Several key events occurred just after a decade of the Qianlong Emperor's reign that would make the year a turning point of the Qing dynasty. We take a close look at an important work of calligraphy and landscape painting, The Mid-Autumn Festival at the Imperial Garden, to understand what brought about the beginnings of a new era for the empire.

I n eleventh year of his imperial reign (1746), the Qianlong Emperor changed the name of his study to the “Hall of the Three Rarities” (Sanxitang), located in the western section of the Hall of Mental Cultivation. It was so named because the rarities refer to three masterpieces of calligraphy – Wang Xun’s Letter to Boyuan, Wang Xizhi’s Timely Clearing After a Sudden Snow, and Wang Xianzhi’s Mid-Autumn Manuscript – works that the Qianlong Emperor had in that year come to appreciate and held a special significance to him. That hall would house the Emperor’s collection of most treasured paintings and works of calligraphy. The eleventh year would prove to be a consequential moment in the Qianlong Emperor’s reign. In the second month of that same year, to mark the importance of this treasury, the Emperor directed the imperial court painter Dong Bangda (1696-1769) to work on Memories of the Hall of the Three Rarities. What Dong created was the image of a scholar practicing calligraphy amidst an alpine forest, a painting that immortalised the Hall of the Three Rarities as a haven for literary cultivation. The Qianlong Emperor was immensely pleased.

Landscapes by Dong Bangda

Dong Bangda was certainly no average court painter. A native of Fuyang, Zhejiang province, he was a scholar of the highest order and attained the prestigious rank of Minister of Rites. His landscape paintings were influenced by the Yuan dynasty (1271 – 1368) masters, and he excelled at landscape painting techniques. Not only did he paint for the imperial court, but he also edited and compiled the The Precious Collection of the Stone Canal Pavilion (Shiqu baoji), an extensive catalogue of painting and calligraphy in the imperial collection. Within the three volumes of Shiqu baoji, Dong’s own works numbered almost 200, most of which bore calligraphy by the hand of the Qianlong Emperor, a sign of appreciation.

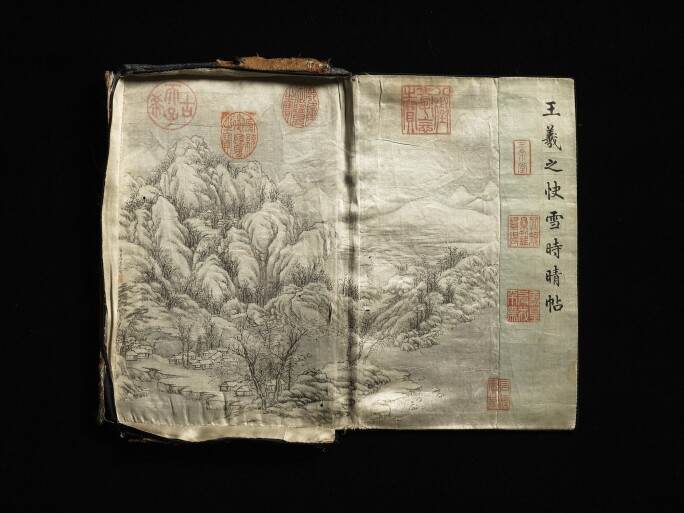

At the behest of the Qianlong Emperor, Dong Bangda also added to the works known as the “Three Rarities” (Sanxi tie). In an epilogue to Wang Xun’s Letter to Boyuan, Dong annotated and painted a refined image of a recluse standing upon a cliff and looking off into the distance. According to a work by the literatus Shen Deqian, Dong must have painted this landscape no later than the third month of the eleventh year of the Qianlong reign. In the album leaf for Wang Xizhi’s Timely Clearing After a Sudden Snow (Kuaixue shiqing tiece), Dong Bangda painted an alpine landscape on the custom-made silk cover, depicting branching trees covering the base of an imposing snow-capped mountain range. Created to suit the Emperor’s taste, these pieces were imperial commissions overlaying interpretations of the original works.

Appreciation of the 'Mid-Autumn Manuscript'

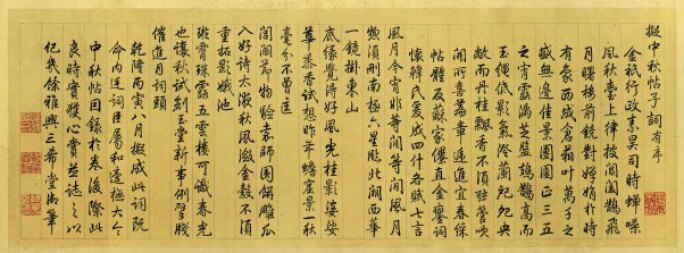

Later the same year, as it approached the Mid-Autumn Festival, the Qianlong Emperor saw fit to show his appreciation of Wang Xianzhi’s Mid-Autumn Manuscript by writing a poem inspired by the original, and modelled after the rhyme, metre and structure. The Emperor’s calligraphy Preface to Poems in Imitation of the Mid-Autumn Manuscript was mounted after Mid-Autumn Manuscript as a commentary. As part of the proceedings, the Emperor later had Dong Bangda paint a work based on Preface to Poems in Imitation of the Mid-Autumn Manuscript and to accompany the response poems by the court scholars. Inspired by the Mid-Autumn Manuscript, this gathering yielded a separate work of art The Mid-Autumn Festival at the Imperial Garden – showcasing the poetry of brush and ink expressed by hands of the Qianlong Emperor and Dong Bangda.

“In the eighth month of the eleventh year, I, the Qianlong Emperor, emulated this poem, then instructed court scholars to compose responses. The Emperor’s poem was appended to the end of the Mid-Autumn Manuscript scroll. This marks an excellent moment, and I have truly admired and recorded them as mementos of the aesthetic mood. Written by the Emperor in the Hall of the Three Rarities.”

Four large characters “Guang Han Qing Zhao” opens the work. These were written by the Qianlong Emperor, meaning “The moonlight spreads, cool and bright.” The graceful brushstrokes of these words were painted on a wave-patterned paper expressly made for the Qing rulers. The following section is the Preface to Poems in Imitation of the Mid-Autumn Manuscript written by the Emperor on ancient sutra paper, which was a very rare and precious material that he favoured for his own calligraphy. The painting by Dong Bangda follows the preface, and then the final part comprises poems composed by court officials which were rewritten down on the scroll by Wang Youdun, who was the Minister of Justice (xingbu shangshu) at the time.

Dong Bangda landscape is highly refined, with fine outlining and superior ink tone. Dong favoured a light touch with textured and rubbed strokes, which would appear denser or more compact at times to correspond to the Qianlong Emperor’s poem. The poetry and the painting resonate together in an ingenious way.

The works derived from the Three Rarities – The Mid-Autumn Festival at the Imperial Garden and the pieces associated with Letter to Boyuan and Timely Clearing After a Sudden Snow – should be considered as an integrated whole in order to get a comprehensive understanding of the creative direction and quality of the works. They were all painted by Dong Bangda with brush and ink to express the Qianlong Emperor’s high regard for the Three Rarities, and they represent the very peak of Dong’s career achievements.

The Qianlong Emperor’s Administrative Ambitions

According to Imperial Diaries of the Qianlong Emperor (Qianlong qiju zhu), the Qianlong Emperor celebrated the Mid-Autumn Festival during the eleventh year of his reign in the convivial company of the imperial family, nobles, and ministers. After the holiday feast on this momentous year, he composed Preface to Poems in Imitation of the Mid-Autumn Manuscript, and then had scholar-officials write response poems of their own, which were selected and added to the end of the present work.

The Qianlong Emperor’s poetic preface evokes a land of peace and prosperity – full of beautiful scenery, lively atmosphere, and celebrations of song and dance. It was a purposeful initiation of a new form of “elegant scholarly gathering” (yaji) at court, in which court scholars would compose new poems for the Mid-Autumn Festival inspired by the Emperor’s lead; in the response poems, the final word of each line – except the third, seventh, eleventh, and fifteenth – must mirror the Emperor’s. The nine response poems were compiled and written at the end of the scroll by the calligraphy of Wang Youdun. Their poetry portrayed festive scenes of Mid-Autumn celebrations, extolled the Emperor’s leadership, and emphasised the collegiality of assembled ministers writing poetry together. The subtext was the dawn of a new kind of governance, exemplified by the scholarly gathering of poetry and painting that would become a set tradition for the next fourteen years.

The Qianlong Emperor would reprise the Mid-Autumn scholarly gathering nine more times in the fourteen years that followed until the 25th year of his reign. Each time, he would compose a different poem with the identical end rhyme of his previous poems, an iteration of the original, preceded by a short preface describing the beautiful scenery in front of him, and commemorating key contemporary events and achievements of a prosperous empire. Following several days of banquets in appreciation of the moon, he would gather scholars and painters for this new Mid-Autumn tradition at court. In some years, during occasions of disaster or mourning, there would be no such celebration. The tradition carried on until ten years of these iterative poetic works were completed, all of which were recorded in the The Precious Collection of the Stone Canal Pavilion: Series Three (Shiqu baoqi sanbian). During these fifteen years, this practice brought the Emperor and his officials closer, strengthening their relationship and demonstrating the Qianlong Emperor’s paternal love for his ministers.

The Start of a New Era

The Mid-Autumn Festival at the Imperial Garden represents an important turning point of the Qianlong Emperor’s reign, coming at just past the ten-year mark of his rule, and emblematic of his engagement with his high-ranking ministers. For the subsequent fifteen years, the empire would be characterised as a period of peace and prosperity, an abundance brought about by upstanding officials and, above all, a sage ruler to lead his subjects. Opening the second decade of the Qianlong Emperor’s rule, the year represented the formal beginning of a new era. In the first month of that year, he declared a general amnesty and exempted the people of all provinces from land taxes to mark the decennial of his ascendance to the throne. The works that inspired the Hall of the Three Rarities reflect the conviction of the Qianlong Emperor, then just age 35, in ushering in a grand vision and a new direction for the empire.