1. Born Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech on 11 May 1904 in Figueres, Spain, Dalí would travel to Paris in 1929 and take up with the Surrealist group.

Expelled from art school after refusing to sit for his final exams, the young artist ventured to Paris where he met his idol Pablo Picasso, and befriended fellow Catalan artist Joan Miró. It was Miró who first introduced Dalí to Surrealist founder André Breton. Dalí was drawn to the group’s fascination with the subconscious and desire to create artwork that drew from the dream world.

2. His work was greatly influenced by Sigmund Freud’s theories on psychoanalysis and sexual repression.

As an art student in Madrid in the early 1920s, Dalí read Freud's The Interpretation of Dreams, which inspired the artist's interest in ideas of self-interpretation as a creative tool. Dalí finally met Freud in London in 1938 after Freud had fled Nazi-occupied Vienna. Dalí brought his painting The Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937) to the meeting. The author Stefan Zweig, along with patron Edward James who owned the painting, arranged the encounter, during which Dalí had the opportunity to sketch the famous Austrian psychoanalyst.

3. Dalí believed he was the reincarnation of his older brother, also named Salvador, who had died just 9 months before the artist's birth.

The specter of his brother haunted his existence and in 1963 Dalí painted Portrait of My Dead Brother. The family was plagued by loss. When he was sixteen-years-old, Dalí’s mother, an early supporter of his talents, died, an experience Dalí called “the greatest blow I had experienced in my life.”

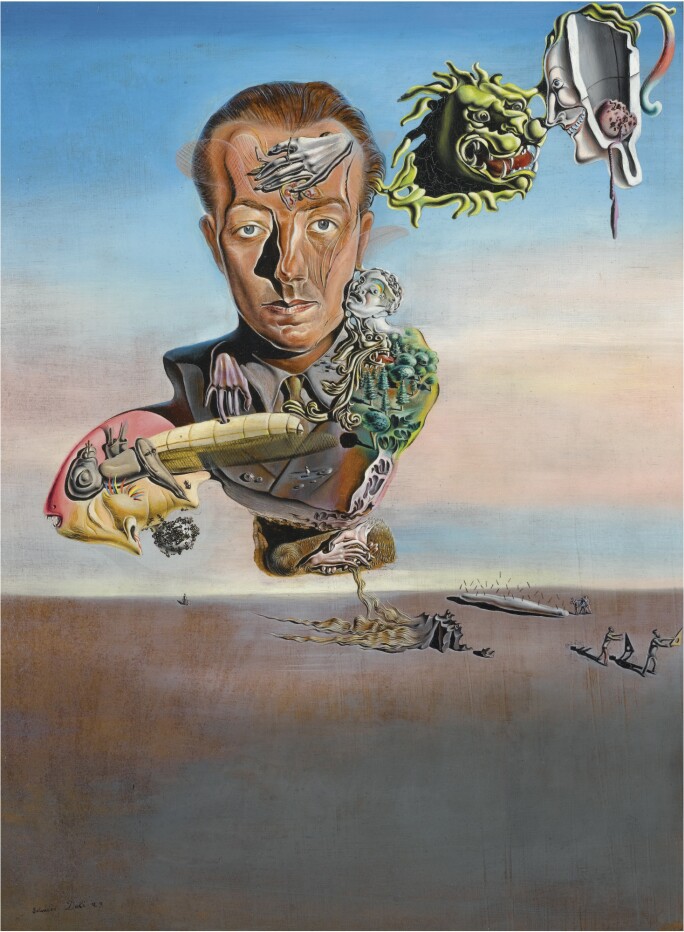

4. In the 1930s he developed his “paranoiac-critical” method, which allowed him to access his subconscious.

André Breton once described Surrealism as "pure psychic automatism." Breton encouraged and practiced automatic experiments in writing and drawing. Perhaps an early sign of the strained relationships to come, Dalí disavowed Breton's automatism favoring instead a more intentional approach to art making. In the early 1930s he developed his “paranoiac-critical” method, essentially an induced state of paranoia that allowed for the deconstruction of identity that encouraged the subjective mind to conjure links between otherwise disparate or unlikely objects.

"I would polish Gala to make her shine, make her the happiest possible, caring for her more than myself, because without her, it would all end."

5. The Surrealists later expelled Dalí for his glorification of Fascism and a perverse obsession with Hitler.

The Surrealists generally aligned themselves with a Marxist ideology and were horrified by Dalí’s continuous dalliance with authoritarianism and in particular his fascination with Germany’s führer. Dalí once remarked, “I often dreamed of Hitler as a woman. His flesh, which I had imagined whiter than white, ravished me…” This attraction translated into several artworks including his 1939’s The Enigma of Hitler. It was too much for the Surrealists who expelled him in 1939. Undeterred Dalí went on to praise Franco’s dominion over Spain during the 1940s.

6. Dalí met his future wife Elena Ivanovna Diakonova, known as Gala, while she was married to his friend the artist Paul Éluard.

Wed for forty-eight years from 1934 to 1982, they made highly unconventional pair. The Russian divorcée was ten years older than Dalí who was but the tender age of 25 when they met. Gala, who was still married to Éluard and engaged in a long affair with Max Ernst, left both, and almost immediately became the center of Dalí's world, acting as both his artistic muse and the manager of his exhibitions and sales. The idiosyncratic couple was in an open marriage, with Gala enjoying many encouraged affairs. At the time of death at age 87, she was romantically involved with 22-year-old Jesus Christ Superstar actor Jeff Fenholt. Dalí not only adored her, he was wholly dependent on her, saying once, "I would polish Gala to make her shine, make her the happiest possible, caring for her more than myself, because without her, it would all end."

7. He made most famous painting The Persistence of Memory Dalí when he was utterly penniless.

Scandalized by his relationship with Gala, Dalí’s father, a well-paid legal official , threw the 25-year-old painter out of the family home in Figueres. Shunned by the entire town, the artist moved to a shack in Port Lligat, a nearby fishing village. Completed when Dalí was 27, his famed painting derived its landscape from the terrain of Cap de Creus peninsular and the nearby Mount Pani. Some historians have suggested Dali’s melted clocks were inspired by Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity, though Dalí denied this association, instead citing the recollection of Camembert cheese he had seen melt in the sun. The painting was anonymously donated to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, where it remains a highlight of the collection.

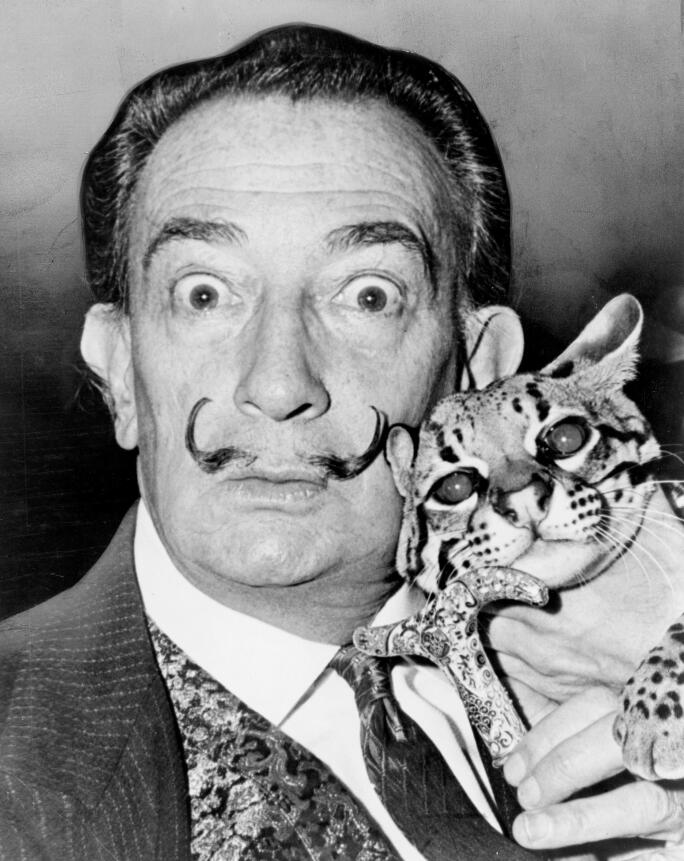

8. His iconic mustache had a literary inspiration.

Dalí’s upturned mustache may be the most famed facial hair of art history. A cultural emblem in its own right, the look has inspired quite a bit of speculation with some suggesting it is a tribute to Spanish Golden Age painter Diego Velázquez. However in a television appearance, Dalí stated plainly, "It's the most serious part of my personality. It's a very simple Hungarian moustache. Mr. Marcel Proust used the same kind of pomade for this moustache." Given that Proust’s seven-volume novel Remembrance of Things Past is a deep dive into childhood memory, indulgence and sexual frustration, the reference seems apt.

9. Sex frightened him, but was also his obsession.

Dalí’s fixation with sexuality dates back to childhood – fearing that he was sexually inadequate, or even impotent, the young Dalí became arguably addicted to masturbation, which was his primary, possibly only, vehicle of sexual expression into adulthood. Questions of homosexuality also swirled about the artist, with rumors that the Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca had tried to seduce him. It seems Dalí remained frightened by sex (of any orientation) for the entirety of his life — it is believe that he was a virgin when he met Gala at 25 and preferred voyeuristic pleasures (including hosting orgies) to consummation. These themes played out in many of his artworks, the artist saying, “Now sexual obsessions are the basis of artistic creation. Accumulated frustration leads to what Freud calls the process of sublimation. Anything that does not take place erotically sublimates itself in the work of art.”

Buñuel’s first film, the delirious cinematic experience has no definable narration or chronology, following a disjointed dream-logic with imagery of priests dragging donkeys bodies and a man wielding a razor at a woman’s eye. Though its overtly sexualized and disturbing imagery appalled some, it went on to run for eight months. Dalí would return to film again, collaborating with Buñuel once more on L'Age d'Or in 1930 and later with Alfred Hitchcock on the 1945 thriller Spellbound.

12. He had a pet ocelot named Babou.

He adopted Babou in the 1960s, and brought him everywhere with him including restaurants. He is also remembered for his pet anteater, which he took on walks through the streets of Paris and even brought him on an appearance of the Dick Cavett show.

13. He had a flair for fashion and collaborated with designer Elsa Schiaparelli.

While an art student Dalí would dress like a English Dandy and throughout his life he was known for his signature, eccentric style. Speaking of this interest, he mused, “the constant tragedy of life is fashion.” During the 1930s he became beguiled by the designs of Elsa Schiaparelli, with whom he would collaborate on several jaw-dropping designs including a white dinner dress emblazoned with a giant lobster, which was inspired by his lobster rotary phones, as well as a shoe-shaped hat.

14. Money delighted him and he went to excessive lengths to acquire it.

It was André Breton who disparagingly nicknamed Dalí “Avida Dollars,” an anagram of his name meaning approximately “eager for dollars.” It is well known that Dalí refused to pay for meals, doodling on the backs of his checks so that that they would never be cashed. He also engaged various commercial enterprises including advertisements for Lanvin chocolates as a means to support his and Gala’s extravagant spending habits.

15. He designed a jeweled-ruby heart that actually beats.

Dalí collaborated on a line of jewels called Dalí-Joies with the American millionaire Cummins Catherwood, combining Dalí’s designs with jewels provided by Catherwood. The collection's piece-de-resistance is The Royal Heart, a ruby, diamond and emerald encrusted corazón, which, somewhat disconcertingly, beats. The startling piece is now in the collection of the museums of the Salvador Dalí Foundation, based in his hometown of Figueras, Spain.

16. He had a phobia of grasshoppers.

He was so frightened by grasshoppers as a child that his classmates would throw them at him to torment him. It is believed he may have suffered from Ekbom’s syndrome, a delusional belief that insects are under one’s skin. When grasshoppers appear in his oeuvre, they symbolize plague, decay and death. Other recurring symbols in his iconography included ants, lobsters, eggs, snails, elephants and chests of drawers which each possessed their own psycho-sexual significance.

17. Dalí reached the heights of his fame in America, though his critical reception during these years cooled.

Dalí and Gala began to regularly travel to the United States during the late 1930s and the couple made the United States home during World War II from 1940 to 1948, living primarily in New York. Dalí became a figure of popular culture — publishing a sensational autobiography as well as participating in several Hollywood endeavors. The art world, however, increasingly viewed him as a commercial artist and his work was greeted with tepid enthusiasm and, often, outright suspicion. The New York Times summarized his time in the United States saying, “Where the other Surrealists remained essentially private people, Dali was a born performer, a man who needed an audience and responded to it. He found that audience in America, and for many years he kept it impressed and amused.”

18. In the post-war years, Dalí developed a new style he dubbed “Nuclear Mysticism,” which claimed to view religion through a scientific lens.

Having returned to Spain he cultivated a new style that combined the ideas of contemporaneous science with Catholic religious imagery, as seen in such works as The Sacrament of the Last Supper (1955) and The Ascension of Christ (1958). Such images, though dream-like in execution, would have been thematically acceptable under Francisco Franco's conservative regime. In 1949 Dalí, a former atheist, had a private audience with Pope Pius XII where he presented his painting The Madonna of Port Lligat – which depicts Gala as the Madonna – to be blessed by the pontiff. The styles and aesthetics of these works harken to Renaissance Masters including Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo.

19. Dalí and Gala grew estranged in their last years, but when she died in 1982 at the age of 87, he was cast into a state of maniacal panic and deep depression.

The pair had always had an unusual union, however, tensions grew fraught late in life, with Dalí increasingly paranoid his wife would abandon him and angered by the lavish gifts she bequeathed upon her various lovers. In 1968, Dalí had purchased a castle in Púbol, Spain, as a retreat for Gala and she soon began to live there for several weeks at a time with Dalí only able to visit her by invitation. Relations became so rancorous that Dalí at one point physically assaulted his muse and manager, breaking two of her ribs. She, in an attempt to calm him, administered Dalí large quantities of Valium and other drugs, which nearly killed him. Despite such antipathy, when Gala passed away, Dalí fell into a state of deranged despair, refusing to eat and scratching at his face.

20. Ill, bedridden and depressed, Dalí lived in last years in isolation at his castle in Púbol, Spain.

The artist lived on seven unhappy years after Gala’s death. Forced to retire from painting because of palsy, his health and mental state continued to deteriorate for the remainder of his days. A demanding invalid, he verbally abused his nurses. In 1984 a mysterious short-circuit in his call button set a fire that severely burned the artist’s leg.

21. After a prolonged legal battle in which a Spanish fortuneteller claimed to be Dalí’s daughter, the artist’s body was exhumed in 2018 for paternity testing.

Dalí died of heart failure on 23 January 1989 and was buried in a crypt he designed at the Dalí Theatre-Museum in his hometown of Figueres, Spain. In the aughts, the fortune-teller Pilar Abel filed a suit claiming to the product of a 1955 liaison between the artist and her mother. After DNA taken from skin and hair traces from his death mask proved inconclusive, his body was exhumed for testing — the results proved Adbel was not Dalí’s child. Narcís Bardalet, the embalmer who prepared Dalí’s body after his death in 1989, exhumed his remains and noted, with some glee, that the artist’s mustache was in excellent condition.