19th Century European Art

19th Century European Art

Property from the Collection of J.E. Safra

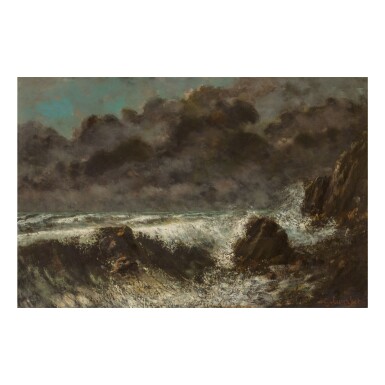

GUSTAVE COURBET | LA MER ORAGEUSE

Auction Closed

January 31, 04:23 PM GMT

Estimate

500,000 - 700,000 USD

Lot Details

Description

Property from the Collection of J.E. Safra

GUSTAVE COURBET

French

1819 - 1877

LA MER ORAGEUSE

signed G. Courbet (lower right)

oil on canvas

25½ by 38½ in.

65 by 98 cm

Galerie Bernheim Jeune, Paris

Sears Collection, Boston

E.V. Thaw, New York

Mr. and Mrs. Robert E. Benjamin, Great Neck, New York (by 1961 and sold, Christie's, London, July 3, 1973, lot 2, illustrated, as La Vague)

Sale: Sotheby's, New York, May 7, 1998, lot 146, illustrated (as The Wave)

Acquired at the above sale

Robert Fernier, La vie et l'oeuvre de Gustave Courbet, Lausanne, 1978, vol. II, p. 90, no. 707, illustrated p. 91

Pierre Courthion, L'opera completa di Courbet, Milan, 1985, p. 112, no. 680, illustrated p. 111

Pierre Courthion, Tout l'oeuvre peint de Courbet, Paris, 1987, p. 111, no. 680, illustrated

New York, New Gallery, Gustave Courbet, Landscapes and Seascapes, October 17-November 4, 1961, no. 8 (lent by Mr. and Mrs. Robert E. Benjamin)

Gustave Courbet loved the ocean, and his earliest “sea landscapes,” as he called them in his correspondence, date to 1841, when he first visited the Normandy coast. He returned to the subject in 1854 and 1857 when staying with his friend Alfred Bruyas in Montpellier and later when visiting Trouville in 1865 (fig. 1). These explorations culminated in Étretat where, from August to September 1869, the artist’s intense focus and creativity produced a group of paintings of gentle waves rolling out to sea under sunny skies — or, as in the present work, crashing violently along the shorelines under stormy skies. By the time Courbet returned to Paris, he had painted twenty seascapes, with two of the largest views destined for the Salon of 1870 (Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, ed., Letters of Gustave Courbet, Chicago, 1992, p. 354, no. 69-9). This would be the first time Courbet showed the Salon jury a seascape, and one quickly entered the Musée de Luxembourg (a museum devoted to living artists) where it received public acclaim (fig. 2). The welcome reception delighted the painter, who wrote to his parents “nobody has ever had a success like the one I had this year with my seascape” (Chu, ed., p. 336, no. 70-20). While his plein air painting in Normandy followed the example of earlier French artists (notably Eugène Delacroix) and anticipated the work of the Impressionists, with La mer orageuse (also known as La vague) Courbet created an entirely new subject. In this work, a tumultuous wave occupies the width of the canvas to confront the viewer. The series would come to represent an integral part of his oeuvre and demand the attention of audiences for well over a century (Charlotte Eyerman, “Seascapes,” Courbet and the Modern Landscape, exh. cat., J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, 2006-2007, p. 103; Dominique de Font-Réaulx, Gustave Courbet, exh. cat., The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008, p. 290).

With his marine compositions, Courbet followed a tradition of painting that included the open skies and vast horizons of seventeenth century Dutch master Jan van Goyen and the swirling sublime color and movement of Joseph Mallord William Turner’s paintings in nineteenth century Britain (fig. 3). Yet Courbet’s response to the sea was decidedly more avant-garde, and his wave series revealed an interest in water’s form and content rather than as a setting for narrative (Eyerman, p. 103-4). Painted with the same virtuosity and technique used to define the craggy rock formations of Ornans, the present work consists of a buildup of paint from brush and palette knife to convey the physicality of the subject. As they crest and roll to shore, the dark, undulating forms of the waves dominate the canvas, their shape reflected in the black clouds that fill the sky and fall to the horizon as the storm intensifies. In the darkness, irregular lines of foamy white crests extend from the distance to consume the forefront of the picture plane. Like the rocks swallowed by the water, the viewer is overtaken by the weight and power of Courbet’s subject. As such, La mer orageuse is is the type of painting championed by nineteenth century French writer and critic Émile Zola, because it rejected pictorial conventions of idealized nature. As Zola explained, when confronted by Courbet’s marine painting in the 1870 Salon, the contemporary viewer should not “expect some symbolic work in the style of Cabanel or Baudry: some naked woman…. Courbet quite simply painted a wave, a real wave…. From a technical perspective it is superb” (as quoted in de Font-Réaulx, p. 290).

Distinctive and original as Courbet’s wave series is, its genesis can be traced back to other influences. La mer orageuse may have been inspired by Courbet’s familiarity with Japanese prints, such as Hokusai’s album One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji, which had circulated in artistic circles in Paris in the 1860s, particularly the artist’s japoniste friends such as Henri Fantin-Latour and John Abbott McNeill Whistler (fig. 4, Sarah Faunce and Linda Nochlin eds., Courbet Reconsidered, New York, 1988, p. 190). At the same time, in La mer orageuse and others in the series, there is a tension between the violently rushing waters of the wave and the pictorial sense of stasis and monumentality, which may be attributed to the recent advent of photography. As with Courbet’s painting, the innovative experiments of contemporary French photographer Gustave Le Gray investigated light and its relationship to water, and allowed the fugitive moment of moving water to be fixed (fig. 5). Like Le Gray’s photography, Courbet’s Realist waves were taken from direct experience of nature, yet were also influenced by the artist’s memory and sensibility. As the Naturalist writer Guy de Maupassant observed firsthand during a visit with Courbet in Étretat, the artist’s process, from observation to creation, could be considered as agitated and tumultuous as a stormy sea:

"In a great bare room a fat, dirty, greasy man was spreading patches of white paint on a big bare canvas with a kitchen-knife. From time to time he went and pressed his face against the window pane to look at the storm. The sea came up so close that it seemed to beat right against the house, which was smothered in foam and noise. The dirty water rattled like hail against the window and streamed down the walls. On the mantelpiece was a bottle of cider and a half-empty glass. Every now and then Courbet would drink a mouthful and then go back to his painting. It was called The Wave and it made a good stir in its time" (Guy de Maupassant, "La vie d'un paysagiste," Gil Blas, September 28, 1886; also see Hélène Toussaint, Gustave Courbet, 1819-1877, exh. cat., The Royal Academy, London, 1978, pp. 228-230).

Courbet’s instinctual understanding of the sea, so powerfully captured in paintings like La mer orageuse, has been recognized by artists from the Impressionists to Abstract Expressionists, many of whom were deeply influenced by his work. Édouard Manet named him “the Raphael of water. He knows all its movements, whether deep or shallow, at every time of day” (quoted in Charlotte Eyerman, "Courbet's Legacy in the Twentieth Century," Courbet and the Modern Landscape, exh. cat., 2006-2007, p. 103). Paul Cézanne was in awe of Courbet’s ability and named one of the artist’s waves as “one of the important creations of the century…. It hits you right in the stomach. You have to step back. The entire room feels the spray” (as quoted in Eyerman, p. 32). Nearly a century after Courbet left Étretat, in a review of Wildenstein Gallery’s Courbet retrospective in 1948-49, Clement Greenberg, a champion of abstract painting, lauded the artist’s paintings, notably his marines in which “[the subject the artist seems…] to have been able to handle best was inanimate and removed somewhat by physical distance— especially those things one is unable to take between one’s fingers, like light, water, and the sky. For all his adoration of the solidity of nature, Courbet came in the end to feel its intangibility with the most truth” (quoted in Eyerman, p. 22). Following Greenberg, critics and artists have continued to recognize the drama and physicality of Courbet’s seascapes, reappraising the waves for their parallels to the action painting of Jackson Pollack, the energetic painterliness of Franz Kline, and the atmospheric, textural methods of Gerhard Richter.

We would like to thank the Association des Amis de Gustave Courbet at the Institut Gustave Courbet, Ornans for kindly authenticating this work, which will be included in the forthcoming catalogue raisonné based on the work of Robert and Jean-Jacques Fernier.