Tableaux et Dessins 1400-1900 incluant des œuvres d’une importante collection privée symboliste

Tableaux et Dessins 1400-1900 incluant des œuvres d’une importante collection privée symboliste

Henri-Joseph Harpignies

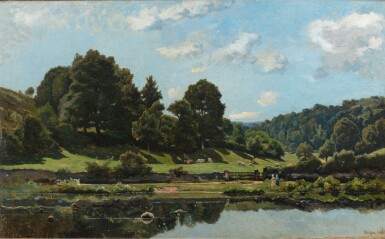

A Meadow in the Bourbonnais: Morning

Estimate

30,000 - 50,000 EUR

We may charge or debit your saved payment method subject to the terms set out in our Conditions of Business for Buyers.

Read more.Lot Details

Description

Henri-Joseph Harpignies

Valenciennes 1819 - 1916 Saint-Privé

A Meadow in the Bourbonnais: Morning

Oil on canvas

Signed and dated lower left h harpignies 1876 and inscribed lower right (barely legible)

50 x 80,5 cm ; 19¾ by 31¾ in.

Acquired directly from the artist, in 1877;

Thence by descent to the present owner.

Unpublished and in the same private collection since it was bought direct from the painter, this wonderful signed sketch, very finished, was made in preparation for one of the artist’s most well-known paintings, now in the USA: A meadow in the Bourbonnais, morning (111.8 x 167.6 cm; Brooklyn Museum, inv. 55.18 ; ill. 1).

Originally destined for a career in his father’s business enterprises, Henri Joseph Harpignies turned definitively to painting in 1846. Trained by Achard, he travelled in France, Holland, Flanders and Italy and was strongly influenced by his successive encounters with Corot and Boudin.

Although the Forêt de Fontainebleau was one of his favourite subjects from the mid-1850s onwards, he settled in the Allier at the beginning of the following decade, first in Hérisson, in whose surroundings he painted this view, and then in Saint-Privé.

The large painting now in Brooklyn, exhibited at the Salon in 1876, was executed in his studio, but the present sketch was painted from nature, en plein-air, as Harpignies himself wrote in the receipt he signed for the work’s buyer, Monsieur Paul Blain, on 7 April 1877 (ill. 2). The artist was sufficiently proud of the painting, which has a rapid but confident brushstroke, to sign it twice, indicating that he saw it as a finished work rather than a simple preparatory study. A letter from Frantz to Blain (ill. 3) expressing the same esteem and advising him to buy the work, cites Harpignies’s own preference for this canvas over the final painting:

‘I took myself to Rue de Furstemberg to see my friend Harpigny (sic) and here is the outcome of my visit. I found an excellent painting 0.80 wide and 0.50 high, in a flat frame. This canvas was painted from nature and depicts the subject of the painting shown in the last Salon (see in this regard the article by Cherbullier (sic) in last year’s Revue des deux mondes).

Harpigny prefers this painting to the one that was exhibited, and in my view it is full of light and lyricism’.

While the article by Victor Cherbuliez mentioned above, which was indeed published in the 1876 edition of Revue des Deux Mondes (Revue des Deux Mondes, 3e période, vol. 15, 1876, p. 517), certainly refers to the Brooklyn painting, it is worth citing the passage in question in full, since could so easily represent the present work:

‘Rational and judicious Impressionism has had a number of grand entrances at the Salon; this year it has made a brilliant appearance. We know of scarcely any landscape more beautiful than la Prairie du Bourbonnais by M. Harpignies. With the ingenious grandeur of its composition, the noble organization and line, the sure drawing, the almost geometrical solidity of the construction, the strict subordination of detail to mass, this meadow recalls Poussin; but it not a theatrical landscape, a stage prepared for important figures, for the famous protagonists of history or mythology. What would Orpheus or Diogenes do here? M. Harpignies shows us his meadow as he himself saw it one morning. There, he was apparently one of the happiest men and artists and he introduces us to his joys. This beautiful painting creates a profound and intimate impression. We can sense that the air there is fresh, it circulates everywhere and we can breathe it deep into our lungs. We can also sense that the grass is soft: lucky cows that graze it! The oak trees cast a velvety shadow over the fields; we long to sit there and pass the time gazing at the outlines of the hills that retreat so effectively into the distance and those little grey and white clouds that sail softly through a light, transparent sky. Poussin created heroic landscapes; M. Harpignies’s meadow is on a human scale; heroes would not feel at home, it is a place for cows and dreamers.’

Cherbuliez’s comments on the large painting are very useful. Firstly, they describe the scene very accurately, with its atmospheric qualities and the natural impression that permeates the whole. But above all, they position Harpignies among the ‘rational and judicious’ Impressionists. While this expression, invented by the author, can accurately be applied to the final painting, by extension it can also be applied to the present work, painted en plein-air, sur le motif, and truly Impressionist.

This is the great power of this work: it fearlessly rivals Impressionism in terms of its method (en plein air); its genuine and spontaneous view of nature; and its observation of light effects on a landscape. Harpignies here demonstrates a very modern approach that makes him the equal of his contemporaries.

You May Also Like