Auctions

Buy Now

Collectibles & More

Books & Manuscripts

Fine Manuscript and Printed Americana

Fine Manuscript and Printed Americana

Auction Closed

January 27, 09:56 PM GMT

Estimate

20,000 - 30,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

WASHINGTON, GEORGE

AUTOGRAPH MANUSCRIPT FRAGMENT FROM HIS UNDELIVERED FIRST INAUGURAL ADDRESS

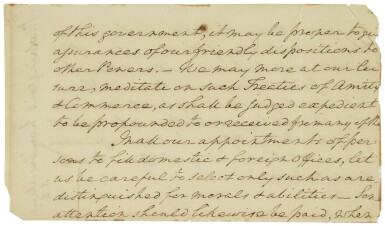

On a slip of laid paper (4 x 7 in.; 102 x 178 mm) cut from a larger sheet, evidently the upper portion of original pages 45–46, containing approximately 138 words in Washington's holograph, [Mount Vernon, January 1789], right margin of verso docketed by Jared Sparks "Washington's handwriting"; some very minor marginal chipping and repair, one corner broken (bearing portions of four letter) but present.

"We should seek to find the Men who are best qualified to fill Offices: but never give our consent to the creation of Offices to accomodate men": an important fragment from Washington's discarded first inaugural address.

The former President of the Constitutional Convention strongly endorses the new nation’s constitutional, representative government: “this Constitution, is really in its formulation a government of the people; that is to say, a government in which all power is derived from, and at stated periods reverts to them.” Although George Washington did not receive official notification of his unanimous election to the presidency until 14 April 1789, his elevation to that office was essentially a foregone conclusion from the time that New Hampshire's ratification of the United States Constitution, 21 June 1788, provided the ninth-state approval necessary to put the new governmental compact into effect. Washington's ambivalence about becoming the chief executive is well known: on 1 April 1789 he famously wrote to Henry Knox, Acting Secretary of War and his old comrade in arms, that "my movements to the chair of Government will be accompanied with feelings not unlike those of a culprit who is going to the place of his execution: so unwilling am I, in the evening of a life nearly consumed in public cares, to quit a peaceful abode for an Ocean of difficulties, without that competency of political skill—abilities & inclination which is necessary to manage the helm" (sold, Sotheby's, 1 November 1993, lot 232).

Washington's modesty—false or not—was belied by his willingness to serve. Indeed, the very office of presidency, as constituted, owes much to the character of Washington. His fame as the steady hero of the Revolution, his manifest lack of personal ambition, and his determination not to profit from public service won him a reputation unapproached by any other American of his—or any subsequent—day. Despite his strong desire to live in the "peaceful abode" of his Mount Vernon estate, he felt compelled to give active support to the federal cause, agreeing to serve as president of the Constitutional Convention. Even before the delegates gathered in Philadelphia, there was a widespread belief that however the office of chief executive was ultimately defined, Washington was its only possible candidate. The potentially dictatorial powers invested in the presidency of commander in chief of the armed forces could only have been approved under the near-universal assumption that Washington would be that trustworthy commander.

Washington accepted the inevitability of his election, and as early as January 1789 he had begun work on an Inaugural Address. With the assistance of David Humphreys, Washington wrote a lengthy and thoughtful charge to Congress, touching on a myriad of issues and recommendations: implementation and amendment of the Constitution, proposed legislation, organization of the judicial branch, taxation, defense, and encouragement of national commerce and culture. In February, Washington sent the text of the address to James Madison for his review and comment. While Madison's response does not survive, it can be assumed that he counseled Washington to deliver a less detailed, less radical, and—if only for practical reasons—shorter speech to Congress and his fellow citizens. Washington complied, and his first Inaugural Address was set aside in favor of a briefer, more personal statement, probably drafted with the help of Madison. It was this shortened and somewhat sterilized version of Washington's vision for the country that he read at his inauguration at Federal Hall, New York, 30 April 1789.

Washington's original Inaugural Address survived in holograph among his papers at Mount Vernon until the later 1820s, when it was transferred—with eight crates of other original documents—to the custody of Bostonian Jared Sparks, the nineteenth-century "editor" of Washington's writings. In consultation with Madison, Sparks decided that the undelivered Address should not be included in his selection of Washington's works. Having determined that the 73-page manuscript was now superfluous to him, Sparks made the much more startling decision to distribute the address to the autograph hunters and other souvenir hounds who had begun to hector him for examples of Washington's signature. Content at first to scatter the address leaf by leaf, Sparks eventually took to cutting individual leaves to into several smaller slips, evidently so he could accommodate more requests. James Thomas Flexner's excoriation of Sparks's "most horrendous historical vandalism" scarcely seems condemnation harsh enough.

Largely through the efforts of a new breed of manuscript collector—notably Forest G. Sweet and Nathaniel E. Stein (from whose collection this fragment derives)—Washington's first Inaugural Address was recognized and, in part, rescued. The recto of the present portion of the address concludes Washington's thoughts on treaties with other governments and begins a consideration of how best to fill all of the offices of the new government:

"of this government, it may be proper to give assurances of our friendly dispositions to other Powers. We may more at our leisure, meditate on such Treaties of Amity & Commerce, as shall be judged expedient to be propounded to or received from any of the[m].

"In all our appointments of persons to fill domestic & foreign offices, let us be careful to select only such as are distinguished for morals & abilities—Som[e] attention should likewise be paid, when"

The verso continues on the subject of finding appropriate office holders, albeit with some interruption due to the lower portion of the original leaf being missing: "It appears to me, that it would be a favorable circumstance, if the characters of Candidates could be known, without their having a pretext for coming forward themselves with personal applications. We should seek to find the Men who are best qualified to fill Offices: but never give our consent to the creation of Offices to accomodate men[.]"

LITERATURE:

cf. The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, ed. Abbot & Twohig, 2:152–77; Nathaniel E. Stein, "Washington's Discarded Inaugural Address," in Manuscripts, vol. 10, no. 2 (Spring 1958): 2–17

PROVENANCE:

Bushrod Washington — Jared Sparks — Forest G. Sweet (Parke-Bernet, 8 May 1957, lot 370 [part]) — Nathaniel E. Stein (Sotheby Parke Bernet, 30 November 1979, lot 186)