European Art: Paintings & Sculpture

European Art: Paintings & Sculpture

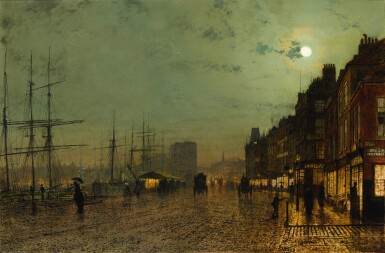

JOHN ATKINSON GRIMSHAW | GLASGOW DOCKS

Lot Closed

June 18, 01:24 PM GMT

Estimate

200,000 - 300,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

JOHN ATKINSON GRIMSHAW

1836 - 1893

GLASGOW DOCKS

signed and dated l.r.:Atkinson Grimshaw/ 1886+

oil on canvas

24 by 36in., 61 by 91cm.

Please note: Condition 11 of the Conditions of Business for Buyers (Online Only) is not applicable to this lot.

To view Shipping Calculator, please click here

Christie's, London, 12 June 2001, lot 55, where purchased by a private collector in Ireland

'They are remarkable in that they record the contemporary port's role within Victorian life; they appealed directly to Victorian pride and energy. They also show that same darkness, a mysterious lack of complete experience of the subject which one associates with large cities and big business, which Dickens recounts so well in Bleak House and Great Expectations and for which Grimshaw's moonlight became a perfect metaphor.'

David Bromfield, Atkinson Grimshaw 1836-1893, exhibition catalogue, 1979-1980, p.15

The growth of the industrial cities of Britain were a source of great inspiration for John Atkinson Grimshaw, whether he was painting the suburban villas of the Leeds' factory and mill owners or the shopping streets and docks of Liverpool, Whitby and Glasgow. Grimshaw celebrated the age of industry, commerce and conspicuous wealth in a series of paintings in which moonlight and lamplight contrast with one another and skeletal trees or ship's rigging are interchangeable. Often there is a suggestion of social division; of a servant girl making her way home through puddled streets before the imposing facade of her master's home, or a homeward-bound farmer wending through a suburban street. In the present picture of the Broomielaw Quay on the Clyde in Glasgow, Grimshaw made the social contrast particularly apparent with affluent and elegantly-dressed pedestrians alongside road-menders and the merchant ships of the working class city. The figures are silhouetted against the golden light radiating from the tantalising shop windows including Allsops Wine Merchants where an array of bottles have tempted a young man in whilst a woman walks by her attention distracted by a newspaper-boy selling the evening edition. It is a typical Victorian street scene with carriages passing through the heavy city fog and rain but Grimshaw transformed what would have been a dark and damp street into a richly atmospheric cityscape. The large black carriages emerge from the gloom of the city with their lights appearing like small beacons glinting through a sea mist. On the left, the rigging of the ships is finely detailed and meticulously depicted as the masts tower above those below, equaling the height of the facing buildings. The shopfront spills its yellow light onto the pavement, making the wet stone slabs glow beneath the feet of the passers-by – resembling a street paved with gold.

Grimshaw is well known for his dockside scenes which became a reccurring theme in his work from around 1875 when he became established on the London art market. His growing popularity in the 1880s, particularly with art collectors in the northern urban centres, encouraged him to paint the industrial ports and harbours of Liverpool, Hull, Scarborough, Whitby and Glasgow. A new generation of wealthy industrialists, possessed of great civic pride, provided Grimshaw with a plethora of clients. The art dealer Thomas Agnew's archives reveal the artist's work recurring frequently in their stockbooks of the period, probably selling through their galleries in Manchester and Liverpool or through their considerable connections in Glasgow. In the 1870s and 1880s Grimshaw was under considerable financial pressure when he was called upon to honour a loan he had guaranteed for an untrustworthy friend which resulted in Grimshaw losing his house in Scarborough and his servants werev dismissed. He returned to his previous residence Knostrop Hall in Leeds, later hiring a studio in London which he used until 1887. This sudden downturn in his finances led to a dramatic increase in the artist's production and coincides with the first moonlit urban and dockside scenes. Men made wealthy by trade were keen to own his lively scenes of city life depicting the ports that were the lifelines of an empire in its heyday. The Broomielaw Quay had been the harbour of Glasgow since the end of the seventeenth century and was named after the Brumelaw Croft, a stretch of land between Anderson Quay and Victorian Bridge. Following remodelling by Thomas Telford Broomielaw became a busy dock. In 1870 Glasgow produced more than half of Britain's shipping tonnage and a quarter of all locomotives worldwide. By the end of the Nineteenth Century it had become known as the "Second City of the Empire", its shipping industry supporting and linking Britain's vast areas of jurisdiction throughout the globe. This time of growth and prosperity led to the building of Loch Katrine, opened by Queen Victoria in 1859 to supply the city with water, and later the subway, opened in 1896. An ambitious rejuvenation plan was also underway including the building of an impressive City Chambers by William Young and Glasgow University's main buildings by the great Sir George Gilbert Scott. Broomielaw was also the place that many Glaswegians left for their holidays with passengers alighting from the world famous Henry Bell's Comet, the first commercial steam ferry. The Clutha Ferries ran a half hourly service between Victoria Bridge and Whiteinch stopping at the Broomielaw Quay on their journey. The ferries brought passengers from the various neighbouring shipyards and docks and operated until 1903; the opening of the subway underground in 1896 and the introduction of the tram system in 1901 saw the demise of the ferry system.

Grimshaw deliberately avoided making obvious social commentaries in his work. His pictures are a truthful snapshot of contemporary life, albeit with a few architectural liberties for picturesque effect. To emphasise the poverty and hardship that was a feature of every Victorian city would have been unpopular with his affluent clients. By avoiding sentimentality and dour representations of the working poor, Grimshaw allows us to enjoy his beautiful pictures. Using moonlight and the warmth of the gas lamps to illuminate this scene of everyday life Grimshaw transformed the familiar; the half-light giving the working dockside and its figures an ambiguity that is delightfully intriguing.