1. Although he was uncomfortable aligning himself with “isms,” Miró is regarded as one of the most important Surrealists.

Shortly after moving to Paris in 1920, Miró befriended André Breton,Max Ernst, Jean Arp, André Masson and others associated with Dada and Surrealism. While he felt an affinity with Bréton’s concept of “psychic automatism” – a practice Miró would incorporate throughout his long career – he was less interested in manifestos. Nevertheless, he participated in the first Surrealist exhibition in 1925, and Bréton hailed him as “the most Surrealist of us all.” Indeed, Miró’s fantastical symbolic language of semi-abstracted, biomorphic forms and his innovative use of line, shape and color represent some of the most significant contributions to the Surrealist oeuvre.

2. An erstwhile accounting clerk, Miró devoted himself to art after suffering a nervous breakdown.

While he began studying fine arts at an early age, Miró’s parents hoped that their son would pursue a career in finance. Thus, at age 14, he enrolled in business school (concurrently studying art at La Lonja’s Escuela Superior de Artes Industriales y Bellas Artes). Upon completing his studies, Miró took a position as an accounting clerk, but did not fare well in the office environment; he reportedly suffered a nervous breakdown, followed by a bout of typhoid fever. After a period of convalescence at his parents’ Mont-roig estate, Miró recommitted himself to his artistic studies, enrolling at Francesc Galí’s Escola d’Art from 1912-15.

3. His first gallery show was a disaster

Miró’s studies with Francesc Galí brought him into the orbit of the Galeries Dalmau, a burgeoning artistic center in Barcelona. Gallery owner José Dalmau was an early supporter of the young artist, giving Miró his first solo show in 1918. Featuring works indebted to the Fauves and Cézanne, the exhibition was panned by critics and the public alike; not a single painting was sold. The disastrous reception eventually prompted Miró to leave Barcelona for Paris in 1920.

4. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he disliked art critics.

Speaking with biographer Walter Erben, Miró expressed a withering opinion of those he described as “more concerned with being philosophers than anything else. They form a preconceived opinion, then look at the work of art. Painting merely serves as a cloak for their emaciated philosophical systems.”

5. He sold a painting to Ernest Hemingway.

The culmination of his growing stylistic departure from the post-Impressionist influence, Miró considered The Farm (1921-22) his first masterpiece – a sentiment which was wholeheartedly shared by his friend Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway purchased the painting in 1925, later remarking: “I would not trade it for any picture in the world. It has in it all that you feel about Spain when you are there and all that you feel when you are away and cannot go there. No one else has been able to paint these two very opposing things.” One of his first paintings to celebrate his Catalan identity, Miró’s depiction of his family farm in Mont-roig is remarkable for its unique amalgamation of carefully observed realist detail within the abstracted spatial vocabulary of Cubism.

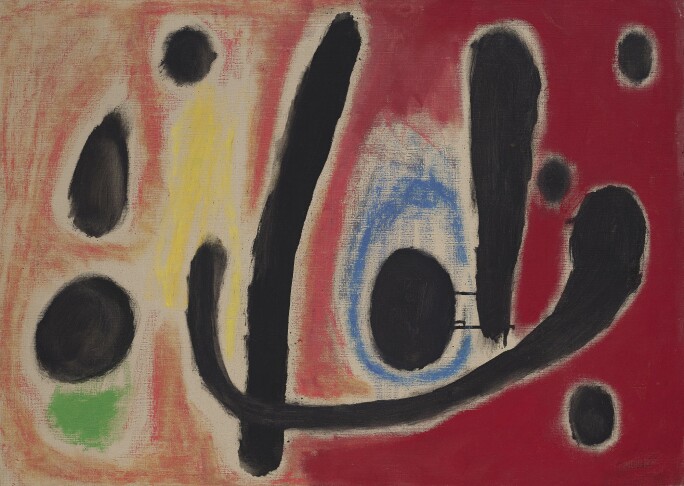

Works by Joan Miro at Sotheby's

6. Taking inspiration from old masters, his Dutch Interiors exemplify what art historians have dubbed the artist’s skill of “mirómorphosis.”

Following a successful 1928 exhibition in Paris, Miró remarked: “I understood the dangers of success and felt that, rather than dully exploiting it, I must launch into new ventures…I feel a great desire to put off those who believe in me.” Soon thereafter, he visited the Netherlands for the first time, gravitating toward the genre paintings of Jan Steen and Hendrick Sorgh. Returning home with postcards, he created his own interpretations of the old master works, transmuting traditional elements into an ambiguous biomorphic fantasia.

7. Miró famously declared: “I want to assassinate painting.”

Quoted in 1927, the artist’s contempt for bourgeois aesthetic conventions launched a creatively fecund period of rapid-fire experimentation with “anti-painting”, collage and assemblage. Using mass-produced and industrial materials, Miró sought to reinvigorate his practice through experimentation in a wide variety of media, a pointed rebuke to what he saw as the commercialization and politicization of established painting. He was particularly critical of Cubism – by that time, a widely accepted mode of expression— once stating: “I will break the guitar” (in reference, of course, to the popularity of Picasso).

8. Fittingly, his practice encompassed a dizzying variety of media.

From collage and sculpture to prints and wood reliefs, Miró experimented tirelessly throughout his career. In 1944, he embarked upon nearly three decades of collaboration with ceramicist Josep Lloréns Artigas, producing numerous vases, sculptures and murals. Around this time, he also began experimenting with lithography and etching, and from 1954-58, concentrated almost exclusively in ceramics and prints. Working well into his old age, Miró’s artistic curiosity and inventiveness never ceased; in 1974, he was commissioned to create a monumental tapestry for New York’s World Trade Center, which hung the lobby of the South Tower until it was destroyed in the September 11th attacks of 2001.

9. He was married for over 50 years.

Miró knew Pilar Juncosa from childhood; his mother and hers (a cousin of Miró’s grandmother) were brought up together when the latter was orphaned. Miró and Juncosa married in 1929, and the following year, their only daughter, Maria Dolors Miró, was born. The two remained together until his death in 1983. Of his wife, Miró once said: “[She] is the ideal companion for me. Without her, I have no idea of anything or how to organize things. She is my guardian angel.”

10. The Spanish Civil War kept him from returning home—and revealed a political side to his work.

Miró was visiting Paris with his family in 1936 when the Spanish Civil War broke out. Unable to return to Barcelona, Miró found himself “paralyzed by the general feeling of terror,” and described feeling “uprooted and nostalgic for my country.” While he had previously avoided explicitly political themes in his work, this tumultuous period revealed his support for Spain’s Republican government and opposition to Franco. In 1937, Miró was commissioned to decorate the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World’s Fair (along with Picasso, who created Guernica in response to the bombing of the town of the same name), painting The Reaper (Catalan Peasant in Revolt). The monumental mural, depicting a powerful figure wielding a sickle, was lost or destroyed the following year; only a few black and white photographs survive today.

11. Miró was uprooted by conflict for a second time during World War II.

At the outset of World War II, Miró and his family were living in Normandy, having left Paris in 1939. As Nazi forces began invading France, he found himself retreating to a uniquely private universe in his art. During this period, Miró embarked on a series of gouaches known as the Constellations, featuring birds, stars and other motifs evoking flight and escape. In 1940, Miró and his wife and daughter fled to Spain, the paintings rolled under his arm. The series, exhibited in New York in 1945, were among the first artistic documents from Europe to reach America after the war.

12. He designed sets, costumes and props for the Ballets Russes.

In 1926, Ballets Russes founder Sergei Diaghilev orchestrated a surrealistic production of Romeo and Juliet, engaging Miró and Max Ernst as designers. The ballet— considered bourgeois by Bréton and other die-hard Surrealists— was met with protest when it opened in Paris. The ballet’s composer, Constant Lambert, also disapproved of the artists’ participation, though for different reasons; he berated the nontraditional production design as the work of “tenth-rate painters from an imbecile group called the Surrealists.” The experience did not deter Miró, and in 1932, he reprised his role as a designer for a production of Jeux d’enfants, mounted by the Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo.

13. Miró’s famous ‘dream paintings’ were the result of hunger-induced hallucinations.

As a struggling young artist living in Paris in the mid-1920s, Miró described “hallucinations of hunger” giving rise to opaque shapes and delicate linear forms on open fields of blue. Departing from the figurative style of his earliest work, Miró’s output from 1925-27, sometimes described as “poetry-paintings,” evoked the enigmatic world of dreams.

14. One such painting, Peinture (Etoile Bleue) (1927) sold at auction for £23.5M ($37M USD) in 2012, a record for the artist.

Executed at the height of Surrealism, the painting is a striking example of Miró’s pioneering style of poetic abstraction. The extraordinary image, featuring the rich ultramarine blue emblematic of his ‘dream paintings,’ represents a high point of the artist’s early career.

15. Born in Barcelona, Miró’s artistic perspective was intimately tied to his Catalonian identity.

Although he lived in Paris for several years and spent his late career in Palma de Mallorca, Miró remained devoutly committed to his Catalan roots. Coming of age during the Catalan Independence movement, politics and questions of national identity were inescapable. Using the image of a Catalan peasant as an alter-ego of sorts, Miró expressed his deep connection to his homeland: in The Hunter (1923-24), the titular figure, wearing a traditional red barretina, floats across a landscape evoking elements of the family farm in Mont-roig, with French, Catalan and Spanish flags in the background. The iconography appears in numerous other works, including Head of a Catalan Peasant (1924-25).

16. In 1975, he helped found the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona – but he hated the name.

The foundation, located on the mountain of Montjuïc, became a repository for much of Miró’s work, and continues to honor the artist and his legacy. However, his primary aim in establishing the museum was to promote the work of young experimental artists. Miró disliked the name and hoped that the Foundation would serve as “a pretext for those who come after,” rather than a monument to his own body of work. Today, the museum’s Espai 13 is dedicated to exhibiting the work of emerging artists; the permanent collection includes numerous pieces by Miró, as well as works by Alexander Calder, Mark Rothko and René Magritte.

17. His personality stood in stark contrast to his playful artistic style.

Modest, introverted and hardworking, Miró evoked nothing of the bohemian artist in his outward presentation. Habitually clad in dark business suits, he was known to be taciturn and disciplined, with his friend and biographer Jacques Dupin remarking on his ability to conduct a life “utterly free of disorder or excess.”

18. Miró gained wide international fame after WWII…

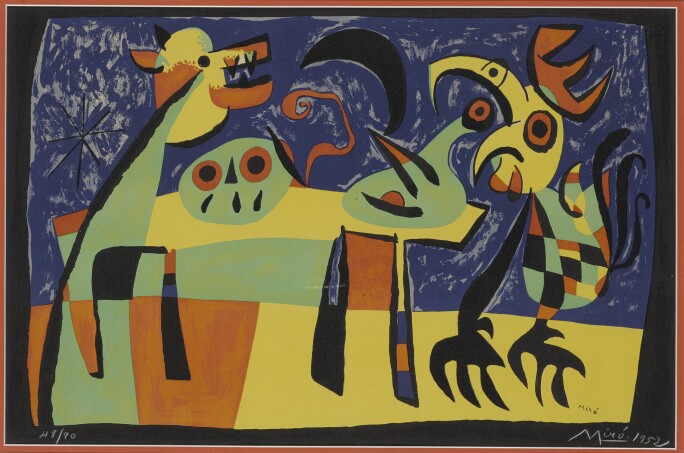

In the post-war period, Miró cemented his status as one of the most important artistic voices of the 20th century. He completed numerous important commissions, including a ceramic mural for the UNESCO building in Paris for which he won the Guggenheim International Award (1958). He was also honored with the Grand Prize for Graphic Work at the 1954 Venice Biennale, and was included in the first documenta exhibition in Kassel the following year.

19. …Enabling him to create the studio of his dreams.

Thanks to international success, Miró was finally able to enjoy financial stability. While known for his modesty, the post-war increase in the value of his art prompted Miró to negotiate with gallerists, declaring: “What I will no longer accept is the mediocre life of a modest little gentleman.” In 1956, he commissioned architect Josep Lluís Sert to build an ultra-modern studio in Palma de Mallorca, which he used for the remainder of his life. Today, the studio is open to the public as part of the Fundació Pilar i Joan Miró.

20. He worked up until his death at the age of 90; the monumental public sculpture Woman and Bird (1982) is the artist’s last great work.

The colossal 66-foot-tall sculpture, commissioned as one of Barcelona’s first major public art projects following the re-establishment of democracy, rises from the reflecting pool of the Parc de Joan Miró. Emerging from the artist’s unique iconographic universe, the suggestively phallic form features a long vertical incision that clearly alludes to the femininity of its subject. The sculpture was dedicated in 1983, just months before Miró’s death.

21. Miró’s artistic legacy is one of the most influential and far-reaching.

His innovative and experimental practice informed the work of Surrealist contemporaries, including Max Ernst, Yves Tanguy, and Salvador Dalí, and longtime close friend Alexander Calder credited Miró as a defining influence. His work is widely regarded as one of the most important precursors to Abstract Expressionism and Color Field painting, influencing Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, Arshile Gorky, Roberto Matta and Jules Olitski. When Miró died in 1983 at the age of 90, he was remembered in his New York Times obituary as having left an “ineffaceable mark upon his century.”