Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite and British Impressionist Art

Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite and British Impressionist Art

Property from a Private Collection

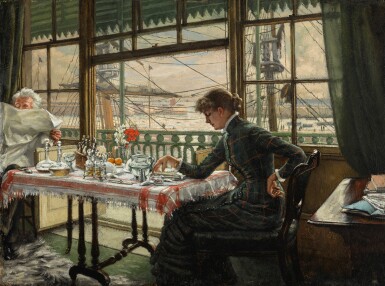

JAMES-JACQUES-JOSEPH TISSOT | Room Overlooking the Harbour

Auction Closed

July 11, 02:12 PM GMT

Estimate

400,000 - 600,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

Property from a Private Collection

JAMES-JACQUES-JOSEPH TISSOT

Room Overlooking the Harbour

signed l.r.; JTissot

oil on panel

25 by 33cm., 10 by 13in.

Robert Skinner Esq. by 1933 and thence by descent to the present owners

James Laver, Vulgar Society – The Romantic Career of James Tissot, 1936, illustrated plate XXVII;

Michael Justin Wentworth, James Tissot – Catalogue Raisonee of his Prints, 1978, pp.106, 108, illustrated fig.22b;

Michael Wentworth, James Tissot, 1984, p.131;

Christopher Wood, The Life and Work of Jacques Joseph Tissot 1836-1902, London, 1985, pp.88-89, illustrated plate 82 p.89;

Krystyna Matyjaszkiewicz, James Tissot, 1984, p.79, illustrated plate 21 p.59;

Russell Ash, James Tissot, 1995, not paginated

London, The Leicester Galleries, In the Seventies. Exhibition of Paintings by James Tissot, 1933, no.II;

The Arts Council of Great Britain, Paintings Drawings and Etchings by James Tissot 1836-1902, 1955, no.30;

Sheffield, Graves Art Gallery, Paintings Drawings and Etchings by James Tissot 1836-1902, 1955, no.41;

London, Barbican Art Gallery, James Tissot, 1984, no.77;

Paris, Musee du Petit Palais, James Tissot, 1985, no.71;

Isetan Museum of Art, Daimaru Museum in Osaka, Mie Prefectural Museum, Tochigi Prefectural Museum and Yokohama Takashimaya Gallery, James Tissot, 1988, no.34

‘Room Overlooking the Harbour… is perhaps one of the most beautiful and subtle of all Tissot’s narrative pictures of this period. Here, surely, it is not too romantic to suggest that Mrs Newton inspired Tissot to produce some of the finest of his English pictures. The delicate nuances and subtle suggestiveness of these pictures are even more successful than the earlier shipboard romances.’ (Christopher Wood, The Life and Work of Jacques Joseph Tissot 1836-1902, London, 1985, p.88)

On a warm summer’s day in the dining-room of a seaside hotel, a young woman sits reading and enjoying the cooling ocean breeze through the open window. The table is laid for a light luncheon but neither she or her elderly companion seem interested in eating, engrossed as they are in their book and newspaper. She is demurely-dressed in green tartan, buttoned high at the neck and long to the ankles and wrists, where the austerity is relieved by a modest white frill. Her hair is neatly tied-back and unadorned and she has no visible jewellery other than a simple gold bracelet. The decanters of wine are far across the table from her and she seems only interested in her literature, which is undoubtedly temperate and improving. All the signs are that she is a respectable young lady, chaperoned by her father on their vacation to the seaside. The reputation of the beautiful model who posed for Room Overlooking the Harbour was not as untarnished.

The figure of the woman in Room Overlooking the Harbour was based upon a watercolour of a woman playing chess (Museé Magnin, Dijon) which was among Tissot’s first depictions of the great love of his life, Kathleen Newton, whose story has been shrouded in mystery. Kathleen Irene Ashburnham "Kate" Kelly was born in 1854 in India, to Irish parents – her father was an army officer employed by the East India Company who retired to London with his family in the 1860s. When she was sixteen Kathleen’s father arranged for her to be married to Isaac Newton, a surgeon in the Indian Civil Service and she was dispatched to India. On the voyage Kathleen endured the unwanted attention of another traveller, Captain Palliser, who attempted to seduce her. She thwarted his advances but succumbed upon their arrival at their destination in Agra. In January 1870 she was married to Newton but on their wedding night, after consulting a priest, she confessed her liaison with Palliser to her new husband who promptly instructed divorce proceedings and sent her back to London. Her passage home was paid by Palliser in return for her promise to become his mistress but when she fell pregnant she refused to marry him. On 20 December 1871 she gave birth to an illegitimate daughter, on the same day that her decree nisi was delivered to her, dealing a double blow to her reputation. She moved in with her sister in St John’s Wood and it is said that she met Tissot, who lived nearby, when out posting a letter one day, probably in 1875. Jacques Tissot had moved to St John’s Wood following his involvement in the Paris Commune of 1871, changed his name to James Tissot and established a flourishing career as a painter of elegant contemporary life. From the moment he saw Kathleen he was besotted with her but as an Irish Catholic divorcée she would have been considered déclassé in Victorian society and therefore he could not marry her. She moved into Tissot’s beautiful home at 17 Grove End Road and in 1876 her son Cyril was born – it is likely that Tissot was his father. Although it was common for artists of this period to have mistresses, Tissot was unusual in that he openly lived with Kathleen and painted her repeatedly in domestic settings rather than the high-society scenes of his earlier period. Invitations ceased to arrive at 17 Grove End Road and people crossed the road to avoid him, as ‘Society’ turned its back on the artist and his live-in mistress with her illegitimate children. She began to recede into the shadows of Tissot’s house, kept indoors or in the leafy garden, away from prying eyes and whispers of impropriety. However, far from disappearing entirely, her face appeared in virtually every picture of this period from the glamorously simple Mavourneen of 1877 (an oil and an engraving) and July of 1878 to the more narrative The Warrior’s Daughter of 1878 and A Passing Storm (Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Canada).

Tissot’s paintings of Kathleen, taking tea in riverside taverns, picnicking in summer gardens or enjoying fete days, suggest an untroubled romantic idyll but the love-affair had a dramatic and tragic end. Kathleen became ill, probably with tuberculosis, and in 1882 when she was twenty-eight she took her own life, apparently to save Tissot from the agony of seeing her decline. He was devastated, spending four days sitting beside her coffin and abandoning London for Paris on the day after her funeral because he could no longer endure the emptiness of his home. The gossips in London stopped whispering about Kathleen and in Paris few would have known of Tissot’s lost-love. In one last tragedy, Kathleen was forgotten. The woman in Tissot’s London paintings was simply referred to as la mystérieuse for over half a century until her niece, Lillian Hervey, though just 7 years of age at the time of her aunt’s passing, came forward with memoirs in 1971.

The setting of Room Overlooking the Harbour was probably from the first-floor seafront rooms of the Castle Hotel at Goldsmid Place (now Harbour Parade) in Ramsgate. Ramsgate was one of the fashionable south-coast seaside resorts in the late nineteenth century, within easy reach of London. In 1876 Tissot made the same room the subject of several pictures, including a pen and ink study Ramsgate (Tate), a dry-point of the same title (example sold in these rooms, 17 December 2015, lot 228) and the painting A Passing Storm (Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Canada). Tissot’s interest in depicting figures in interiors with windows opening onto riverside or seaside vistas has often been cited as an influence from his friend J.A.M. Whistler’s etchings of 1871 entitled The Thames Set, which were views of boats and taverns at Wapping in London. Whistler and Tissot met in Paris in around 1856, while he was enrolling on a training course to equip him to enter the prestigious Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Both artists drew heavily on ukiyo-e Japanese prints in their compositions, with ‘processional’ grouping of figures strung from one side of the composition to the other across the surface of the picture with a distant view behind. Tissot began his own depictions of women and young men in Thames-side taverns in the early 1870s with pictures like Bad News of 1872, An Interesting Story of c.1872 and The Tedious Story of c.1872 – all of which were painted in Wapping and Greenwich. The 1872 pictures were mainly set in late eighteenth-century dress and the contemporary costumes in pictures like Room Overlooking the Harbour is more convincing - perhaps because the artist was now inspired by a beloved muse whose every-day activities he wanted to capture forever in his paintings.

Room Overlooking the Harbour was included in an important exhibition of Tissot’s work held at the Leicester Galleries in 1933 In the Seventies. Exhibition of Paintings by James Tissot. At this time Mrs Newton’s name was not recalled and almost nothing was known of the woman who gazed out from many of the exquisite pictures in the show. However, a man in his late fifties walked up to one of the paintings (perhaps the present picture) and exclaimed “That was my mother”, before turning and leaving – it is thought that this was Cecil Ashburnham, son of Kathleen and Tissot. The proprietors of the gallery followed him to ask his name, but he was lost in the crowd and Kathleen’s identity as la mystérieuse endured for another four decades.