Auction Highlights

Faces of The Last Supper: The Influence and Legacy of Leonardo Da Vinci’s Masterpiece

Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper is one of those works of art that needs little, if any, introduction – an icon within the canon of Western art, which bridges the realms of fine art and popular culture. The mural itself, executed in the late 15th century in the refectory of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan, represents the scene of the Last Supper of Jesus with the Twelve Apostles and specifically depicts the drama-laden moment after Jesus announces that one of his Apostles will betray him. Beyond the technical accomplishments of the work, such as Leonardo’s mastery of perspective and the simple yet groundbreaking arrangement of figures, lies a profound and complex display of human emotion. Leonardo focuses on the differing temperaments of the Apostles, highlighting their varying degrees of anger, angst, fear and inquisitiveness, displaying these emotions in the most compelling of manners through their facial expressions, poses and hand gestures.

The influence that the Last Supper has had on later generations of artists cannot be overstated. Rubens and Rembrandt were both profoundly affected by its composition, and also by its extraordinary narrative quality, and the Last Supper has also filtered its way into the 20th Century through Andy Warhol’s series of silkscreen paintings, executed shortly before his death in 1987. But long before Rubens, Rembrandt and Warhol, came Leonardo’s own assistants, with the likes of Giampietrino and Andrea Solario both making important painted copies of the Last Supper (circa 1520). Given that the condition of the mural painting itself began to deteriorate rather soon after it was executed, the early copies made by Leonardo’s pupils are a precious indication of how the masterpiece must originally have looked.

Sotheby’s Old Master Drawings Department is excited to be offering for sale this July two early drawn copies attributed to another of Leonardo’s assistants, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio. These monumental studies in coloured chalks are moving and highly significant contemporary records, drawn actual size, of the immensely expressive individual heads of the Apostles in the Last Supper. The drawings correspond closely to the heads of two of the apostles to the left of Christ, depicting: The Head of Saint John the Evangelist with the profile of the Head of Saint Peter to the left and The Head of St. James the Less with the indication of the right shoulder and the open hand of St. Andrew. They are part of a well-known series of eleven similar sheets scattered in museums and private collections, drawings which together passed over the centuries from the collection of the great English connoisseur Sir Thomas Lawrence to that of King William II of Holland, and then to the Grand Dukes of Saxe-Weimar, before being dispersed.

A Tough and Ingenious Breed - The Artist / Traveller

‘Intrepid traveller’ and ‘ground-breaking artist’ are not necessarily two phrases that one would immediately think of pairing together. However, a closer look at the art history books reveals otherwise and – by chance – this auction includes a number of very fine drawings that prove the point.

Take, for example, Abraham Rutgers (see lots 27 & 28), who made the journey from his home in Holland to England in the 1660s. True, people did travel backwards and forwards between the two countries regularly, but it still took courage to cross the north sea (with its unpredictable weather) and travelling by road was far from comfortable – many routes were little more than pot-holed tracks and it was not until the 1680s, when glass was introduced to carriage windows, that some protection from the elements was afforded!

In the 18th century the ‘Grand Tour’ to Italy became fashionable. Men such as William Marlow (see lot 50), who was on the Continent in the late 1760s, covered the distance between London and Rome by carriage, except, of course, in the Alps where - because there were no coach roads - travellers were hoisted onto ‘Swiss’ chairs and carried across the mountains. This part of the journey took eight days.

Getting anywhere during this period was simply very time consuming. If it took Marlow over a week to cross the Alps, then, when Thomas and William Daniell (see lots 49, 62 and 68) decided to go to India in 1785, it took them the best part of a year, before they arrived at their destination, Calcutta, via Whampoa in modern day China. Their extensive tours in north, south and western India were an extraordinary achievement, in total they were ‘on the road’ for over four years and they often found themselves travelling through hazardous and little known (to European) regions, where they were at the mercy of local guides, the often hostile climate and the exotic food. The very real danger that they were exposed to is illustrated when one learns that - while travelling down the mighty Ganges - their baggage-boat (which was carrying all their belongings, excluding their precious drawings) capsized and was washed away.

As well as being patient and brave, artists / travellers needed to be organised and resourceful. In the 19th century, Edward Lear, for example, was a ‘serial’ traveller, carrying out over 40 sketching tours during his long life, to countries as far apart as Sicily and Sri Lanka (see lots 63 & 64). Lear would meticulously plan these trips, always ensuring that he had read everything he could find about the places he intended to visit. Often travelling on a ‘shoestring’, he needed to be self-sufficient, carrying not only his artist materials, but also (when the situation required) a tent, cooking things, medicines and even a gun.

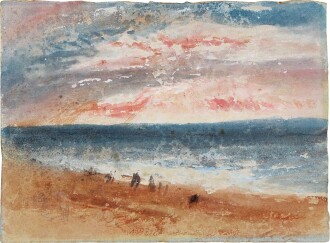

As the 19th century progressed, better roads and the invention of the steam engine made travel quicker and easier. However, artists / travellers still needed to possess steely determination and boundless energy. Joseph Mallord William Turner’s industrious output illustrates this: thousands of watercolours and drawings survive in sketchbooks, or as loose sheets, in the Turner Bequest at Tate, Britain. He spent a life-time on the move, relishing the opportunity of trekking up little known Alpine valleys (see lot 61) or following mighty rivers in search of the sublime and the beautiful. Turner was not a man to give in easily and in his youth, he must have been extremely fit!

Part of the thrill of working with early drawings and watercolours is the knowledge that you hold something that was created in a world very different from our own and that has survived the centuries. Considering for a moment why, how and where an artist created a work often leads to a new sense of admiration and wonder. If an artist wanted to succeed as a painter of landscapes, they needed to open the studio door and step outside.