1. Caspar David Friedrich was the son of a candle-maker and soap-boiler. He was the sixth of ten children.

2. He was born in Greifswald, a harbour town in Pomerania on the Baltic coast.

3. Friedrich studied at the University of Greifswald (whose art department is now named the Caspar David Friedrich Institut) before moving to the Academy of Copenhagen and then settling in Dresden, where he died in 1840.

4. Friedrich was elected a member of the Berlin Academy in 1810, after two of his paintings were purchased by the Prussian Crown Prince.

5. In 1816, however, Friedrich applied for Saxon citizenship in an effort to distance himself from Prussian authority, a surprising move given the Saxon government’s pro-French stance and Friedrich’s paintings’ patriotic and anti-French stance.

6. In 1805 Friedrich won the Weimar art competition, organised by the writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

7. Friedrich’s popularity waxed and waned over his lifetime. Though he gained early renown, this was lost over his later years. Friedrich died in obscurity, and it was not until the 1970s that he came to favour once more.

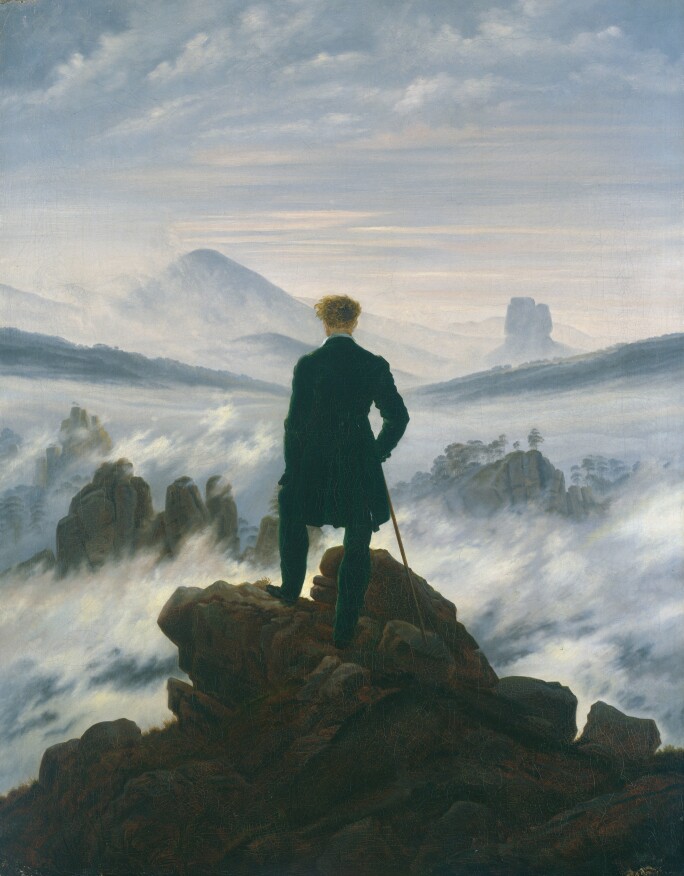

8. Friedrich is recognised chiefly for his allegorical landscapes. Common features of these include contemplative, silhouetted figures, night skies or morning mists, barren trees and Gothic or Megalithic ruins.

9. The most radical achievement of Friedrich was his new approach to pure landscape imagery. The landscape became the protagonist rather than the human/s within it.

10. Friedrich followed in the footsteps of German Romantic writers and critics such as Novalis, the Schlegel brothers and Tieck, who brought a new emotive awareness to nature.

11. Like his contemporaries J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, Friedrich depicted nature as a divine creation that stands in opposition to the artifice of the man-made world.

12. Friedrich famously once said “The artist should not only paint what he sees before him, but also what he sees within him.” In his eyes, contemplation of and emotional response to nature was of primary interest.

13. Friedrich has influenced many notable artists, including his contemporary Johan Christian Dahl, and the more modern Gerhard Richter, Mark Rothko and Arnold Böcklin.

14. After wedding Caroline Bommer in 1818 (with whom he had three children), Friedrich’s paintings saw use of a brighter and less austere palette and conveyed a sense of levity. Frequency of human presence in these paintings also increased considerably during this period, which perhaps reveals the new importance of his personal life after starting a family.

15. The Nazi party had used Friedrich’s work to promote their ideology, attempting to associate him with their nationalistic slogan Blut und Boden. This led to a decline in Friedrich’s popularity during the post-war period.

16. Friedrich’s first major work, Cross in the mountains (which is now named Tetschen Altar) was initially received coldly. Nevertheless, it received wide publicity.

17. In his final fifteen years of life, Friedrich’s reputation went steadily into decline. He was thought to be too eccentric, melancholic and out of touch with the times.

18. Though the model of Wanderer above the sea of fog (pictured below) remains a mystery, art historian Joseph Koerner wrote in Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape that the figure in question may be a Colonel Friedrich Gotthard von Brincken, a high-ranking forestry official. His clothing, Koerner claims, suggest that he is a volunteer ranger for the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III’s war against Napoleon. Koerner writes: “Von Brincken was probably killed in action in 1813 or 1813, which would make the 1818 Wanderer above the Sea of Fog a patriotic epitaph”. Consequently, the work could be seen as a subtle celebration of victory over the French and an illustration of German nationalism and Prussian unification.

19. Friedrich suffered his first stroke in 1835. From this point on, he suffered minor limb paralysis which reduced his dexterity. This limited him to watercolour, sepia and reworking older compositions.

20. Though Friedrich’s works are undoubtedly imbued with a sense of melancholy and gloom, this feeling is contemplative. That is, graves, funerals, ruins and other such imagery point to a more peaceful life beyond human mortality. The consolation of eternity is present even in his most sombre works.

21. By 1820, Friedrich was living as a recluse. His friends called him “the most solitary of the solitary”. He died in relative poverty.