Arts of the Islamic World & India

Arts of the Islamic World & India

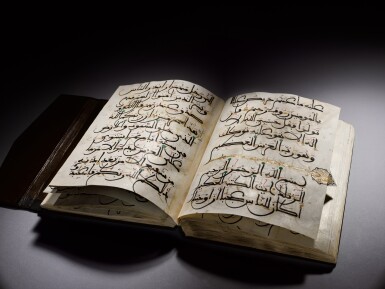

A large illuminated volume from an eight-volume Qur'an in Maghribi script on paper, Spain or North Africa, 15th century

Estimate

150,000 - 250,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

Arabic manuscript on watermarked paper, 109 leaves, plus 2 fly leaves, 9 lines to the page written in Maghribi script in black ink, diacritics in yellow, green, blue and red, verses separated by triangular clusters of 3 gold roundels, 'ashr marked by gold and polychrome medallions, hizb marked by marginal gold medallions, surah headings in gold Kufic flanked by marginal roundels with arabesques, in European dark brown leather binding with flap

31.4 by 23.4cm.

Ex-private collection, France, early 20th century

This impressive volume was part of an eight-volume Qur’an, three volumes of which are in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (inv. nos.Arabe 438, Arabe 439 and Arabe 440). Volume II of the manuscript (inv. no.Arabe 439) bears an inscription on the opening flyleaf stating that the manuscript was taken by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (1500-58) himself, during his expeditions in Tunis and Algiers and placed in the Escorial library. The volumes migrated to France via Cardinal de Granvelle (1517-86) who acquired them for his own collection.

Arabic manuscripts, particularly Qur’ans and prayer books, came into European collections in the sixteenth century primarily as spoils of war. While this could lead to the destruction of such works, numerous examples were saved as trophies and merchandise, and others preserved by distinguished patrons of Arabic texts (see Jones 1987 for a further discussion on the various contexts in which Arabic manuscripts entered European collections in Renaissance Europe).

In 1535, Charles V assembled a large army in order to sack and conquer Tunis, wrestling the city away from Ottoman rule. During this siege, Charles V and his forces looted manuscripts from the city, including a Mamluk volume of Bukhari’s Sahih, now in the Vatican library, a Qur’an produced in Seville, dated 1227 AD, now in the Bavarian State Library (Seidensticker 2017, p. 79), and the multi-volume Qur’an from which the present lot originates mentioned above.

In his entry on the BNF volumes, Déroche expands on their provenance. The inscription on the fly leaf of volume II records that the manuscript was removed from the Escorial library by Cardinal de Granvelle who took it for his own collection, at which point they must have entered France. The manuscript was subsequently in the Séguier-Coislin library, assembled by Chancellor Séguier (1635-72) as evidenced by note made during an appraisal of his collection dated 1672. Finally, it was bequeathed in 1732 to the abbey of Saint-Germain des Près (Déroche 1983-85, pp.37-38). It is highly unlikely that Charles V, along with the subsequent illustrious owners, would have taken only select volumes from this eight-volume Qur’an into their collection. The present volume was therefore almost certainly acquired by Charles V in Tunis and remained with the other volumes as they entered France before they became dispersed into various collections, the present volume entering a private collection by the early twentieth century.

This manuscript is not only remarkable for its provenance, but also as a magnificent copy of the Qur’an in its own right. It is copied in a large and bold Maghribi script, reminiscent of the renowned pink Qur’an of the late twelfth and early thirteenth century. The terminal mims swoop below and intersect the line of text beneath creating a dynamic lattice of strokes across the page. Notably, like the BNF volumes, the Qur’an is written on watermarked paper, and bears two watermarks. The first is in the shape of a crescent surmounted by a cross, as recorded on the paper stock of the BNF volumes, and the other comprises a crown within a circle. The use of two stocks of paper reflects the costly endeavour of the commission which must have been completed over a considerable length of time. For a further fourteenth/fifteenth century Maghribi Qur’an volume on watermarked paper, see Islamic Calligraphy, 2003, pp.72-73, no.32).

You May Also Like