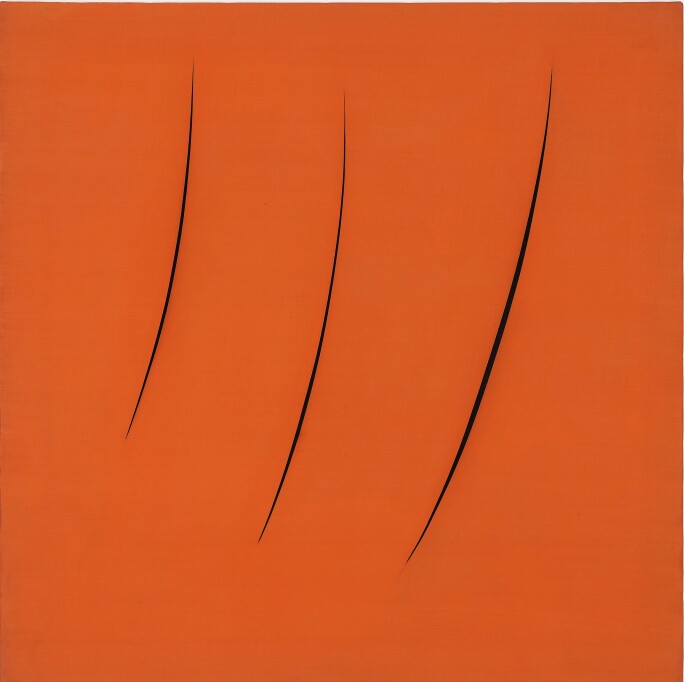

S o said the Argentinian artist Lucio Fontana of his best-known works, the monochrome paintings in which he cut long slashes that (with the help of some black cloth behind) seem to open up to an infinite darkness, what he called “a free space”. It was a seemingly destructive gesture that was actually a radically generative act.

The major exhibition Lucio Fontana: On the Threshold, opening at both the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Madison Avenue and Fifth Avenue locations on 23 January, constitutes the artist’s first US retrospective in more than four decades. Spanning work from some 37 years of the prolific artist’s career, the show presents paintings, sculpture, ceramics, drawings and installations, and will provide an opportunity for admirers familiar only with the slash paintings to learn the context for these dramatic works.

In fact, Fontana was 51 years old before he ever touched a canvas. He had worked in idioms ranging from funerary and abstract ceramic sculpture to architectural decoration, inspiring art historian Emily Braun to call him a “juggler” in an essay in the exhibition catalogue.

Presenting works like the deceptively simple slash paintings to a broad public presents a challenge, admits Iria Candela, the organiser of the show and the museum’s curator of Latin American art, but a welcome one. “I see this as a special opportunity to bring people on board and unpack these very enigmatic pieces,” she says, setting up the most ambitious of goals for the show. “How,” she asked:

do you make people really love Fontana in the same way they love Monet or Michelangelo?

One factor in Fontana’s stature is the way he carried on modernist traditions such as the challenging of distinctions between art mediums and the collapsing of boundaries between high and low. He also deeply inspired his contemporaries and forward-thinking younger artists; German artist Otto Piene, nearly 30 years his junior, called him “something like a spiritual father” of the Zero movement, which aimed to recreate art from a point zero and found inspiration in an artist who wouldn’t be restricted to any category.

One of the artist’s lesser-known but innovative idioms was installations incorporating architectural elements and dramatic lighting. These will get special attention even beyond the Met’s two venues: Spatial Environment, 1968, created for Documenta 4, in Kassel, will be on show at New York’s El Museo del Barrio from 23 January to 1 April, in a nod to his Latin heritage.

These innovations form a lineage for figures such as California Light and Space artists James Turrell and Doug Wheeler. In creating immersive environments that incorporated new mediums like neon lights (preceding artists like Dan Flavin and Bruce Nauman), Fontana reacted to new conceptions of space and technology. These were inspired by the scientific advances of the day – from the nuclear technology that delivered destruction on a previously unknown scale in the Second World War, to Yuri Gagarin becoming the first human to travel into outer space in 1961.

These multifaceted accomplishments have long made Fontana a market star as well as an important art-historical figure; since 2004, more than 200 works have sold for more than a million dollars at auction, fetching prices north of $20 million.

But if there are museum visitors scratching their heads at how these unconventional works can command such high prices, Fontana’s words may assure them that they’re not as offhand as they might seem. “They think it’s easy to make a cut or a hole,” the artist once said:

But it’s not true. You have no idea how much stuff I throw away. The idea has to be realised with precision.