AG Rosen was aware, when growing up in New Jersey, that some of what his father Saul did was collect art. So it’s not surprising that young AG, while still a college kid studying art history at Columbia, acquired a few things himself. When Kenny Goldsmith, an artist he knew and collected, brought him and Debi Sonzogni into my small, third-floor gallery in Great Barrington, MA, in September of 1992, we couldn’t have guessed that it was a meeting that would change all of our lives in fresh ways.

I had just shown two gorgeous Kenny drawings in my second exhibition, a group show in August. As new friends often do, Kenny and I were exchanging enthusiasms. I was giving Kenny books of poetry, and Kenny was putting me in touch with artists and collectors he knew and liked.

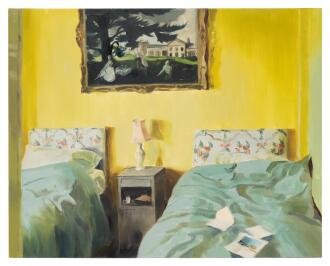

From that day forward AG and I began to work together, intermittently, but steadily. What was amazing and fortuitous, our tastes lined up extraordinarily well. For example, he was interested in Jacqueline Humphries’ paintings, and as it turned out, I’d just published an article about her, in Arts Magazine.

We’d enter a gallery or studio, and know right away whether or not we had business there.

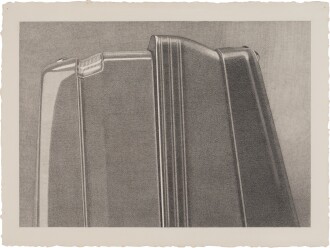

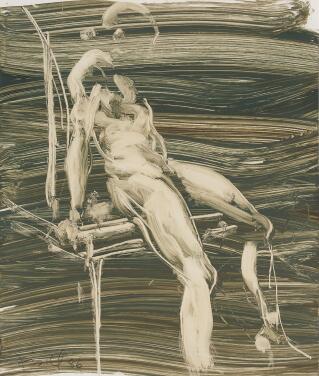

And AG was as sensitive to works on paper as he was to paintings and photographs. Drawing always engaged him. He liked fine, closely-valued work, as did I—what Jerry Saltz rather derisively dubbed “termite art,” as well as broadly gestural work, often outrageous in narrative content. The active imagination of the artist appealed to AG, as did the hand that delivered that vision. Open to a wide range of imagery, AG’s hunger for the new focused his attention. He trusted his feelings. And bought what he could of the best of what he saw.

His collection had been growing steadily, prior to our meeting, guided in part by several consultant/dealers. So, working with me, as with them, was more the norm, than an aberration. We’d meet up in SOHO in the 90s, and after visiting 10-15 galleries, or several studio visits, ask ourselves, “What did we see today?”

If we found things worth pursuing, we’d talk about it at suppertime over a glass of wine at Blue Ribbon, or any one of a number of local restaurants.

We’d return in memory to the shows we’d seen. Did anything we see stimulate our praise, generate an active desire to pursue the work? Did we know the artist? The gallery owner? The gallery director? Collecting is fueled by love. AG never once worried about, nor thought out loud, as to whether or not a work would gain in value. What mattered was how he felt about it now, and did he want to buy it?

Always decisive, we’d put reserves on work he wanted and puzzle out the prices later. It was good to stick with artists we liked, and see them grow over a decade or more, supporting them by buying work when we could, but at the same time, we were constantly in touch with new artists and new works. And I, with a gallery of my own, open in summer and fall, felt his commitment to my group shows as well. He and Debi would arrive mid afternoon on the day of the opening, and more often than not, acquire several works. Support like that mattered. It’s good to remember that the dealer is only as good as the money he gets the artists. With AG’s quick eye for the new, the artists benefitted and the gallery got stronger.

Here’s a brief account of the acquisition of three works, as examples of the excitement that collecting can generate. We’d seen one of Vija Celmins’ “meteor” drawings at David McKee Gallery, and loved it. It wasn’t available—not being offered-- but we let Renee McKee know how much we liked it. A couple of weeks go by and I get a call from Renee, saying, the Celmins drawing is now available, and would we like to come by and see it again? We were there the next day! One of her classic night skies, with deep space and stars, AND a meteor flashing by, from left to right: “Yes,” AG said.

Another story: we’re in Los Angeles, and we go to the Marc Selwyn Gallery in Beverly Hills. Unassuming, on one wall, is a beautiful, delicate gridded watercolor, in light orange, on crinkly paper, by Agnes Martin. Not large, but humming with mysterious presence, like sleight of hand. A rarity, on the market. AG was only too happy to buy it.

And one day, going from gallery to gallery on 57th St., we stopped at the Joan Washburn Gallery. On the wall, and for sale, was an important Myron Stout work on paper. “Tereisias 1,” from 1964. Yes, it might have seemed expensive, but who was counting? A brilliant gem, the real thing, something truly special. We hadn’t known about it. We were just going up one set of stairs after another, keeping our eyes peeled. Then this marvelous Stout falls in his lap. That’s the excitement a collector feels. By hitting the streets (taking his chances)--and by pushing buttons in slow elevators--a collector gets a shot at more than he knew existed.

Appetite and serendipity. Sometimes, if you’re lucky, they go hand in glove.

Over the years collecting has cemented many friendships over shared meals and information, and--the sine qua non—brightened our lives in the presence of untold quantities of art, as well as time spent among the lovable quirks and exquisite genius of artists. Trips to Los Angeles and San Francisco, as well as to Boston, to see the work of friends, or Museum shows, or to visit the studios of artists we were keen on, would break up the long winters. As the collection grew, artists new on the scene would be added to the major, minor and as-yet completely unknown artists already in the collection. With no goal to reach (the collection was open ended, with no aesthetic constraints hampering desire), the only motivating force was the pleasure of the hunt and the love of art.

Naturally, along the way there were loans to museums. AG and Debi were inclined to share the treasures. And sometimes, when possible, to give work away. For example, Deborah Kass’s An American Man, 1997, was given to the Jewish Museum. Appropriating the iconography of Warhol’s The American Man, Kass replaced Watson Powell’s face with AG Rosen’s.

And similarly, that’s how MOMA in New York acquired a suite of large James Siena drawings. Made in 1996, MOMA was happy to receive them as a gift twenty years later. Naturally, Siena and AG were thrilled as well. Great art belongs in the public trust, whenever possible.

Because nothing lasts forever, the collection is now moving into the next phase.

A substantial number of terrific works will be finding themselves in new homes. It was love that brought them together over a period of 40 years, and it is love that keeps them moving now, into the future.

![View 1 of Lot 71: Q [A Double-Sided Work]](https://sothebys-com.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/60c9786/2147483647/strip/true/crop/5605x4849+0+0/resize/330x285!/quality/90/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fsothebys-md.brightspotcdn.com%2Ff2%2F00%2F9d153f7b49da95bcfaea61b7727b%2Fn11290-cqp99-t2-02-a.jpg)