Arts of the Islamic World & India including Fine Rugs and Carpets

Arts of the Islamic World & India including Fine Rugs and Carpets

Property from a Prominent Private Collection

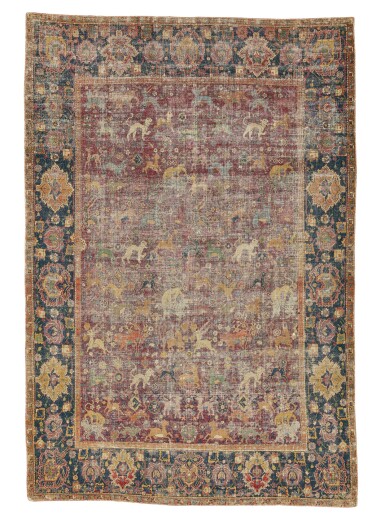

An Isphahan 'Animal' rug, Central Persia, early 17th century

Auction Closed

March 31, 12:40 PM GMT

Estimate

25,000 - 40,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

approximately 239 by 165cm.

The Vitall and Leopold Benguiat Private Collection of Rare of Old Rugs, American Art Association, New York, December 5, 1925, lot 62

Pennsylvania Private Collection, Skinner Galleries, Bolton, MA, June 3, 1986, lot 105

Property of a Southwestern Collector, Sotheby's New York, December 11, 1991, lot 56

Christie's New York, December 16, 1999, lot 209

Hali 32, October-November, 1986, p.80

Hali 61, February 1992, p.166

Hali 156, March-April 2000, p.209

This rug gives us an important insight into a transitional moment in Persian rug weaving, between the rugs of 16th century Kashan, and the 17th century production of rugs under Shah Abbas and his descendants, attributed to Isphahan. The rug offered here belongs to an extremely rare group of early 17th century rugs which both depict animals and are attributable to the city of Isphahan. In fact, the apparently only other published similar example is an animal rug formerly in the collection of John D Rockefeller and now in the Carpet Museum Teheran (see Pope, Arthur Upham, A Survey of Persian Art, London and New York,1939, pl.182 and Gans-Ruedin, E., Iranian Carpets, London, 1978, p.89), which depicts animals arranged longitudinally. The precedent of the depiction of animals in Persian weaving is firmly established by the numerous Safavid carpets of the 16th century where various forms and animals and fantastic beasts comprise a significant design element, In the majority of these 16th century carpets the animals either appear in an overall medallion design, or in the case of non-medallion carpets, co-exist harmoniously with a palmette and floral vinery lattice. The closest antecedent for the animal design of the present rug is found in the small group of 16th century Kashan animal rugs such as the Altman rug, (see Dimand, M.S. and Mailey, Jean, Oriental Rugs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1973, p. 142 , fig. 179, Inv.no.14.40.721 (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/446642) and the Peytal rug (see Beattie, May, Carpets of Central Persia, 1976, cat. No. 5, pl.3). In the 16th century silk Kashan group, and also in the rug offered here, the field is dominated by combatant and singular animals on a floral background. Salient differences in both design and structure separate the present rug from the silk Kashan animal group. In the present rug, the lateral repeat of the design is more obvious than in the 16th century Kashan rugs, making this rug appear more symmetrical. There is also a different treatment of the secondary floral motifs in the present rug from the silk Kashan animal rugs. In the two cited silk Kashans, the floral motifs are represented as individual flowering shrubs and branches along with stylized rock formations. In the present rug, and to a greater degree in the Rockefeller/Teheran animal rug, the secondary floral motifs are present as an overall flowering trellis.

These differences in the background floral representation support an Isphahan attribution for the rug offered here. The more symmetrical overall floral lattice seen in the present rug is reminiscent of the fully developed palmette and floral vinery designs found in numerous Isphahan carpets produced throughout the 17th century. (The ‘spiral vine’ or ‘in-and-out palmette’ carpets.) Furthermore, the palmette and floral vine border of the present rug is typical of these Isphahan floral carpets.The use of animals as major design motifs subsided in later 17th century Isphahan production. Perhaps this change in design impetus indicates that the present rug is a transitional piece in the development of a new Shah Abbas aesthetic at the court looms of Isphahan. It is now generally thought that the animal motifs in these carpets were deployed as individual cartoons, which the weavers were able to ‘mix-and-match’ giving the craftsman a level of artistic freedom. However, as a process this is unsuited to more commercial production, and as noted for the previous lot, by the early 17th century the ‘spiral vine’ type Isphahans were being produced in quantity for export. It is very possible only a tiny number of these transitional pieces were produced, before the weavers turned their attention to weaving the large furnishing carpets with their symmetrically disposed palmettes and repeating designs.

It is also interesting to note the similarities and differences between the present rug and the Mughal Indian animal carpets being woven during the same period (for a Mughal animal example, see Carpets from the J Paul Getty Museum, Sotheby’s New York, December 8, 1990, lot 1). The Mughal examples, excepting the strictly pictorial pieces, tend to have a more developed floral lattice with animals of fully extended gait more closely related to the drawing and design of the Rothschild/Teheran animal rug. The animals in the present rug are text-book examples of the Persian depiction of animals with a tensed, arched stance.

Despite the corroded red field, this rug remains a beautiful example of an important rug illustrating the development of Safavid Persian production. This rug’s significance as a weaving is highlighted by its inclusion in two of the great carpet collections formed in America during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, those of Henry Gurdon Marquand and of the Benguiat brothers.