks are interesting (figs 7–9); they appear to take the form of three different animals in all the surviving frames – a bird-like being (probably intended to be a dolphin), a lion and a monkey. Volterrano uses grotesque masks both in his ornamental designs and in his paintings; they can be found, for example, in the frescoes of the Villa La Petraia, on a helmet and a fountain, where their presence seems to be purely decorative (fig. 10).

The masks on the frames, however, may have a symbolic as well as an ornamental aspect. They are stylized and deformed in the decorative style borrowed from the sixteenth-century Mannerism of Michelangelesque sculpture and its contemporary version seen in ‘Medici’ frames,3 but they can also be seen as representing various ideas and qualities. Thus, we have the dolphin which sometimes accompanies Cupid (the soul’s journey towards Platonic, ideal love); the lion, also shown with Cupid (‘Love conquers all’), symbolizing loyalty and courage; the monkey, which represents fraud and lust.

The theme of the group of paintings which Volterrano produced for Ridolfi, although at first sight disparate and unconnected, may also, under this reading, be linked in an allegorical procession of types of love. Perseus represents the bravery and self-sacrifice of love, which, like the lion, faces danger in its cause. The dying Cleopatra (now lost) stands for the fidelity of love, again like the lion. Fraud warns of false love, which betrays, like the lustful monkey, whilst Venus and Cupid may represent the two faces of love (eros and agape, or carnal and spiritual love). Orpheus and Eurydice, a very much larger rectilinear painting likewise commissioned by the Marchese Ridolfi and now in the collection of the Pucci family, may also have or have had a related frame binding it to the other works, amongst which it would stand for the journey of the soul towards divine love, and the survival of love beyond death.

The masks are surmounted on the top and inner side of the frame by two types of decorative motif (figs 11 and 12). One of them seems to depict a flaming torch, representing Eros or Love; the other is a sprig of leaves or petals – perhaps myrtle leaves, an attribute of Venus, or irises, attribute of the goddess Iris, companion of the souls of women on their journey to Elysium.4 The hollow moulding beneath the fluted top edge is decorated with bellflowers, known as ‘Venus’s looking-glass’, set between S-scrolls (fig. 13).

The number of motifs on these frames which bear some association with love in all its forms, taken with the subjects of the paintings, does give some justification for regarding Ridolfi’s commission as having a thematic coherence. Perhaps the room where the pictures hung in the Palazzo Ridolfi contained furniture which continued the theme – consoles, armchairs or looking-glass frames decorated with amorini.5

1 https://www.intoflorence.com/villa-della-petraia/

2 https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Cappella_orlandini-concini,_volta_del_volterrano_03.JPG

4 This would fit with Maria Cecilia Fabbri’s thesis that the Orpheus and Eurydice was commissioned by Ridolfi after the death of his brother’s wife; see Fabbri, Grassi and Spinelli 2013, pp. 216–17.