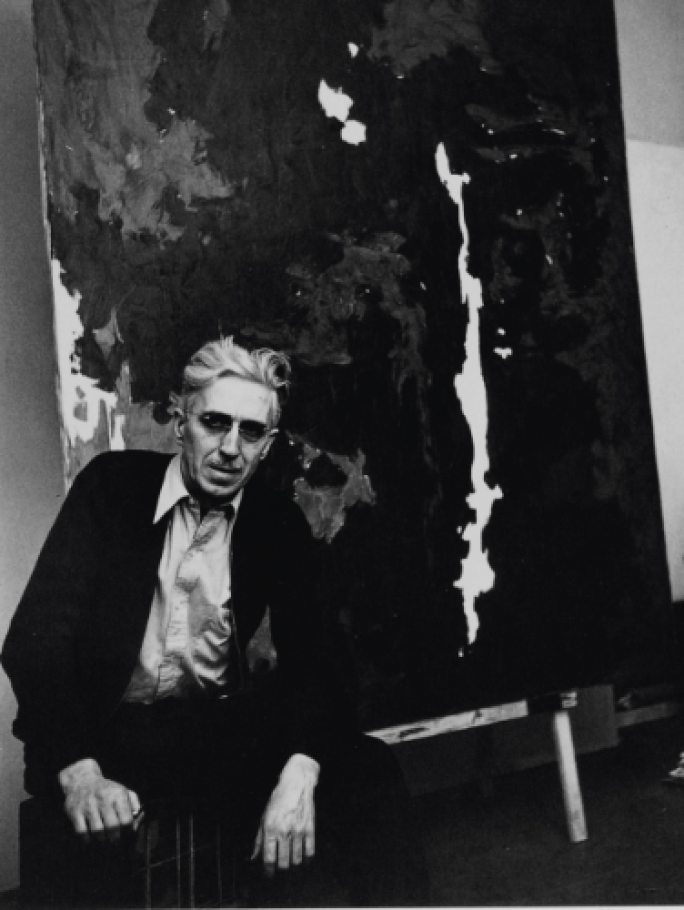

Personally gifted by Clyfford Still to his daughter, Sandra Still, PH-306 from 1946-1947 is an intense work from the artist’s seminal period in the 1940s. The exemplary painting will feature in Sotheby’s Hong Kong’s Contemporary Art Evening Auction on 9 July. Here, art historian David Anfam explores the signal importance of PH-306.

F undamental to Clyfford Still’s vision was an early encounter with nature. Shortly after his birth in North Dakota in 1904 Still’s family had moved to Spokane in Washington State and, from 1911 onwards, they farmed the prairies of southern Alberta, Canada. There, Still experienced harsh conditions that prompted a love-hate relationship to the environment. In particular, the landscape’s vast horizontality, which he called its “awful bigness”, instilled a polarization in his imagery. On the one hand, large expanses of land and sky expressed the force – at once vibrant and threatening – of sheer space itself. On the other hand, verticality stood for the living presence, whether it be human or such surrogates as corn and grain elevators. From the 1920s through the first half of the 1940s, the artist explored these antitheses with numerous variations, as his initially realistic figures and motifs gradually became more fragmentary and enigmatic. Another development – especially relevant for the composition of PH-306 – is that at a precocious stage Still pitted radiance against blackness, as if the two were in symbolic struggle. This went together with a tendency for his increasingly monstrous presences to simultaneously split apart and intertwine.

The signal strength of PH-306 lies in how these foregoing elements have been transformed to a degree where their representational roots are left far behind, resulting in an abstraction that is nevertheless imbued with traces of the former impulses. For example, note the emphatic uprightness of the canvas’s format itself, as though it held distant memories of Still’s assertion: “For in such a land [the Alberta prairies] a man must stand upright, if he would live”. In turn, the forms within the image echo this verticality as they rise up from what may well be a significantly earth-hued mass that spreads horizontally along the picture’s lower margin. Secondly, the rearing black and white areas interlock with a savage, claw-like violence, emphasized by their being delineated with raw strokes of the palette-knife.

Thirdly, this tendency to shred shapes and then embed them within each other – note how the leftward lemon passage and the dark gray at right are as immediately present as the central colors that they enfold like pincers – creates a wholly new kind of spatiality.

In short, PH-306 presents to the eye neither any conventional foreground nor background, but rather a vibrant continuum that owes nothing to precedents in even, say, Cubism.

As such, the logic reflects one of Still’s most passionate aims: “I’ve never wanted color to be color. I never wanted texture to be texture or images to become shapes. I wanted them all to fuse into a living spirit”.

In terms of chromatic organization, too, PH-306 is quintessential Still. Key bright notes galvanize somber tones – black, grey, brown and a subfusc maroon (top center). The former include the glaring white, the pale yellow in the upper left quadrant, the orange burst within it and especially the vivid yellow that snakes through the painting’s middle. The latter ranks among the artist’s most important devices, to which he gave the self-explanatory name, “life line”.

Like a vibrant artery, this life line (established long before Barnett Newman’s “zips”) distils the work’s energies into a single, brilliantly dynamic core. And overall, although PH-306 may at first appear relatively simple, the longer the viewer beholds its changeful drama the more it exudes an uncanny animation (not to mention the subtlest strands of blue that intensify the black pigment). Within the ostensibly sparse PH-306 much may be said to “happen.” Stealth incarnate.

“The best works are often those with the fewest and simplest of elements – pictures that are almost obvious, until you look at them a little more, and things begin to happen."

Several other factors also distinguish PH-306. Its modest dimensions belie the cliché that Still was first and foremost an exponent of outsize works in keeping with his penchant for the sublime and its association with overwhelming magnitude, and so forth. On the contrary, many Still paintings are in fact of modest size: for this very reason they gain in intensity. Consequently, rather than engulfing the spectator the tensions draw the gaze inward (he once mentioned “implosion” regarding his visual mechanics). In this respect, as a matter of record, in 1947 alone Still created at least twelve canvases of similar dimensions to PH-306; some are even smaller. Likewise, Still did not often date a work to two years, as inscribed on the verso of PH-306. When he did, it tended to signal a shift or progression in his evolution.

Accordingly, 1946-47 was indeed a turning-point when the residual figuration sometimes faintly evident in the former year segued to a radical non-objectivity by the end of the latter. It is not coincidence, then, that PH-301 in the major donation of thirty-three works that Still made to the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, in 1964 – the one canvas that most closely approaches the configuration of PH-306, including another snaking line, albeit there in darkest green and at lower right – should have been executed in the month of January 1947. On this count, it is the soul mate, or even bookend, as it were, to PH-306. Lastly, that Still gave PH-306 to his cherished daughter Sandra in 1976 to grace the wall of her Manhattan apartment surely reflects the fact that he accorded it a particular significance. In sum, PH-306 is therefore special, a most carefully considered and chosen achievement by one of the greatest American artists of the 20th century.