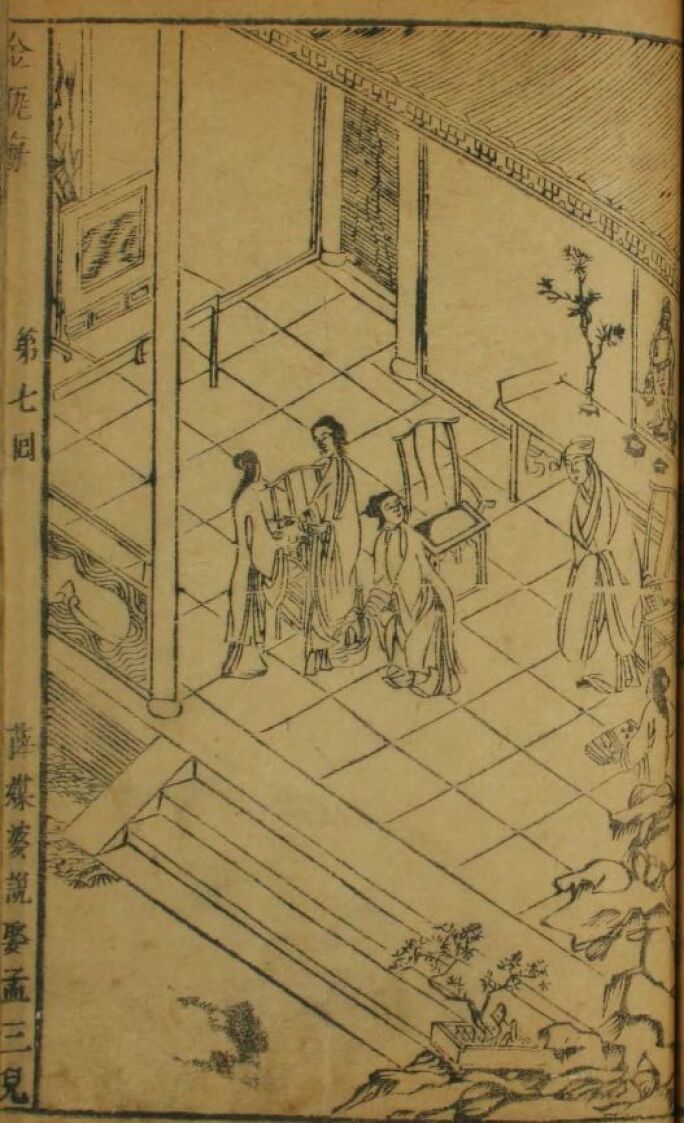

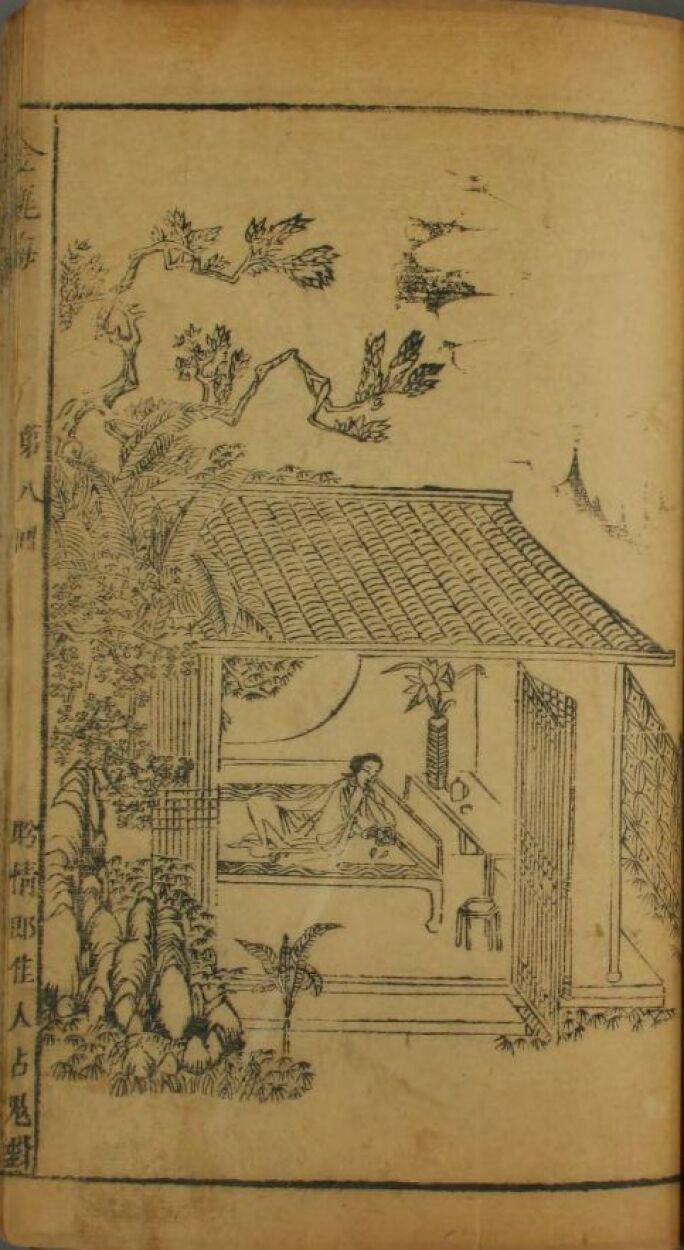

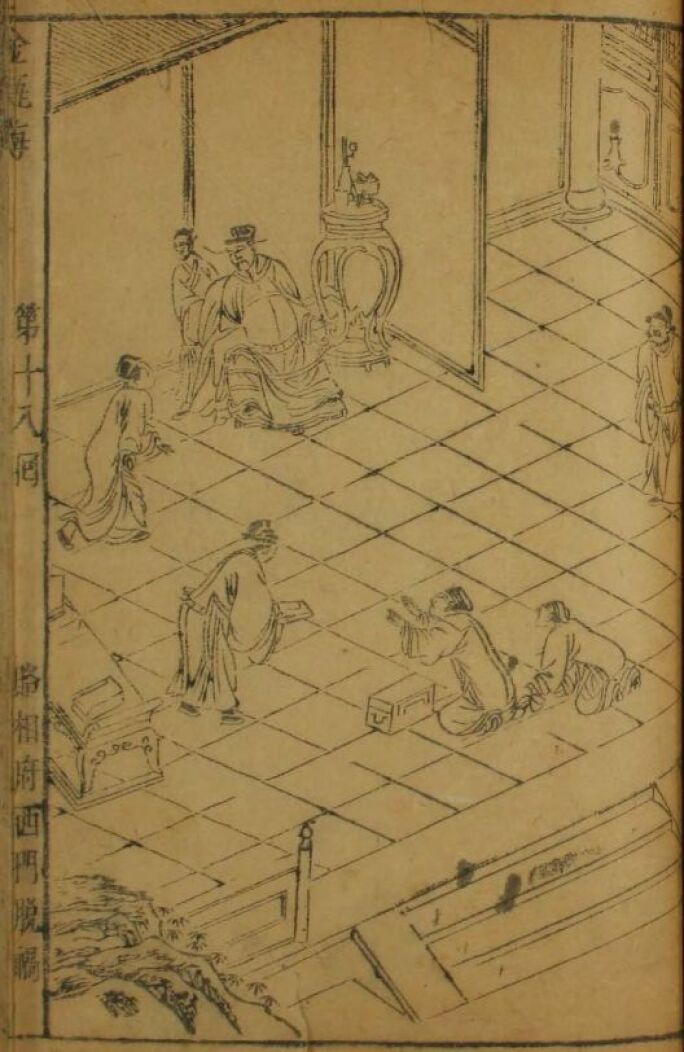

Ming dynasty Chinese furniture, when viewed in context of their original surroundings, can offer insights into life from a past era and the people who inhabited these interiors.

T oward the end of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), many literati scholars resigned their official positions, seeing their good work gone to waste in a realm plagued by corruption. Instead, they returned to private life and refocused their efforts toward fostering their own artistic creativity and appreciation for aesthetics – sometimes focusing on their surroundings at home. This shift would have an influence on styles of Ming dynasty furniture. The scholars would express certain preferences to craftsmen who would in turn design pieces of furniture that were suitable both in aesthetics and intellectual temperament. Often, they would favor huanghuali wood, a rare natural material that perfectly complement a minimalist sensibility.

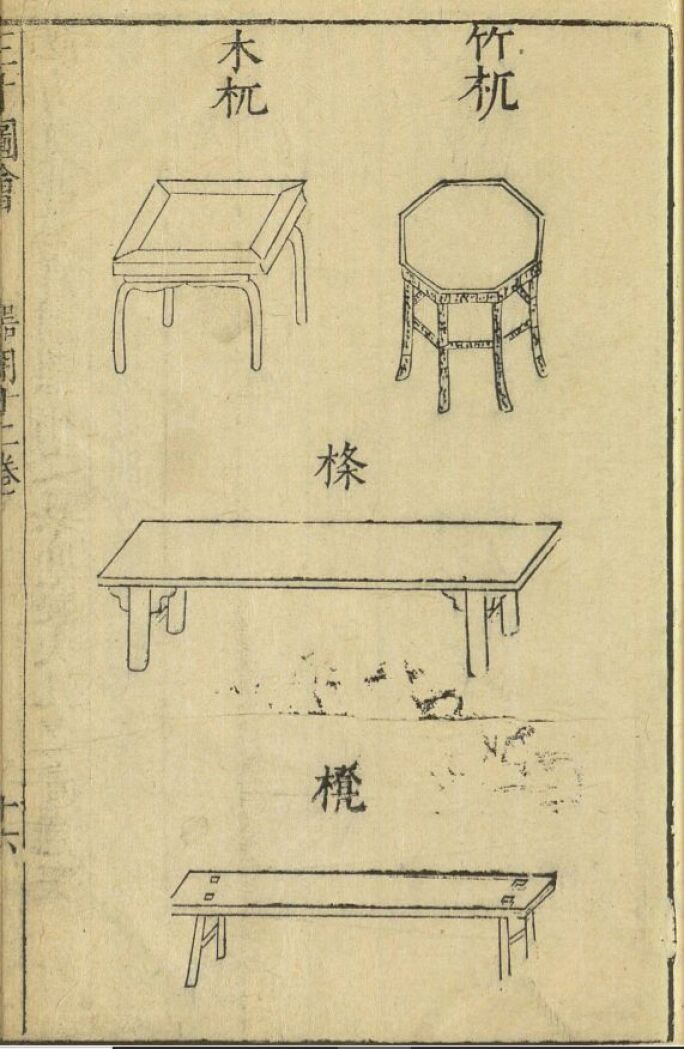

This coincided with a period that might be considered the golden age of Chinese woodblock illustrations. Renowned literati scholars in this movement included Qiu Ying, Tang Yin and Guo Zhengyi and Chen Honghuan. A diverse range of illustrations were created based on classics from traditional Chinese theatre, opera and literature, or from scholarly compendia or other references. These illustrations were often aspirational and provided a fascinating glimpse into daily life – a setting that revealed a diverse, range of different styles. For those who appreciate Ming dynasty furniture, it is a treat to see the pieces as they might have appeared in context of their original time, depicted within these realistically rendered illustrations. These images offer important and invaluable visual references for the study of Ming style furniture.

Rare Folding Stool

A Rare Huanghuali Folding Stool, Jiaowu

17th Century

Estimate: HK$400,000 — 600,000

Lightweight and comfortable, jiaowu or mazha, is a particularly convenient seating option for travellers and appears to be the first elevated type of seat in China. This design derives from prototypes known since the Han dynasty, when folding stools were imported by nomadic tribes from Central Asia. Emperor Ling (168-189) of the Eastern Han dynasty was fascinated by foreign fashion, including the exotic portable seat. He popularized its use in China as the nobility in the capital rushed to follow Emperor Ling’s example.

A Large Yoke-Back Armchair

AN EXTREMELY RARE AND LARGE HUANGHUALI YOKE-BACK ARMCHAIR, CHANYI

LATE MING DYNASTY

Estimate: HK$1,000,000 — 2,000,000

This yoke-back armchair is particularly notable for its large size and appears to be among the tallest chairs of its type recorded. The seat of the chair is spacious enough for sitting cross-legged, and the chair was likely to have been used for meditation. Despite its large proportions, a sense of lightness is captured through the gentle curves of the top rail and the S-curve of the tall back splat. The encourages an upright posture, thus endowed the sitter with an air of authority and prestige.

Qiaotouan Long Table

A RARE HUANGHUALI RECESSED-LEG LONG TABLE, QIAOTOUAN

MING DYNASTY, 17TH CENTURY

Estimate: HK$4,000,000 — 6,000,000

This piece is an exceptional example of a qiaotouan altar table with the top fashioned from a single huanghuali plank of unusually large size. It is also striking for its precise and lively carving that reveal a master workshop, from the vivid phoenix spandrels with their bodies swirling upwards, to the confronting chilong that decorate the panels between the legs, and the fine beading on the legs which make the table appear taller.

The qiaotouan is versatile, and may be placed in the hall for the display of antiques or in the studio as a painting table. In a grand hall, this table would have had a commanding presence, leaving no doubt as to wealth and social standing of its owner.

A Pair of Quanyi Circular Chairs

A PAIR OF HUANGHUALI CONTINUOUS HORSESHOE-BACK ARMCHAIRS, QUANYI

LATE MING DYNASTY

Estimate: HK$1,000,000 — 2,000,000

Known as quanyi circular chair, these horseshoe-back chairs derive from chairs made of pliable lengths of bamboo, bent into a “U”-shape and bound together using natural fibres. These chairs display the ingenuity of Ming dynasty cabinet makers, who were able to create a hardwood version by developing complicated joinery techniques.

Elegantly constructed with a wide back splat and precisely carved with confronting chilong enclosed in a ruyi-shaped medallion, these chairs owe their aesthetic appeal to the fluid movement created by their continuous crest rail, which provides a sense of containment and ease to their occupants. Comfortable, sturdy and lightweight, horseshoe-back chairs were highly popular in the Ming and Qing dynasties, and were frequently depicted in contemporary woodblock illustrated books. In ancient China, quanyi was used for either the master of the house or important guests who were close to the family.

A Recessed-Leg Bench

A HUANGHUALI RECESSED-LEG BENCH, CHUNDENG

17TH CENTURY

Estimate: HK$1,200,000 — 1,800,000

This bench is notable for its large dimensions and sturdy appearance, achieved through the square-section legs which gently splay outwards. Its gentle, elegant lines and nimble curves reflect influences from the Song dynasty.

Benches were very popular in the Ming and Qing dynasties as they were highly functional: their light weight and soft-cane seats, which permitted air circulation, made them ideal to be used both indoors and outdoors during warm summer days, while their large size and sturdy construction allowed them to function also as daybeds or for the display of small treasured objects.

A 'Kui Dragon' Couch-Bed

A RARE HUANGHUALI 'KUI DRAGON' COUCH-BED, LUOHANCHUANG

MING DYNASTY, 17TH CENTURY

Estimate: HK$3,000,000 — 5,000,000

This attractive luohanchuang couch-bed represents one of the most elegant and recognizable forms of Chinese classical furniture. Its powerful incurved feet and convex apron impart a sense of stability and strength, while the three solid panels with subtly sloping ends would have framed the sitter to provide both an intimate space and a platform that imparts prestige. Drawing from Chinese traditional iconography, the intricately carved kui dragons grant a sense of opulence and make this piece particularly rare.

The versatility of the luohanchuang meant they enjoyed great popularity in the Ming and Qing dynasty. Used as a couch during the day and a bed at night, couch beds were found in scholar’s studios and garden pavilions, at reception halls and in women’s quarters. Wen Zhenheng (1585-1645) “Chang wu zhi” (“Treaties on superfluous things”), he writes “There was no way they [couches] were not convenient, whether for sitting up, lying down or reclining. In moments of pleasant relaxation, they would spread out classic or historical texts, examine works of calligraphy or painting, display ancient bronze vessels, dine or take a nap, as the furniture was suitable for all these things.”

An Ebony-Inset Painting Table

A RARE HUANGHUALI EBONY-INSET PAINTING TABLE, HUAZHUO

QING DYNASTY, 18TH CENTURY

Estimate: HK$1,500,000 — 2,500,000

The ingenious design and the superior quality of this table suggests an imperial connection. It is striking for its clean and sober lines which are enlivened by the ebony lattice apron, whose lustrous dark tone also creates an attractive contrast to the honey-toned huanghuali. In its combination of the deceptively simple simianping or four-sided-flushed construction and sophisticated latticework, this table exemplifies the Qing carpenters’ efforts to create furniture that echoed and enhanced elements of traditional Chinese architecture. The result is a table that is both functional and decorative, and one that celebrates the natural beauty of the two woods.

Five-Legged Circular Incense Stand

A HUANGHUALI FIVE-LEGGED CIRCULAR INCENSE STAND, XIANGJI

17TH CENTURY

Estimate: HK$800,000 — 1,200,000

Striking for its elegant slender form and sense of movement in its subtly rounded curves, stands of this type with five cabriole legs are generally known as incense stands, which clearly define their first and foremost purpose, although they were at times used for displaying curious rocks, flower vases or candle sticks. The design first became popular in the Yuan period (1279-1368), and was gradually perfected in the Ming dynasty. Early examples of the type were beautifully designed and well-constructed with slender incurved legs that frame sensuous arched openings of various shapes.