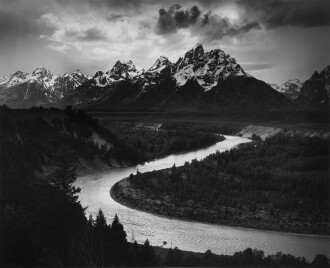

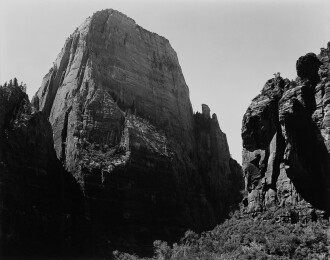

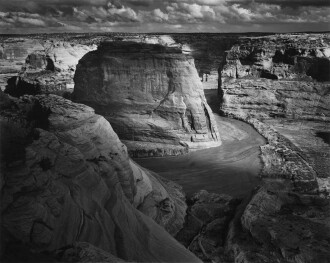

T he auction A Grand Vision: The David H. Arrington Collection of Ansel Adams Masterworks presents one hundred of Ansel Adams’s best and rarest photographs assiduously gathered over more than a quarter century. Within this sale, the master photographer’s images taken in North America’s national parks are extraordinarily wide-ranging in terms of geography, time period, and print size. Featured parks and monuments include Glacier National Park in Montana, Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park (lot 6 and lot 48), Utah’s Zion National Park, Mount Rainier National Park in Washington, as well as Canyon De Chelly National Monument (lot 22 and lot 91) and the Grand Canyon National Park, both in Arizona.

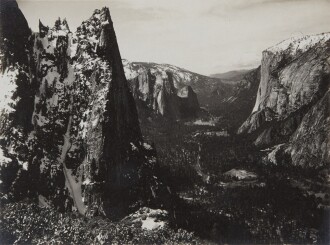

In early 1916, the fourteen-year-old Adams encountered Yosemite National Park for the first time through the pages of J.M. Hutchings’s 1886 book In the Heart of the Sierras. The volume was packed with maps, illustrations, and photographs of the majestic landscape, which had been placed under the protection of the State of California in 1864 and then designated a national park in 1890. Adams’s first trip to Yosemite occurred in June 1916, at which time his parents gave him his first camera — a Kodak No. 1 Brownie — to document their vacation. It marked the first of his many excursions to Yosemite to photograph everything from the valley floor to the dizzying views from Inspiration Point.

Each subsequent summer for the rest of his life, Adams returned to Yosemite to explore and photograph its myriad nooks and crannies. Beginning in 1920, he served for four years as the summer custodian of LeConte Memorial Lodge, a modest stone structure maintained by the Sierra Club. A horizontal image of the building became Adams’s first published photograph when it appeared in the San Francisco magazine Overland Monthly in 1921. The earliest print included in this auction dates to 1920, the year of Adams’s first summer at LeConte; Lost Valley, Yosemite may be small in physical size, but it is immense in scope.

Adams’s deep-seated love of Yosemite expanded into his life-long advocacy of the National Park System, the concept for which developed out of the U.S. Geological Survey teams who photographed unpopulated swaths of the North American landscape in the 1860s and 1870s. While the Survey initially aimed to earmark locations with valuable natural resources that could support future industry, the photographs they produced captivated both politicians and citizens, who were awestruck by the beauty of the Western landscape captured by Carleton Watkins, William Henry Jackson, and others.

Today’s modern conservation movement was largely born out of these daring, often death-defying photographs made deep in the mountains and valleys of America. Watkins’s photographs throughout the Sierra Nevada helped to establish a park in the Yosemite Valley in 1864 when President Abraham Lincoln signed the Yosemite Grant, thereby placing this wilderness area in the care of the State of California. In 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Congressional bill that designated Yellowstone the first national park — a decision influenced in no small measure by Jackson’s photographs of this area.

“I believe the approach of the artist and the approach of the environmentalist are fairly close in that both are, to a rather impressive degree, concerned with the ‘affirmation of life.’ … Response to natural beauty is one of the foundations of the environmental movement.”

By the time Adams took his first hike in Yosemite in 1916, the United States boasted thirty-five national parks and monuments. As a budding outdoorsman, he joined the Sierra Club in 1919. Adams had a life-long relationship with the Club, which was founded by the naturalist John Muir and supporters in 1892 as a vehicle to support land conservation in California. He not only photographed its annual outings, but eventually served on its Board of Directors for thirty-seven years.

Adams’s most encyclopedic body of photographs from the 1920s documents his numerous outings in the Sierra Nevada. In 1927 he released his first portfolio, Parmelian Prints of the High Sierras, comprising eighteen photographs taken in the 1920s. Extant complete Parmelian Prints portfolios are rare; although published in a projected edition of one hundred and fifty, only seventy-five are believed to have been completed, many of which are now in institutional collections or have been disassembled. This portfolio — originally marketed for $50 — represents Adams’s first major commercial endeavor and a crucial turning point in his development as a professional photographer.

His work with the Sierra Club directly led to Adams’s engagement with land conservation on a national level. Shortly after joining the Club’s Board of Trustees in 1934, he traveled to Washington, D.C., on its behalf to advocate for the demarcation of Kings Canyon as a national park. He brought a portfolio of photographs to persuade public officials and make his case for protecting this special area located to the south of Yosemite. Those images evolved into his 1938 limited edition publication, Sierra Nevada: The John Muir Trail — an early example of Adams’s understanding of how to use photographs for publicity and marketing. He sent copies to elected officials as well as the Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, who shared it with President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Largely because of Adams’s efforts on behalf of the Sierra Club, Kings Canyon National Park was established by Congress in 1940. Adams later recounted in The Eloquent Light that Arno Cammerer, director of the National Park Service, wrote to him: “I realize that a silent but most effective weapon in the campaign was your own book. … So long as that book is in existence, it will go on justifying the park.”

“As the fisherman depends upon the rivers, lakes and seas, and the farmer upon the land for his existence, so does mankind in general depend upon the beauty of the world about him for his spiritual and emotional existence.”

The next year, Secretary Ickes commissioned Adams to devise a series of murals for the Department of the Interior that would celebrate the National Park System. Delving into the project, Adam made more than two hundred exposures at national parks across the country over the course of many months. The mural project was disrupted by the United States’ entrance into World War II, but Adams’s widespread documentation of national parks further strengthened his conservation efforts.

Adams emphasized in his autobiography that he “never intentionally made a creative photograph that related directly to an environmental issue.” Rather, his intention for making a photograph was rooted in his desire to capture the intense beauty of the wilderness as well as the emotional or spiritual reaction one could experience by observing nature. His conservation efforts were a by-product of his fascination with and respect for the natural world.

In 1955, he and Nancy Newhall, his friend and a noted photography historian, curated the exhibition This Is the American Earth, which told the history of Yosemite National Park through Adams’s images taken over three decades. The Sierra Club published a book by the same name in 1960, which stands as a permanent record of the exhibition.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Adams met with numerous U.S. presidents to advance environmental causes. In late 1980, shortly after Adams had sent President Jimmy Carter a print of his 1948 image Mount McKinley and Wonder Lake, Denali National Park, Alaska, Carter signed the largest land preservation act in history, which converted more than forty-five million acres in Alaska into national parks and preserves. In the same year, Carter bestowed Adams with the National Medal of Freedom for his sustained efforts to conserve and protect the American wilderness.

In addition to the widespread admiration of his photographs, perhaps the most poignant acknowledgment of Adams’s conservation efforts occurred after his death in 1984, when an area in the Sierra Nevada was named after Adams in tribute to his herculean preservation work over the course of his lifetime.