Books and Manuscripts: A Summer Miscellany

Books and Manuscripts: A Summer Miscellany

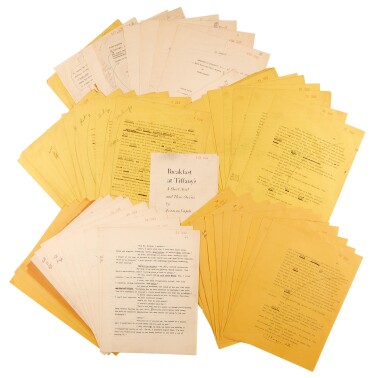

CAPOTE | Breakfast at Tiffany's, revised typescript, 1958

Lot Closed

August 4, 02:12 PM GMT

Estimate

120,000 - 180,000 GBP

Lot Details

Description

CAPOTE, TRUMAN

BREAKFAST AT TIFFANY'S, REVISED TYPESCRIPT

the setting copy with copious autograph revisions throughout in pencil, every page containing annotations, comprising revisions, meticulously erased deletions, and other substantive changes (the protagonist's name changed from "Connie Gustafson" to "Holly Golightly" throughout), as well as the correction of spellings and other accidentals, also with a small number of further corrections by the copyeditor, annotated in the margins for casting off into galleys and each leaf marked off with a tick, 84 numbered pages, 4to ("letter" size, 216 x 279mm), on three paperstocks (yellow Hammermill Bond, white Strathmore Bond, and an unwatermarked paper of lower quality), with typescript preliminaries ("About the Author", title page, half-title, contents, dedication, copyright page, list of other publications) all marked up for the press (7 pages), also an ink mock-up of the cover, printer's ink stamp ("Haddon Craftsmen") with receipt date to the verso of the contents page (27 June 1958), copyright page (5 August 1958), and mock-up cover (20 August 1958), each leaf with the printer's number stamp, also with the Random House address label for return ("Mr Truman Capote | 70 Willow Street | Brooklyn 1, New York"), altogether 93 pages, 1958; nicks and tears to a few leaves (especially pp. 1, 72, 84), printer's ink marks, a small number of leaves (unwatermarked paper stock) browned and somewhat brittle

"...It was a warm evening, nearly summer, and she wore a slim cool black dress, black sandals, a pearl choker. For all her chic thinness, she had an almost breakfast-cereal air of [rude - deleted] health, a soap and lemon cleanness, a rough pink darkening in the cheeks. Her mouth was large, her nose upturned. A pair of dark glasses blotted out her eyes. It was a face beyond childhood, yet this side of belonging to a woman. I thought her anywhere between sixteen and thirty; as it turned out, she was shy two months of [a - revised to: her] nineteenth birthday..." (The narrator's first sight of Holly Golightly)

CAPOTE'S FINAL WORKING TYPESCRIPT OF HIS MOST FAMOUS STORY, providing extensive and detailed insight into the working method of a writer described by Norman Mailer, when reviewing Breakfast at Tiffany's, as "the most perfect writer of my generation, he writes the best sentences word for word, rhythm upon rhythm". This draft shows Capote finessing his inimitable style, which he himself placed at the centre of his art: "Essentially I think of myself as a stylist and stylists can become notoriously obsessed with the placing of a comma, the weight of a semi-colon. Obsessions of this sort, and the time I take over them, irritate me beyond endurance." (interview with Pati Hill, Paris Review, 1957).

These revisions show exactly the obsession over detail that both frustrated Capote (after all, what author would not prefer to be the genius whose words flowed with immediate perfection) but were also key to his success as a writer. Many of the revisions in this typescript modulate the vocabulary - "mad" to "vexed", "touch" to stroke", and dozens of other such changed - or excise unnecessary words. Capote himself later reflected that Breakfast at Tiffany's marked a turning point in his style towards "a pruning and thinning-out to a more subdued, clearer prose." (interview with Roy Newquist, Counterpoint, 1964). A characteristic example of how Capote revised his text towards a leaner prose comes when Holly reminisces about her brother Fred, with his slow mind and prodigious appetite for peanut butter. Where Capote had originally typed "Poor Fred, I'm surprised they took him in the army. Have you got anything to eat? I'm starving." This is improved with a handwritten revision to: "Poor Fred. I wonder if the army's generous with their peanut butter. Which reminds me, I'm starving."

The character of Holly Golightly is of course the heart of Breakfast at Tiffany's, and the most striking change made by Capote in this draft relates to her. Capote's most enduring fictional creation, a charmingly contrarian free spirit in a little black dress (perhaps, indeed, the little black dress), Holly Golightly has bewitched and inspired for more than sixty years, but the character only reached her completed form in this final draft. The guitar-playing socialite who lives by her charms, is never seen without her dark glasses, spends her Thursdays visiting a gangster in Sing Sing, is described admiringly as a "real phony", and suffers from the "mean reds", was, until Capote took up his pencil for the final time, named Connie Gustafson. Whilst Connie Gustafson may be more plausible as a child bride from Tulip, Texas, she would never have had the impact on the world that she has had as Holly Golightly. Undoubtedly one of the great names of modern comedy, it is as magnificently implausible as its owner and connects to her character in a number of ways: "Golightly" reflects the lightness with which she treats the world, her lack of attachment to place, and perhaps hints at promiscuity; whilst "Holly" will prickle if you get too close.

Some of Capote's final revisions also temper the sexual content of the story, although of course it remains far more explicit than the 1961 film. Holly's memorable account of the "mean reds" originally included the admission that "Boy, I have hit the hay with some real ghastlies just because I couldn't stand it any longer. I had to have somebody hold me." Another - and more outrageous - example comes in a later conversation between Holly and her man-hunting flatmate Mag Wildwood, in which the latter admits that during sex she pictures the statue of her forefather "Papadaddy Wildwood" in his military uniform that stands in her hometown. This exchange is deleted in its entirety.

This typescript was the final stage in a long and complex history of composition. Capote described in a 1957 interview with Pati Hill that he would write his first drafts in longhand, "Then I type a third draft on yellow paper, a very special certain kind of yellow paper ... when the yellow draft is finished, I put the manuscript away for a while, a week, a month, sometimes longer. When I take it out again, I read it as coldly as possible, then read it aloud to a friend or two, and decide what changes I want to make and whether or not I want to publish it. I've thrown away rather a few short stories, an entire novel, and half of another. But if all goes well, I type the final version on white paper and that's that." He always prefered to compose in pencil, and did most of his writing in bed, the typewriter on his knees. This rigorous sequence of drafts evidently demanded more self-discipline than Capote was able to bring to his work: this typescript, although predominantly on yellow paper, is the final "white paper" version sent to the publisher, and he continued to tinker creatively with his text until the last possible moment. In the same Paris Review interview Capote himself admitted the pleasures and importance of such revisions: "in the working-out, the writing-out, infinite surprises happen. Thank God, because surprises, the twist, the phrase that comes at the right moment out of nowhere, is the unexpected dividend, that joyful little push that keeps a writer going."

This typescript was submitted to Random House, who published all of Capote's major works, in May 1958, just before Capote departed for a sojourn in Greece. Breakfast at Tiffany's had been sold to Harper's Bazaar for their July 1958 issue but a change of editorial personnel led to worry about the sexual content of the story, and the possibility of offending Tiffany's, led to a last-minute cancellation. An offended Capote ("...Publish with them again? Why I wouldn't spit on their street...") quickly sold the story to Esquire, but by the time it appeared in the November issue Random House had already published the novella in book form, bolstered with the inclusion of three short stories. Unusually, therefore, periodical publication came after its appearance in book form and the Esquire text will almost certainly have been derived from Random House proofs derived from the current typescript.

Breakfast at Tiffany's was an immediate success, both critically and commercially. The 1961 film that followed took much out of Capote's text - references to homosexuality, Holly's arrest, not to mention horseriding in Central Park - and introduced much else - 'Moon River', Audrey Hebpurn's Givenchy dresses, and the inevitable Hollywood ending - but it retained more of the spirit of the original than is often acknowledged. Capote himself was highly critical of the film but when he described his aim in Breakfast at Tiffany's he reaches what unites both versions of the story:

"The main reason I wrote about Holly, outside of the fact that I liked her so much, was that she was such a symbol of all these girls who come to New York and spin in the sun for a moment like May flies and then disappear. I wanted to rescue one girl from that anonymity and preserve her for prosperity."

Few, if any, literary manuscripts by Truman Capote of equal importance to this remain in private hands. His archive is divided between the New York Public Library and the Library of Congress (the latter of which includes another draft of Breakfast at Tiffany's). THIS IS A UNIQUE OPPORTUNITY TO ACQUIRE A MAJOR LITERARY MANUSCRIPT AND THE ORIGIN OF HOLLY GOLIGHTLY, A UNIQUELY FASCINATING AND ENDURING CHARACTER.

PROVENANCE:

RR Auctions, 25 April 2013, lot 283

To view Shipping Calculator, please click here